Personal Recollections

Bill Paul: Reflections on Sikorsky’s 100th Anniversary

by Bill Paul

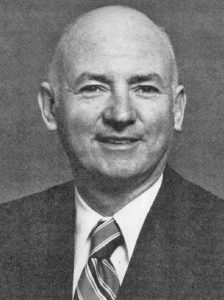

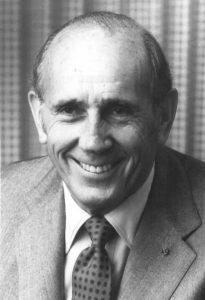

Bill Paul joined Sikorsky when he was 19 as a blueprint machine operator. After his first year of engineering night school he became an engineering aide. From that point forward, Bill progressed rapidly and held a number of engineering management positions from Chief of Rotor Systems in 1969, to Vice President of Engineering in 1975. He later became Sikorsky’s President and went on to United Technologies as Senior Vice President Defense and Space and retired in 1997 as UTC Executive Vice President and Chairman of International Operations. In this article, Bill reflects on his career with Sikorsky, meeting Igor Sikorsky, and the Sikorsky Aircraft Company’s 100th anniversary.

Let me begin first by giving you my background. I was born in Bridgeport, in fact the only Sikorsky president who was born in this area. In my era, we didn’t go to college. A high school education was just perfect. I was heading for a high school education, then I met my wife Gloria in high school and she changed my whole outlook.

We decided that I would go to Bridgeport Engineering Institute. I went nights. I also looked for a job at Sikorsky and I went to South Avenue. It turns out that the only job I could get was being a blueprint machine operator, but I decided to take it. I joined Sikorsky in 1955 while going to school part-time nights, continuing my education.

I grew within the company in its engineering department. In 1965 I was running an organization of 20 to 30 engineers. By the time we got to the Black Hawk competition, I was doing design work on rotor systems. Then I became vice president of engineering. When we got into the factory and had problems with manufacturing, I ended up being chief operating officer, running engineering and manufacturing operations.

Then a few years later, I became president of the company, and then a few years after that, I got promoted to go to the corporation and became a senior vice president of United Technologies in charge of defense and space systems. It was a situation where I was able to see the company at the very beginning, come through that whole process. It was a great learning experience.

Oh, by the way, I am still married to Gloria for 67 years so I gave her a lot of credit for that.

Starting His Career at Sikorsky Aircraft

As I started in the blueprint department. I was also delivering supplies to the engineering department. At school one of the instructors worked at Sikorsky, and he said, “We don’t have any engineering aids within the company, and it’d be great if you can come and help us because we’re just a bunch of engineers.”

I got a transfer from the blueprint department to become an engineering aid. They gave me a job basically measuring vibration levels in all of the Sikorsky helicopters that were being delivered. Those helicopters had a lot of vibration problems so each one had to be measured to be sure they passed a certain level before they could be delivered. I flew every one of those. I did that for a few years, and then gradually I started to get involved with solving those vibration problems. and that’s where people began to see what I could do. That area was very important to me in my own education and also to my visibility within the company. They began to believe I was a guy who could get things done.

This whole career, when you look at what I just said, immigrant son comes in, starts at the bottom, goes to the top, that’s something that is a lot more rare today than it was then. People who were in key positions were looking for people who could solve these problems, so when they saw somebody who was young, they were able to reach down and nurture them. In my life at Sikorsky I’ve had three people who really were key to my getting ahead: Wes Kuhrt, Jack McKenna, and Harry Jensen. there’s no question about it.

Meeting Igor Sikorsky

First of all, there’s a funny story here. It’s actually a prophetic story. Within the first few months that I joined Sikorsky, I was taking a course in drafting at the Bridgeport Engineering Institute and the question in my mind was, What would be the best studies to go through to help me move up at Sikorsky? One Saturday morning I was walking into the lobby of the Bridgeport plant, and who do I see? Well, Mr. Sikorsky. His back is to me, he was looking up at the clock and setting his watch as he always did.

I summon up the courage to tap him on the shoulder. He turned around and I said, “My name is Bill Paul. I just started going to school nights. Mr. Sikorsky, I’d like to understand, what would be the best subjects to study?” He spent about ten minutes with me talking about structures and dynamics and things of this nature and then we shook hands. Now, the thing that blew my mind downstream was how in the world would those two people, Mr. Sikorsky, the founder, and this young kid who has just started giving out supplies, how would he possibly know that someday I would run his engineering department and then run his whole company? Ain’t that an amazing story in a way?

Now there’s another one, when Mr. Sikorsky would come in to some meetings we would have, like presentations which were being made, and he would always sit in the back. Everybody would always get up and force him to a front seat. The whole humility of the man was extraordinary.

Flight Testing the S-60 Skycrane with Igor Sikorsky

There’s another story of Mr. Sikorsky during this process when I was taking measurements of vibrations on the S-60 flying crane. Mr. Sikorsky’s thrust in life was to save lives and so he came up with the concept of the crane helicopter. This was after he had retired, but he was still there working as a consultant. He came up with the idea that he wanted to have a flying crane. What this is, it’s a cockpit attached to a beam that has a main and tail rotor on it, but nothing underneath, no fuselage, no cabin.

The idea was to be able to attach whatever cabin you want underneath that, for whatever issue, whatever problem you might have. We also had a rear looking cockpit so if you want to use the hook to lift something up to the top of a building, the rear-facing pilot could see that very well.

But what Mr. Sikorsky really wanted was an air ambulance capability. He wanted to have what he called a people pod that could sit underneath the helicopter and you could take it to an accident site or to a fire site or whatever the emergencies might be, and have a mini operating room inside this people pod.

At that time I was measuring vibration. I got a call from the program manager and he said, ”We want you to fly on this flying crane.” Mr. Sikorsky would like to see what it’s like to be on a platform underneath the crane. What the guys did was they built a platform with cables hooked up to the fuselage. They mounted four chairs, and Igor Sikorsky was there, as was Michael Gluhareff, the person who inherited his job and was running engineering, his old comrade, the program manager, and myself, and I had this vibration stuff, I was measuring vibrations.

We took off. Now here we are in the breeze about a thousand feet up. I was like about 22 years old, and I was rather awestruck with him and also awestruck at the fact that we had a platform. I was out there in the breeze by myself. Mr. Sikorsky gets up, and everybody said, “Don’t get up, Mr. Sikorsky.” He gets up, he starts looking around with his handkerchief, walking around with the vibration and stuff, and everybody was a little petrified. Then he decided to come sit back down.

Then he said, “What I want to do is I want to get a people pod made out of plywood, but before we do, I need to get this vibration lower.” He turned to me and asked if I could make this vibration level lower. Well, I said there’s one way of doing it. He’s quick, “I’m talking about this afternoon”. This gentleman was very determined. I took a tube and two plates, and had them welded together so I had four tubes. I put bungee cords around these tubes, tied the ends together, put them in a test rig to be sure they could hold, and then we hooked up the whole platform to the helicopter, with it only being held up by bungee cords. The four of us were on bungee cords and flying again.

The vibration level went down. It was terrific. He said, “Okay, now what I want to do is I want to go back overnight and build the little people pod and hook up everything to that.” He wanted this kind of a mini ambulance. What happened next was we took off, again with the four chairs were mounted. We got up in the air and the vibration of the floor was doing this. All four chairs were doing this. [Shaking his hands up and down at a fast rate]. I pointed out to Mr. Gluhareff, “We got to get him down.” He said, “No, no, he won’t change.” He kept on going for 30 minutes, no matter what happened. He wanted to see it, he wanted to feel it. Then we landed. After we landed, I looked underneath, and they forgot to install the crossbeams under the seats. We were sitting on four chairs on plywood tacked only to the ends.

How’s that for a story? That was the way it was, it was – informality. If we wanted to get it done, he wanted to get it done, it was going to be done overnight. In a rush of doing things, these things do happen. It certainly wasn’t the formality that you see today at the company.

The Black Hawk Program Win

In 1972 the Army issued the request for proposal for the UTTAS. At that time there were four major helicopter companies. There was Boeing, Bell, Hughes and ourselves. For all of us, it was a must-win, but for Sikorsky it was a make-or-break situation because we were slowly going out of business. The CH-53D production was gone, the S-61s were gone. We had no commercial aircraft at the time. On the horizon we had CH-53 Echoes coming down the line but that was too small a program to sustain Sikorsky as we knew it. We were now a onesie-twosie shop. We became, at that point, almost a mod shop, a shop of overhaul and repair.

What had happened? The great Sikorsky was not in a favorable position? It was because of our history with the Army. We had lost every single competition that the Army had in the 1960s for the Vietnam War. We lost the utility helicopter to Bell. That was the Bell Huey. We lost the Chinook heavy-lift helicopter, it was right in our wheelhouse, to Boeing Vertol. We lost the small scout helicopter to Hughes. It became the OH-6.

If that wasn’t bad enough, a few years later, the Army came up wanting a high-speed helicopter, the AAFSS – the Advance Aerial Fire Support System. It was a helicopter that would go like 220 knots, and we have a wing and single-rotor helicopter again, right in our wheelhouse. We lost that helicopter program to Lockheed, a company at that time that had never built a production helicopter. The reason why Lockheed won was because they had come up with a rotor system concept that was a rigid rotor, no bearings, no lubricants, no seals, and it was designed by Lockheed, but also supported by the United States Army. The Army loved it. It was almost like it was not only Lockheed’s rotor system, it was the Army’s rotor system.

When the competition came up and we proposed our helicopter, we had the 1945, 1955, 1960 concept of a flapping rotor with bearings, with dampers, with lubricants, aluminum rotor blades, and so on and so forth that frankly, they didn’t want. Sikorsky was viewed by many as blacksmiths because we had proven technology that worked and we were reluctant to change.

We learned two lessons there. We didn’t have the technology, and also we were supporting our technology internally and we were not responding to the customers so that, in fact, our technology never became their technology. Those two lessons were the lessons we learned going forward.

The company was now hanging on the ability to have the technology necessary to win the UTTAS competition, and we were behind. We were the underdogs We had two years to get this thing done, and we didn’t have a moment to spare.

First, the corporation had to decide if we were even capable of winning this UTTAS competition? Or, were we a company that was never going to win an Army contract? In their wisdom, the leaders of United Aircraft decided that they had to fix this company and they picked their chief of research and technology at the corporation, Wes Kuhrt, to come down as our president.

One of the things Wes had to do was to go to the Army and convince himself that in fact, we had a chance of winning this, given the history I just talked about. As a result of that, the Army gave him those assurances that we would not be judged on our past experience, we would just be judged by what we do now.

At Sikorsky Wes met Jack McKenna, who was really a hard-charging operating guy, and they picked Harry Jensen as their engineering manager. Harry Jensen was a guy approaching 60 years old, a strong, tough guy, but he knew everything that was going on with the engineering department and could lead it.

Those three guys basically transformed the company into a company that would be in a position to win the UTTAS competition. By 1970, this is a couple of years later, they had worked with the Army to let them know they really wanted this program. We weren’t sure we could win it. More likely than not, Bell and Boeing, who are Army contractors, would probably win, but Sikorsky decided to invest their own money in 1970 and get ready for the competition that would take place in 1972. That’s where I came in because what they were looking for was new technology. I had been in the technical area at this time. I was not in the design area.

Harry Jensen brought me in. He was the man who became my mentor and my father figure. He was the one who said, “Okay, Bill, you’ve got to develop this technology. You don’t have to be encumbered by what took place in the past.” At that point, he wanted a young guy. He wanted someone who was fresh, who could take a fresh look and not be involved with what might have been wrong in the past. Then I went out and found probably the smartest engineer I could find. His name was Bob Zincone and he became my sidekick.

He was my sidekick throughout the entire rest of this process. when I was the president, he was the vice president. After I was president he became president. Bob Zincone and I– well, I was no longer ”I”, it was “we” at that point.

Back in 1968 Wes recognized that the rotor system was a big part of this whole issue with Lockheed, and so he set up a design competition of two different designs within the company to see which one would win. One of those was a conventional design, what you see today as the Black Hawk helicopter. The other was a design using the ABC, the XH-59A Advancing Blade Concept.

The reason for looking at the ABC was because the Army was so enamored with the Lockheed program which was a rigid rotor, that we wanted to see if a rigid rotor helicopter at that time could also be a contender. It certainly would be a great advancement. We had these two helicopter designs. We set up a group of us to evaluate them, and we concluded that we could not go with the ABC at the time. It would just be too big a stretch. It was the conventional helicopter design that you see today, modified across 50 years, that we proposed for the UTTAS.

When Harry Jensen selected me to do the technology for the UTTAS, he also selected Ray Leoni to be the program engineering manager. Harry took all the engineers and he put them under Ray in a place just for the UTTAS, and Ray would be responsible for the day-to-day activities of that group.. At the end, Ray put together the proposal which was rock solid to win this competition, and so he ended up also becoming program manager at some part in this competition. He played a very important role. Ray and I tend to say to each other, he was the designer and I was the technologist.

Ray ended up being a strong leader of this organization. He would take no prisoners as it related to meeting the requirements that the Army set up.

Looking back, my philosophy has always been that it’s good to be a little naive and enthusiastic. I think to be naive, you have to be young. I was 33, 34 years old, and I didn’t know what I didn’t know. All I knew was we had a task to perform and we had to get it done. A certain amount of naiveté and enthusiasm was exactly what was needed and I had that at the time. If I had known then the things we would have to do to get this thing done, and the risks we would have had to take, and that we’re putting the company on the line at this point, I’m not sure I could have done it. At the time I didn’t think that way and neither did Bob Zincone. We were just obsessed with the goal involved, which was to develop the technology of the rotor system, which is probably the heart of our problems, the heart of what it would take to win, along with others who were developing the other technologies that were necessary in terms of the reliability and things of this nature, crashworthiness. Anyway, that was the feeling I had at the beginning.

The Army actually had two requests for proposals. One was for the utility helicopter; another one was for the attack helicopter. Now, the attack helicopter was probably going to be won by Hughes. We had to compete with Bell and Boeing for the utility, and the utility was the real core and biggest program because it could be used for a variety of missions. The Air Force, the Navy, and so on and so forth, and we knew this.

In August 1972 the decision was made. Surprisingly Bell was out. Sikorsky and Boeing were selected to design prototype UTTAS aircraft for a competitive fly-off. If you asked me back at the time how I felt, I would tell you that while we were euphoric, we were concerned about the next phases. We just couldn’t stop, each phase continued on. Now looking back over fifty years it’s awesome to see what took place. We’ve now built 5,000 Hawks. I don’t think we ever had an appreciation for how long this program would last and how widespread it would be. There have been thousands and thousands of U.S. and Allied troops who have flown Black Hawks under some of the most difficult and dangerous circumstances.

Ray Leoni’s contributions were immeasurable [during the UTTAS competition]. Part of that was not just the rotor system but also the crashworthiness. For example, they designed helicopters such that it had certain structural features. Like in a crash the cabin doesn’t close so if you’re inside you still have a cavity in which you can survive.

In addition to that, the fuel tanks are crashworthy. They’re made of rubber, but they also have the valves that break away and close so you don’t have fuel being spilled. The structure of the shafts and others were designed to be strong so that a bullet would not take them out. We have things like reliability features and so on, and Ray Leoni is managing all of that during this process. Combined, this entire team put together exactly what the customer wanted.

The week after we had won the UTTAS competition, we rolled out the S-76 helicopter. The S-76 helicopter was the creation of the new president we had, Gerry Tobias, who wanted to be in the commercial market, with the best commercial helicopter for that market.

Solving Black Hawk Design Challenges

I’ll point out that [during the UTTAS competition] we had a lot of problems, particularly in the flight test phase. In 1974 I had become chief of design and development. We had built the helicopters, we’ve built three prototypes, and we started flying them. Immediately we had problems, typical problems and some not so typical. The team pulled together and we solved most of these problems, but by early 1975 we had a really serious problem. We couldn’t meet our in-flight performance and maneuverability requirements and we had high vibration levels. It was so serious that the chairman of United Technologies came down to evaluate what was going on. We were a little bit concerned. Our knees had buckled, and we weren’t sure we could really solve some of these problems.

What he did for us was very pivotal. Instead of our going through all the problems with him, and we had plenty, he said, “I don’t want to hear your problems. I just want to hear your solutions. I want to hear you tell me what I can do to help solve them.” That night Ray and I and a team of people came back with a smile on our face, and we were ready to go back to work and solve these problems.

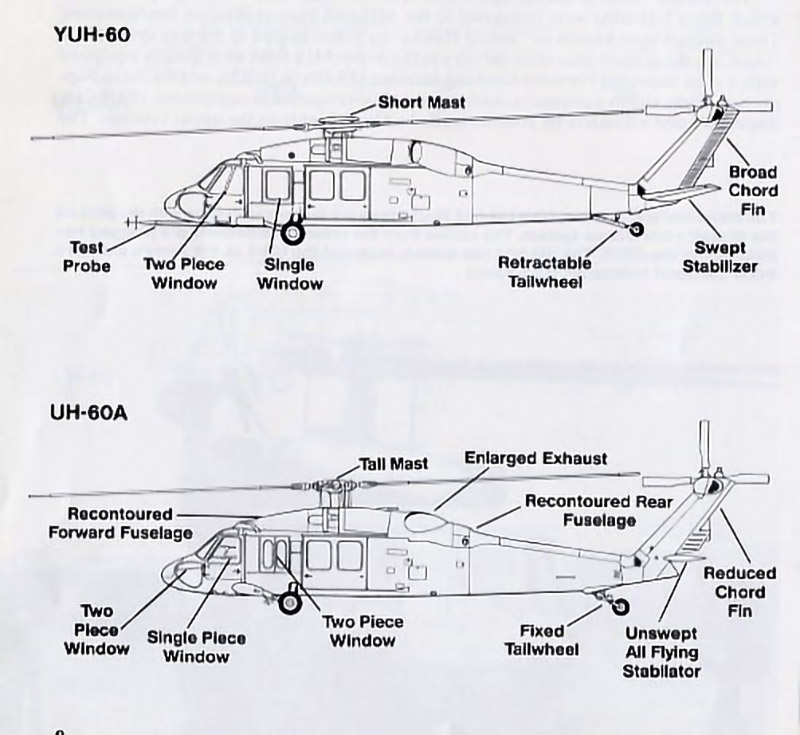

Now, it turns out that this particular problem, the maneuverability and the vibration, was caused by the fact that the rotor system was close to the fuselage, so that it could fit inside an Air Force C-130 to be air transportable. This closeness to the fuselage created aerodynamic interference, and that interference was causing the maneuverability problems and exacerbating the vibration problems.

We needed to raise the rotor but, of course, we also had to make it air transportable. We designed an extender on the shaft, and that that would raise the rotor. When it came time for air transportability, we would take the extender off and slide the rotor down.

Now, the problem with that was that our competitor Boeing had not raised their rotor. The question was, Are we sure that we really have to do this because we’re going to be gigged by the customer for being less air transportable?

Let’s talk a little bit about the process of solving that technical problem.

The culture within the company made it easy for us to solve our problems. We were guys that looked at the brutal facts, looked at them, solve them, and went on. We had the credibility with each other, we had the camaraderie with each other, and we’ve worked together for years. When it came to this particular issue, a fellow by the name of Evan Fradenberg who ran the aerodynamics section and Bob Zincone came into my office and Evan said, “You better sit down. The problem we have with the vibration and the maneuverability is caused by the rotor system being too close to the fuselage.” We went over all the details. What we had is that he had the credibility of aerodynamics behind him. It made sense to us. Now, the issue was that we had to take it to the program managers and the head of marketing. Their reaction, of course, was to fall off their chairs because you have something very obvious and that could be air transportability, how do I know that the vibration problem and also the maneuverability problems are going to be solved? All they had was our credibility.

I had to take this farther up the line to the president of the company, who at that time was Gerry Tobias, and he had me take it up to Harry Gray, who was the chairman of the corporation. It was that important. I think they had no choice, but I also think in the end, the credibility that we had established with Harry Gray was the difference in making that decision.

That’s how we proceeded on, not knowing still whether Boeing was going to raise their rotor or not, whether they had the problem or not. It could very well be that Boeing with the big Boeing company behind them had found another solution.

We were quite concerned that during the evaluation, this may be a loser. When it came down to it, we had no choice. This decision that we had to make was a make-or-break decision for the company because had we not done it, we would clearly not win.

Back when we had built our rotor system, we had it on the whirl stand where you test it, you tie it down. I got a call some time, it was a Saturday night about ten o’clock at night, saying there was some problem on the whirl stand so I got in my car and went over. 10 minutes later, I see Ray Leoni show up. 20 minutes later from Stamford I see Bob Zincone show up, Ken Rosen shows up, all these guys show up. We must have had 15 people in the room on a Saturday night. That’s the camaraderie we had at that time.

In March of 1976, we delivered our three prototypes to the Army and so did Boeing. The Army then had their flight test people going between two aircraft. This was done for nine months and they made their decision in December. We were told we won the competition. Then a few months later, the secretary of the Army came down and told us that we had a rock-solid proposal, that we might have still won this competition if we hadn’t raised the rotor, but it would have been very close. The fact of the matter is Boeing had never raised their rotor and we had. They applauded that courage to do so despite the fact that it would affect the air transportability.

Starting Up the Black Hawk Production Line

After we won the UTTAS competition, the big problem was we had to design a production helicopter, and we had to come up with production processes. That was probably as big a challenge, if not more, than the whole process of developing the helicopter itself. The company, as I said, had four years of stagnancy. We had to build the factory from scratch – the ability, the paperwork, the procedures, the processes, the people. We ended up hiring 6,000 more people, and we had to assimilate those people into the company.

At that point, we had changed presidents again. Bob Daniell had become president and I had become chief operating officer, taking over operations and engineering. We put together a team under Gene Buckley, a brilliant manufacturing engineer, to put together and solve these problems, and we supported him. What he built in that period of time was a company, a manufacturing facility you see today which was second to none in the industry. By the time I became president in 1982/83, we were delivering ten Black Hawks a month, three Seahawks a month, ten S-76s a month, and two CH-53 Echos a month. We were in full production, we were the leader in our business, and we had finally become the leading helicopter company in the world.

In my capacity as the president of the company, and even while I was in the design and engineering departments, I had a chance to meet and talk to a lot of customers. If you were a colonel running a program, let’s say like the Black Hawk or even other programs within the Black Hawk, what you’re looking for is the person that you’re dealing with having credibility. The word credibility was so important to me and to virtually everybody who dealt with them. We were honest. We faced up to our facts. We would say, I don’t know. We would do things, “I’m sorry, we made a mistake.” We did. We made plenty of mistakes, but when we told them what we told them, they believed us, and they felt that we could operate as a team together. I go back again to being of Italian heritage, it was very natural for me to do that.

There were Army people like Charlie Crawford and his team who held our feet to the fire, forced us to be the best we could be. Forced us to stretch, and continued to whack us over the head when we weren’t meeting all the requirements, which first resulted in a rock solid proposal that would win under any circumstances, and then a rock solid customer product that you now see over the last 50 years. To see this in the hands of so many different people gives us a feeling of the privilege we had in being a part of this.

The first time I went to an Army base right after we won, it hit me that we hadn’t just won the competition. We had created the finest helicopter that the Army could possibly have. When I saw those men and women crawling over the aircraft, I had tears on my eyes. We provided them with the capability to perform a mission and then get back home safely. Those are the things that make me, even today, emotional about what we did.

Reflections on His Sikorsky Career

I want to speak to everybody who contributed to this Black Hawk program, people who are still alive and those that are not. There was an intense pride because the Army had a product that was the best it can be, and the people who flew it would come home safely. In addition to that, in our local areas, we were able to provide jobs and prosperity for not only those people in our own area, but all the suppliers as well.

Bridgeport in the days of yore was filled with 100,000 people, and there was a major industry in everything. Bridgeport back in the time of the Industrial Revolution, the 1800s and 1900s, ended up being one of the leading manufacturing cities in the world. Bridgeport had Bridgeport Brass, Singer sewing machine, Underwood, and others. It had everything.

Sikorsky is the one company that has remained.

As I look back over these 100 years what was a constant throughout was the image that Igor Sikorsky always conveyed, and that is, his role in developing the products was really to save lives and improve the way in which people perform their missions, particularly in the military. Throughout these 100 years, that’s been a constant.

Sikorsky has a particularly outstanding reputation. Many of the customers would say, “We were flying a Sikorsky.” You didn’t hear they’re flying a U.S. helicopter. You didn’t hear it was flying a Bridgeport helicopter. It was a Sikorsky helicopter.

Everybody who has been in a position of management, or whether they’ve been in the machining shop, or they’re drilling a hole in a product during manufacturing of that product, understood that the quality has to stand up to the name Sikorsky. Throughout the years, that’s the legacy, and that’s the legacy going forward, and everybody there today will have a part of it.

Everybody who retired from Sikorsky says, “When I come back over the Igor I Sikorsky Memorial Bridge over the Housatonic River, I love that place.” There was something about the camaraderie at that time. It wasn’t just because we won the UTTAS competition. That’s the way we were. If you wanted to move Sikorsky helicopter, the entire building, to the left 4 inches, you would go to the factory and say, “I need to move this company, the whole building 4 inches to the left,” they would do it. There’d be a scramble. Everybody would go crazy to do it because that’s the way they did it.

I think that the evolution of Sikorsky required this. Back then our evolution was to develop a stronger manufacturing capability and get into digitization. But that has now gone so far beyond those capabilities.

In conclusion, the name of the founder was inherent throughout the culture of the company. You could visualize the man because he was always there. You could visualize the culture that he had created. He was the founder.

When I was president of the company, I created a slogan – “The Sikorsky Family,” because it really was a family. I it was a phrase symbolizing the Sikorsky family because it really was a family.

Bill Paul, 2023

Articles about Bill Paul

Bill Paul: Reflections on Sikorsky’s 100th Anniversary

Former Sikorsky President Bill Paul reflects on his career with Sikorsky, meeting Igor Sikorsky, and the Sikorsky Aircraft Company’s 100th anniversary.

Bill Paul: Management Contributions to the Black Hawk Helicopter’s Success

Bill Paul recollects one of the key milestones of Sikorsky history, the win of the UTTAS program that became the Black Hawk helicopter.

Timely Win of the Black Hawk Helicopter

Late in the afternoon on December 23, 1976, Sikorsky received a telephone call that will likely rank as the most important call in its 90 year history.