Sikorsky Builds Big – the S-56

The large and powerful Sikorsky S-56 was Sikorsky’s answer to the U.S. Marine Corps’ request for a shipboard helicopter that could carry heavy loads on amphibious assaults.

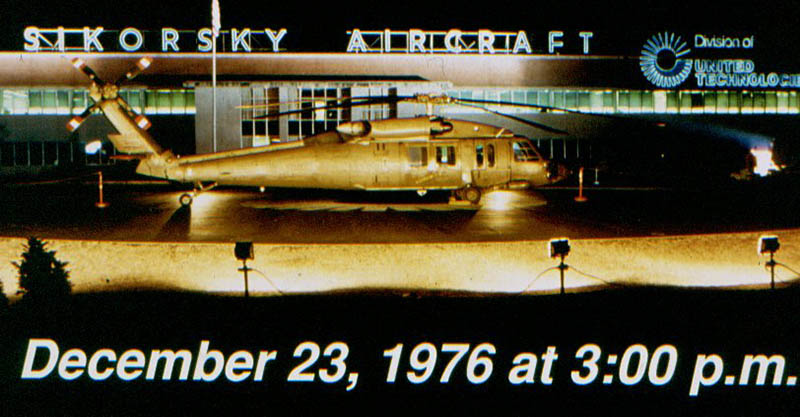

One of the key milestones in the history of Sikorsky was December 23, 1976, when we won the UTTAS program, the Utility Tactical Transport Aircraft System that became the BLACK HAWK. This win ultimately propelled the company to once again become the world’s leading helicopter company, a positon it continues to hold. We asked Bill to talk about some of the earlier days prior to UTTAS and the later days after he went on to become president and then worked up at UTC Corporate headquarters.

Winning the UTTAS competition was a make-or-break outcome. It was also a huge technical achievement. But the story of what management was doing, what contributions they made, who specifically made tipping point contributions, is a story I don’t think has been told. I’m going to try to do that. As you said, I had a front row seat to all of this and I also participated in it. My comments are simply recollections and my views as I saw it. They do not have the rigor of an historical document.

Let me go back to 1972, that’s a very pivotal year. We were developing our proposal for the UTTAS, against Bell, Boeing Vertol, and maybe Hughes. The first proposal would decide which two companies would be selected to compete against one another in a fly-before-you-buy, winner-take-all contract for production. Eventually Hughes did not bid.

The stakes were enormous for Sikorsky. Our production was declining rapidly and without this contract we could be out of military production in a few years. It was a do-or-die situation, a matter of survival. We had a contract to build the CH-53E, but that was on shaky ground. We were at 6000 employees, down from a peak of 12,000 and shrinking. This decline took place over a number of years and I’ll give you my views as to how this happened and why.

The facts are clear. By the end of the Korean war Sikorsky dominated the market in virtually all the services. In the Viet Nam war, the Army had developed a greater role in air mobility and went out to revamp their fleet of helicopters to meet the demanding requirements of that role.

To our astonishment we lost every one of those competitions, the UH-1 to Bell, the Chinook to Vertol and the Light Observation Helicopter (LOH) to Hughes. The devastating effects were self-evident; our competitors would take over our position in the market and the important Army mobility role was lost to us. Why we lost is not clear but the view on this was as follows. In the early years Sikorsky philosophy was clear, that we had the best technology and if we build it the customer will buy it. It worked. While we lost most competitions, surprising as it seems, Mr. Sikorsky and his team would build a prototype and show the customer that his concepts and technology were better. In most cases he was right and the government would turn around and give us a sole source, cost-plus-fixed-fee contract, with little or no financial risk. Now however, in the 60s, defense costs were soaring. The government’s response was to eliminate sole source contracts for both the development phase as well as production; a total procurement package, a high risk. Furthermore, Sikorsky’s competitors were maturing and becoming quite competitive. We were told that we were viewed by the Army as arrogant and not fully responsive. The criticism was that the company would propose what we thought the Army should have and not necessarily what the Army wanted. Also, it would appear that the new procurement process went down hard.

Internally, the blame for this was put on the disconnect and bickering between the engineering department and marketing. Whatever the reasons, we were out of the Army market and something had to be done.

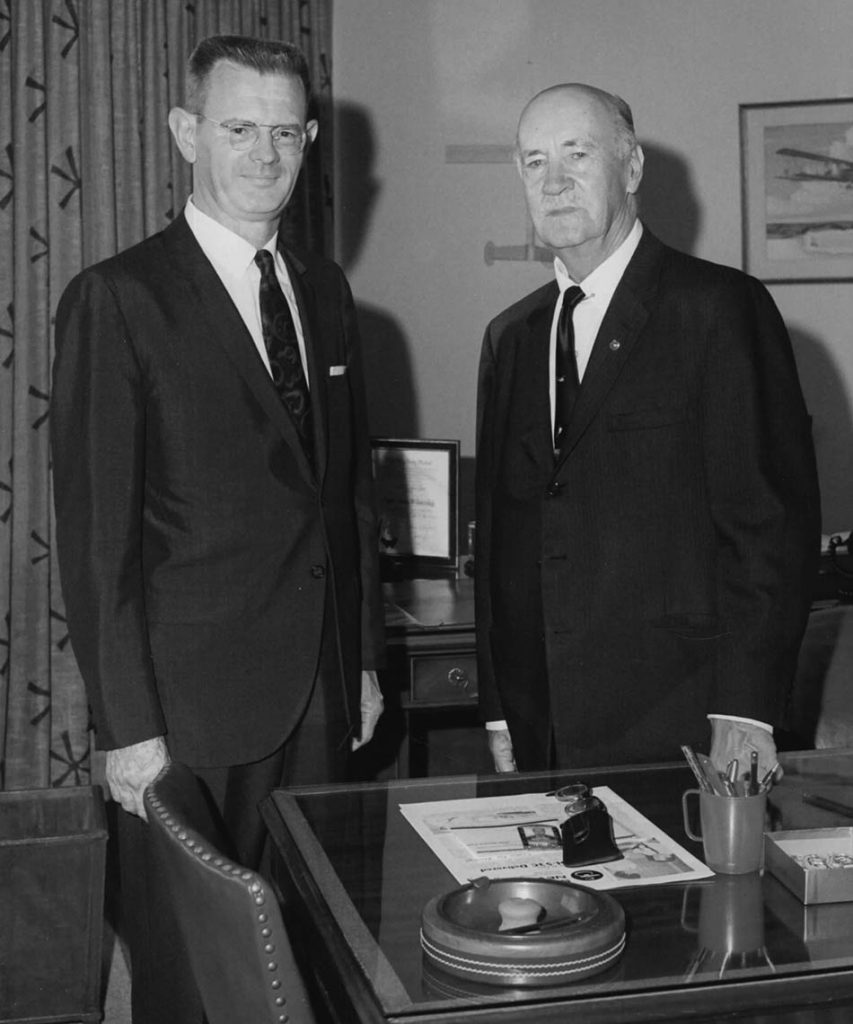

Lee Johnson, who was the president of Sikorsky, and Jack Horner, who was the CEO of United Aircraft had a brilliant idea. Their solution was to bring fixed-wing management into Sikorsky, bringing with them the modern expertise from Douglass Aircraft. They hired Carlos Wood to be our engineering manager, and Jim Clyne to be our marketing manager. These were two seasoned executives from Douglas, two guys who could work with each other, hopefully to solve the constant battles between marketing and engineering. I credit Carlos Wood with totally revamping the engineering department which would create the foundation which ultimately would help us a decade later to win the UTTAS competition. He was a game changer who got a hold of a lot of young engineers like myself and others like Ray Leoni, and put us into key positions, with broader responsibilities. He then sent us to an internal management school, where we developed a better sense of professionalism and organizational and business acumen. It also helped us bond, breaking down some of the stove pipes between departments. To improve our technology and the capabilities of the research team, he brought to Sikorsky the Scientific Advisory Committee that existed at United Aircraft. It was a group of renowned experts in the field, materials, aerodynamics, predominantly working with Pratt & Whitney and Hamilton Standard, and their role was to have these bi-annual reviews of technology issues and to not only review the technology, but also review the people who were doing that and to help them improve.

The new management would now be tested to see if the changes were in fact working. The Army put out two bids for competition. The AAFSS, the Advanced Aerial Fire Support System, which was a high-speed gunship helicopter with a wing and a pusher propeller and the HLH, the Heavy Lift Helicopter. Those were the two major competitions which would add a great deal of capability, and both would, in the Army’s view, require advanced technology to achieve. To our astonishment, we lost both competitions. The AAFSS loss to Lockheed was particularly hard to take, but in hindsight it was inevitable, and that loss in the end helped us learn a lot about what we had to do to get our act together. In fact, we won the UTTAS competition in large part because we learned our lessons and vowed, never again.

Lockheed had recognized that the Army was looking forward to new technology for its future helicopters, particularly in their rotor systems. Bell, Boeing and Lockheed were all participating with the Army using both company and Army funded research to develop concepts to greatly improve reliability and performance. Lockheed had come up with an attractive concept, a rigid rotor which would essentially eliminate the typical rotor system’s bearings, seals, and lubrication. Also, the plan was to use advanced materials to replace aluminum blades to provide better safety and performance. This concept continued to get not only Army funding but NASA support leading to a prototype test of a scaled down rotor system at NASA’s Ames Research Center, and a small test aircraft, the Lockheed XH-51.

Lockheed submitted that concept for the AFFAS and we, believing the rigid rotor would not work for that mission, submitted the only technology we had, the typical tried and true aluminum blades, with a hinged rotor consisting of bearings, seals and lubricant. Not surprisingly the Army selected their design. Internally the finger pointing was rampant and Carlos was taking the heat for it.

I have a somewhat different take. Yes, we should have developed more advanced technology and we should have been working hand in hand with the Army/NASA researchers. However, as it turned out, the Lockheed AFFAS contract was cancelled because as our guys suspected, the rigid rotor did not work at higher gross weight than was tested at NASA Ames and with the XH-51 test aircraft. The Boeing HLH didn’t work either and was cancelled. In the end, despite our mistakes and the bickering, their designs didn’t work and ours, we believed, would have; lots of lessons to be learned.

After the losses there was a big hole in our workload and in our morale. Carlos was looking for a project with new generation technology to fill the gap. George Howard in advanced design had come up with the ABC, Advancing Blade Concept, a counter rotating rigid rotor system with titanium blades. Carlos got the research funds to build a prototype and test it. The tests were successful.

For Carlos, the losses were too great and Lee Johnson asked him to leave. Years later, Carlos sent me a letter sharing his disappointment over what took place. How ironic it is that he would never know that his decision to launch the ABC with the titanium blade technology would help us win the UTTAS, and the ABC itself would be the concept Sikorsky would propose to replace the BLACK HAWK 50 years later.

It was decided to put Jack McKenna in charge of all Sikorsky helicopter operations. He would have full responsibility and authority for the upcoming UH-1 replacement program, the UTTAS. Jack was a hard charging, bright, no nonsense guy. He was the transformative figure needed, and he did just that.

One of the first actions he made was to name Harry Jensen as Engineering VP. Harry was a brilliant, wise and tough manager. He was often overlooked for the engineering top spot. He knew where all the skeletons were buried and who the right guys should be to win the upcoming competition. Jack had developed a great relationship with Harry and knew that he was the best guy for the job. How right he was. Harry and Jack turned the engineering department into a strong cohesive unit and some of the top managers were asked to leave. The stovepipes between departments were gone. Jack met with Army management to let them know that the new Sikorsky would be a responsive, innovative Army teammate. He was a big man who brought an infusion of energy to us all.

With Jack and Harry in position, UAC decided on one final change they hoped would assist them in developing the advanced technology we would need to meet the demanding requirements of the UTTAS. They decided to bring down from corporate, the head of its Research Center, Wes Kurht, as President of Sikorsky. Who better! Wes, Jack and Harry were a perfect team. Wes knew the lessons from the Lockheed loss and the Army history. He also knew that it would take an overhaul of our technology and a better relationship with the Army’s technical guys. In one of his first acts, Wes met with engineering management and gave them marching orders to work closely with the Army research team, share our proposed research with them and participate in their funded research programs. His admonition was that when the Army technical evaluators review our proposal, they should not only be fully aware and familiar with our technology but also be comfortable with the credibility of Sikorsky’s technical team and its ability to do what we propose.

Wes also had a concern as to whether we could ever win the UTTAS given that we were viewed as a Navy contractor and our competitors were deeply involved as key Army contractors. He had a heart-to-heart talk with the Army and came away encouraged that we would be given a fair shake. He also was concerned that the Army could be looking for as advanced concept. So he decided to have an internal competition between the single rotor concept and the ABC using two teams to determine the best design for the UTTAS.

Ray Leoni of the Advanced Design Branch had been working with the Army on LUH, (Light Utility Helicopter) designs which would replace the UH-1. He would lead the single rotor team and Ray Donovan would design an ABC version. As we expected, the single rotor concept won. The ABC concept was too high risk at that time and we were well along in developing single rotor technology. Having made the decision to go ahead with the single rotor design, Harry Jensen gave Ray Leoni the position of the UTTAS engineering manager. Ray would go on to be the UTTAS program manager.

In 1969 I was head of Structural Mechanics, involving vibrations, aeroelastics and structures. Harry asked me to instead take over the rotor design group and lead the company’s development of an advanced rotor system for the UTTAS. Recognizing that new materials and aerodynamics would be imperative, he also gave me the responsibility to manage and direct all the research being done within the engineering department to assure that they are focused on the design we come up with. Bob Zincone was a structures engineer and someone who I knew had much more potential. In my view he was one of the brightest engineers in the company. He became my sidekick and in the following years Bob succeeded me in every position at Sikorsky.

We were in a catch up mode. Our competitors had been working with the Army for years on advanced rotor technology. It was 1970 and we had 2 years to design, develop and demonstrate our advanced rotor. We selected an elastomeric bearingless rotor, high twist blade with a titanium spar with a graphite composite cover and a unique swept tip. For the tail rotor, we proposed a cross beam fully composite rigid rotor.

With regard to the main rotor blade spar, we were fortunate to have the ABC titanium spar technology as a foundation for our proposed titanium spar. We wanted to use a composite spar but concluded that we didn’t have the confidence to use it, particularly with the time constraint we had. As it turned out we had to start from scratch to even develop the composite cover.

We now had what we believed would meet Ray’s design requirements. With the Navy’s help we demonstrated successfully the new elastomeric rotor technology on the CH53D, a major accomplishment in a short period of time.

In 1972 I had become Chief of Design and Development. The Army’s request for proposal was in and shortly after we sent in our proposal and held our breaths. It was an amazing moment within the company when we learned that we and Boeing were selected to be the two companies to compete in a fly-before-you buy, winner-take-all, competition. Each of us would design, build an deliver 3 prototypes to the Army at Edwards Air Force Base where Army pilots, maintenance and logistics teams would evaluate both, side by side.

Fast forward to 1974. The prototypes were built and we began our flight tests. Right from the beginning we encountered a series of problems. I refer you to Ray Leoni’s book, Black Hawk, the Story of a World Class Helicopter, which details the history of that period of time. It had been a long time since we had designed a new helicopter and it showed. At this time I was Chief Engineer and Bob Zincone took my place as Chief of Design. It was our team’s responsibility to fix the problems. The problems were so serious that doubts of our design and our ability to solve them were there, within the company, and within the Army.

United Aircraft decided, for a number of reasons, that the corporation needed to diversify and hired Harry Gray to be its CEO and Chairman. It was a decision which would ultimately transform the company into the powerhouse United Technologies Corporation which would include Otis, Carrier, Aerospace, as well as Pratt & Whitney, Hamilton Standard and Sikorsky. Harry was unbelievably helpful to Sikorsky and his constant support of the BLACK HAWK and to the team was instrumental in our success.

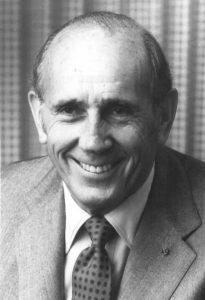

It didn’t take long for Harry Gray to realize that to win we needed to submit not only a winning design but also a winning manufacturing and business plan, and we needed a businessman to make it all happen. Gerry Tobias, who had a long and successful history with Boeing, was chosen as President of Sikorsky replacing Wes Kurht. Wes had been the right man to help us win the first phase of the competition and now he was needed back at corporate as Chief Scientist. Gerry was not only a businessman but also a promoter. He instilled in us the importance of marketing and integrated the engineering and marketing functions into a very cohesive team. He spent a lot of time with me and Bob Daniell, who was in marketing and the Programs VP, teaching us and mentoring us. He brought in a new manufacturing team including Gene Buckley, who will be discussed later, to build a manufacturing plan for the UTTAS.

The technical problems were now at a point where Harry Gray scheduled a meeting at Sikorsky to review the issues. We were worried and more than a bit tense. We didn’t know what to expect and we were already drained by the intensity of round the clock efforts. Besides, the Boeing team was flying their prototype on Long Island, in plain view, and didn’t seem to have the same problems. Harry came into a crowded room. Gerry turned the meeting over to Ray who gave an overview of the issues and then turned to me. I was Chief Engineer so I had the ultimate responsibility to solve these problems. As I began, Harry stopped me and said “I’m not interested in problems. Just tell me what it takes to fix them and what I can do to help.” He did just that throughout the program. It was a tipping point for us. His confidence in us was what we needed.

The biggest problems we had were difficulty in achieving our 3g maneuvering capability, and high vibration and performance shortfalls, all show stoppers. It was at this point that Evan Fradenberg, from the Aerodynamics Research Group, and Hank Velkoff, a retired Air Force helicopter expert, came to my office and told Bob Zincone an me the astonishing news that the cause of the problems was that the rotor was too low and had to be raised. They concluded that the rotor blades were so close to the fuselage that it created rotor interference. In short the rotor needed to be raised. Evan, Hank and his team had a lot of credibility and we agreed to take it upstairs. This created a big problem for us because the lower rotor was essential to allow the helicopter to be air transportable, a must. Everyone can visualize why the rotor must be low and very few can easily buy the technical analysis. We briefed Al Poole, head of marketing, and Bob Torok, head of programs. Both fell off their chairs and said hell no.

We took it to Gerry Tobias’ office. He wasn’t an engineer, and for me that was an advantage. He and I worked well together with complementary skills and mutual respect. I had credibility and although he would prefer not to raise the rotor, he sensed that this could be a make or break decision and he had to go along with our recommendations. He needed Harry Gray’s approval. Harry once again would support us, and he wanted assurances that we could come up with the best solution we could to achieve air transportability. Don Ferris, an amazing rotor designer found a simple solution of using a bolt-on rotor shaft extender, which could be removed and stored during air transport. Boeing would have the advantage here, but we discovered later that they too had the rotor interference problem but didn’t raise the rotor because of the importance of air transportability. This was a pivotal moment. The aero guys were right on and the vibration, speed and maneuvering problems were resolved. Boeing did not raise their rotor. To the Army the raised rotor issue was a major discriminator. We did it and they didn’t. On December 23, 1976, we were informed that we had won the UTTAS contract. We had a hell of a celebration.

Now we had to produce the BLACK HAWK and this was to be enormously challenging. We had not been in production for many years and this helicopter had new technology, never produced before. To compound the issue, we were also in production for the Seahawk, CH-53E and the new commercial S-76 which Gerry Tobias initiated. All departments were stretched.

Gene had been hired by Gerry given his manufacturing experience. He managed the industrial engineering and manufacturing engineering plan for the UTTAS program. Gerry made him manufacturing VP. The problems were serious and myriad. Purchasing, production control, manufacturing engineering and the factory all had problems and we weren’t delivering helicopters. The customers were unhappy and talks of higher costs and delays were threatening the program. We had grown back to 12,000 employees. Gerry continued to bring in new production management and that hurt rather than helped.

Bob Daniell was a long time Sikorsky employee who rose through the ranks in the marketing and program areas. Bob and I grew up together within the company. We were a perfect blend of engineering, programs, and marketing, a long time team. Bob had an extraordinary leadership ability. Under Gerry Tobias, he had become the company’s executive vice president and was the logical choice to return company management to the internal folks, restructure the team, increase the morale and get customer confidence back. That’s exactly what he did. I was named EVP and Chief Operating Officer, Bob Zincone became VP Engineering and Gene Buckley was VP of Manufacturing. We set up operations centers which we visited every day to help them solve the interdisciplinary issues. We had pizza and cake parties to recognize operations accomplishments, and little by little we began to turn the ship around. We called our employees the “Sikorsky Family”.

In the 1980’s Sikorsky was in production of the BLACK HAWK, Seahawk, CH-53E’s, S-76’s and S-92’s. We had surpassed $1B In sales and were profitable. We were, once again, the world’s leading helicopter company, a position we hold to this day. While this presentation discusses the role of management, we owe our success also to a number of key contributors. The list is too long but I would like to recognize some key contributors, particularly Ken Rosen, Lou Cotton and Ray Leoni’s whole program team. All were indispensable to us. We must also recognize Charlie Crawford of the Army. Charlie was the senior Army technical person and was a major contributor to the success of the program. He was uncompromising in holding us to meeting the technical requirements, but was always ready to help us solve our issues to get the Army the best final aircraft design.

We can be most proud that the BLACK HAWK continues to serve the men and women of the Army with distinction for over forty years and continues to do so for the foreseeable future.

I had the unique experience, indeed the privilege, to be mentored by so many people, particularly those mentioned in this presentation. It is also clear that we all were very lucky to be in the right place, at the right time, to participate in the most important, demanding and transformative period.

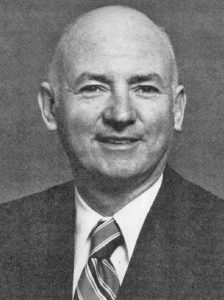

I want to single out Harry Jensen, who was like a father to me. He decided to take a big chance on me. I was just about 30 and Harry was a wise old man in his later business years. He took me under his wing and taught, coached and nurtured me throughout that period. He paved the way for me to move up the chain of command. At the executive meeting announcing my replacing him, he was sitting next to me and in classic Harry father and son way, he reached over and put a Maalox antacid into my hand.

He had a personal hand in the development of other young engineering people in becoming Sikorsky leaders. When he died he left instructions regarding the men whom he wanted to be among his pall bearers. They were “his boys” as he called them. They were Bob Daniell, Bill Paul, Bob Zincone and Ray Leoni. It was a great honor for us.”

I was inspired to present these recollections because I wanted the record to show the contributions of these men.

I also want to thank Art Linden, retired leader of the LHX/Comanche program, for asking me to do this and his tirless work on its behalf.

The large and powerful Sikorsky S-56 was Sikorsky’s answer to the U.S. Marine Corps’ request for a shipboard helicopter that could carry heavy loads on amphibious assaults.

The first flight of Sikorsky Aircraft’s Black Hawk occurred 50 years ago, on October 17, 1974. Since then, over 5000 Black Hawks have been delivered to customers, making it Sikorsky’s longest production program.

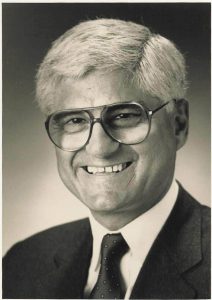

Former Sikorsky President Bill Paul reflects on his career with Sikorsky, meeting Igor Sikorsky, and the Sikorsky Aircraft Company’s 100th anniversary.

Bill Paul recollects one of the key milestones of Sikorsky history, the win of the UTTAS program that became the Black Hawk helicopter.

Late in the afternoon on December 23, 1976, Sikorsky received a telephone call that will likely rank as the most important call in its 90 year history.