Sikorsky Aviation History

Wings Over The Atlantic

by Mitch Mayborn, August 1972

This essay is a reprint of an article which appeared in WINGS Magazine in August 1972. It appears to be historically accurate but as with any older historical event there are always three different versions of what occurred.

WINGS OVER THE ATLANTIC

By Mitch Mayborn

On September 21, 1926, the first attempt at a non-stop flight across the Atlantic Ocean from New York to Paris ended in failure. At stake was the $25,000 Raymond Orteig prize and a large share of aviation history. Events from the first conception of the idea to the choice of pilots to the final days of testing bespoke tragedy. Fraught with controversy, indecision and just plain bad luck, the ill-fated venture had little chance at success from the outset.

During the following spring, another, far less imposing assault would be made on the Atlantic. Modest in its single engined equipment and one man crew, it would succeed where a giant trimotor had failed. But that is another story. This account is not as well known … failure seldom is. But had the men who launched their campaign to fly the Atlantic, one year before Charles Lindbergh did it, planned more carefully, theirs might have been the glory. They had an exceptional aircraft. Their pilots were well known, if not experienced in multi-engined aircraft, and they had the backing that Lindbergh did not. Still,

they failed. Yet their failure was but another chapter in the heritage of flight.

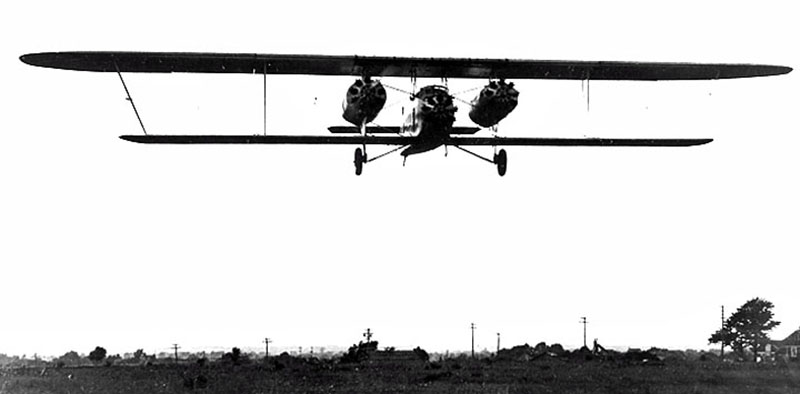

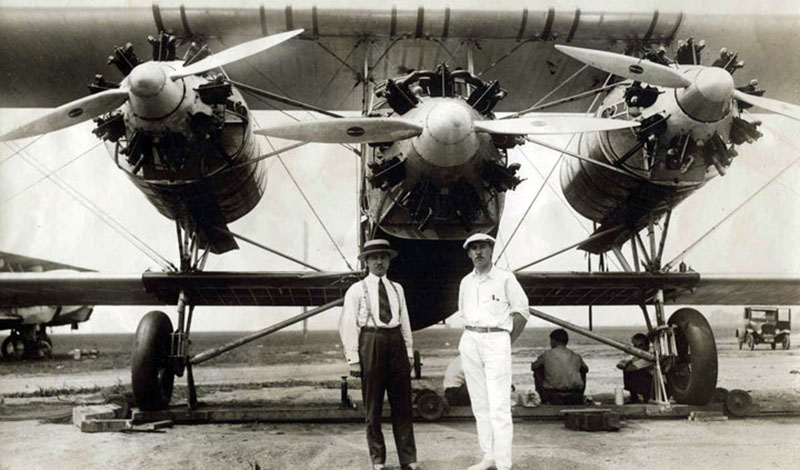

This History of the airplane which was to play the major role in the first New York to Paris flight was the big trimotor Sikorsky S- 35. Clumsy by today’s standards, the aircraft was an aeronautical innovator in 1926 and remarkably free of drag for a three engine biplane, its wing-mounted engines faired into streamlined nacelle tubes, braced between upper and lower wings with a minimum of extraneous support.

Originally intended for a commercial airliner, it had been extensively modified for the long distance flight. The wings were extended to 101 ft. and were strengthened to hold extra fuel tanks. At the same time, the interior structure was lightened so that the- major portion of the load could be in fuel and oil. Thus, the empty weight of the big S-35 was only four tons.

An all metal structure covered by fabric, the entire frame-work of the body was composed of duralumin channels, tubes and plates assembled with steel bolts and rivets. There was no welding on any part of the structure and there were no wires or structural cross members in the cabin area. The entirely enclosed cockpit had shatterproof, sliding glass windows at the top and sides, and dual controls had been provided for the pilots. Behind the cockpit the passenger cabin contained space for 450 cu. ft. of cargo or 12 passengers. This cabin was four ft. wide, six ft. high, and fifteen and one half ft. long. At the front of the cabin were two doors which gave access to the wing, enabling mechanics to inspect the wing mounted engines while in flight. Radio equipment was also installed for regular or short wave transmission.

Sikorsky had fitted self-compensating rudders on the S-35, so the plane could fly level with any two of its three engines in operation. Its wing structure was made up entirely of duralumin, with the main spar built up to I-section by four duralumin angles, riveted to the central web of flat sheet duralumin. These ribs were formed from light sheet duralumin channels and angles, and high tensile strength tie rods were used in the internal drift bracing system.

The ailerons were hinged on an auxiliary spar behind the main spar. They tapered at the tip and blended into the

wing at point of attachment. Tail surfaces were built similar to the construction of the wings and were fabric covered. The stabilizer was adjustable for trim during flight, while the landing gear, of the divided axle type, was made entirely of steel and bolted together, the wheel spread of the gear being 18 ft. 4 in.

The S-35 was capable of flying 4,330 miles, and of taking off at the proposed weight of 24,200 pounds with a 21.85 pound wing loading. Its three Gnome- Rhone Jupiter engines developed a total of 1,260.horsepower, enough to sustain flight on any two operating engines. Just before the flight, designer Igor Sikorsky proclaimed, “The plane is in as excellent condition as any machine has ever been.” And yet the venture failed. leading up to the final tragic conclusion of what could have been one of aviation’s most historic flights, a series of minor accidents were to occur, culminating in the fiery crash of the S-35 and death of two men.

Things began going wrong from the beginning. To start with, one of the originators of the flight idea, Captain Homer Berry, United States Army Air Service, Ret., was informed that he would accompany the trip, only if there were three pilots. Berry replied bitterly in a statement to the press, “Two years ago I got the idea of this flight and went around the country getting backers for the project. I was at that time told that I would be pilot of the attempt as soon as the plane was ready. I then went to South America on a business trip and when I returned was informed I would be co-pilot. Now I find that I am out in the cold altogether.”

Claiming he was betrayed by his back- ers, Berry and Captain Rene Fonck, now the chief pilot, were to continue arguing for several weeks, but to no avail, Homer Berry was out. But he would not be the first, nor the last. French Air ace, Rene Fonck, credited with 75 German kills in WW I, and with claims for 50 more, had been selected as chief pilot for the trip with a weekly salary of $250 and the power to choose his crew. During the war, the fighter pilot had been decorated 24 times, for bravery in combat, but never, it seemed, for tact or diplomacy.

Backing the flight was the organization known as, The Argonauts, Inc. Robert Jackson, paper manufacturer from Concord, N.J., was its president and, at the time of the Berry-Fonck argument, he was in Paris “awaiting” the arrival of the S-35 and its crew. Vice-President of the Argonauts was Colonel Harold E. Hart- ney, wartime commander of the U.S. First Pursuit Squadron in France. Hartney who had managed the tempestuous American ace, Frank Luke, was the coordinator of the project on the American side of the Atlantic. There were conferences. Bernard Sadler, attorney for the Argonauts, arrived at the airport radiating determination and left two hours later downcast. He had, along with Hartney, Berry, Lt. Allen Snody, Fonck, and an interpreter, been discussing the problem of the pilots. Sadler told Fonck, “You are just an employee and can be fired at any time.” He further intimated that this just might happen if the row wasn’t settled soon. The group huddled in a corner of the hangar. Sadler talked. Hartney talked. Fonck talked. The interpreter talked. Berry listened. Pencils were tapped on chests, hands were waved, but the message was plain-Berry would have to go. Fonck, the dapper little French ace, looking like he had just stepped out of a cigarette ad, was apparently too cocky for Berry. At one point in the disagreement, with Fonck officially in as chief pilot, Hartney in as arbitrator, and Berry out in the cold, Fonck said, “Homer Berry did not get his rank of Captain from the United States Army. He got it from a ‘business trip’ to South America when he fought for Pancho Villa in Mexico. He fought for both sides for the fun of it. In the American army in France during the war he was only a sergeant. He.is trying to force my hand, to make me take him along. Perhaps at the end of the week I will announce the names of the men of my crew-a radio operator and a mechanic-but I will not take Berry. About 200 pilots in America have asked for permission to go along, and as many in France, naturally Berry is disappointed, but he is an outsider.” At this last statement, Berry bristled. “So he calls me an outsider does he? I’ll show him that he is badly mistaken. No Frog, no matter how many medals he has, can come over here and push me out of this flight.”

However, four days later on Sept. 4, Captain Homer Berry dropped out of the flight and gave up all claims to the honor pf piloting the S-35- across the Atlantic. This gave U.S. naval pilot, Lieutenant Allan P. Snody, an aide to Navy Air Chief, Rear Admiral William A. Moffett, clear sailing as official co-pilot to Fonck, and he was immediately given leave to participate in the New York to Paris flight.

Berry’s dropping out by no means cleared up all of the controversy. Petty jealousies, some of them idiotic, re mained. In the midst of the Fonck-Berry row, Lieutenant G. O. Neville, an auto- motive engineer for the Vacuum Oil Co., and flight engineer on the New York to Paris S-35, withdrew from the organization. In the race for endorsement money, a dispute had arisen over the oil to be used for the flight. Lt. Noville, who had been with Commander Richard E. Byrd on his Polar flight in a similar capacity, stated that Gargoyle Mobiloil “B” would be used on the Trans-Atlantic attempt. Fonck, who had already pocketed the cash, said that a British motor oil would be used. Noville quit. Prior to his work on the S-35, Noville had used the same oil in the Josephine Ford, Byrd’s Fokker, and had found it satisfactory, even in the arctic conditions encountered. But Fonck had, evidently, found the British lubricant even more satistactory, and with his palm well greased, the British motor oil was in and Mobiloil, like Berry, out.

Meanwhile, promoter Robert Jackson, still in Paris publicizing the forthcoming flight, dismissed the bickering as minor. He told reporters that the difference of opinion among the prospective crews had been blown out of all proportion and assured them that Noville couldn’t have resigned as flight engineer, since he had never been promised the position in the first place, much less been given it.

But while what had gone before could be glossed over, there was no way Jackson could ignore a big problem which was now becoming acute. Who was going to pay for the giant S-35?

As of September 4, 1926, the Argonauts had paid a total of $20,000 on an airplane which cost $105,000. Jackson had contributed $10,000 and John Jameson of Concord, Mass. had put up another $10,000; and that was all. Caught in the middle, and obviously aware that he would be forced to pick up the balance, Igor Sikorsky donated the remaining $80,000. Becoming an aviation pioneer was getting to be an expensive past time, but he consoled himself with the fact that a successful crossing of the Atlantic by the S-35, would flood his company with orders.

At this point several other “arrangements” previously made by the dapper wheeler-dealer, Rene Fonck, emerged. As part of his agreement with the Argonauts and Sikorsky, Fonck was to have secured three British designed, F re n c h – built Gnome-Rhone Jupiter engines from the French government, at no cost. This was the major reason why he had been given the position as chief pilot. War record notwithstanding, $43,000.00

worth of advanced aviation engines was a big inducement to accepting Fonck over Berry.

Unfortunately for the Argonauts, the engines had not materialized as Fonck had promised. They had to be paid for. Vice President Hartney, acting as comtroller was indignant. At one point, with a suit threatened, he produced a bill of sale dated April 2, which stated that the Argonauts had paid all but $8,000 of the engine costs. He stated that the balance would be offered later the same week, and added that the engines which were to have been free had, indeed, cost them $43,000, which brought the total price of the plane to over $150,000. During the period of controversy between Fonck and Berry, over piloting, Fonck and Noville over the oil, and the Argonauts, Fonck and Sikorsky over payment, flight testing had been going on at a leisurely, if restricted pace.

All flight tests were to have been under the control of Sikorsky and were to have lasted not less than six weeks. Needing to recoup his losses, Sikorsky was to have had the opportunity to test the plane under official auspices to set new records for altitude and speed with heavy loads, all with an eye to gaining publicity and more orders. However, the flight program did not allow the full utilization of the S-35’s capabilities, nor did it successfully probe any possible weak points.

On the morning and afternoon of Aug. 23, the plane underwent two successful flights. In the air for only half an hour in the morning, the afternoon flight lasted over an hour while Sikorsky, Fonck and Snody took turns at the controls.

The flight was along the course of the Harlem River, over Yankee Stadium, down the Hudson River, around the Statue of liberty, across Brooklyn, then back to Roosevelt Field. This was the first real air test of the S-35-but it had lifted a payload of only 4,000 pounds, or one fourth the load to be carried to France. At one time during the flight, the center engine was cut and, as Sikorsky had guaranteed, the S-35 had sufficient power remaining to climb.

When the plane set down, Sikorsky was seized by a dozen of his Russian countrymen employed at the field, and

carried shoulder high from the runway. Meanwhile the S-35 was taken to the hangar where final streamlining and the installation of long range gas tanks was completed.

Snody, as co-pilot and navigator had been working on weather charts and maps for several weeks, compiling re- ports from up to 40 ships at sea each day. He stated that approximately 70 percent of the time, the wind would be favorable. The course would be 3,611.8 miles long, of which 1,900 miles would be over water.

The tests continued. After one flight, the plane’s left wheel stuck in a hole in the runway but there was no damage, and on Sept. 8, Mayor Jimmy Walker of New York City christened the plane the New York-Paris. On the 9th, Fonck flew the S-35 and 13 passengers from Roosevelt Field to Washington, D.C. Cruising at 120 mph, at 350 rated horsepower, per engine, the S-35 made the trip in two hours against a stiff headwind. At Washington there were no hangars large enough for the giant so it had to be left in the rain overnight. To keep the curious away, a naval guard was posted.

After returning to Roosevelt Field the next day, it was announced that this was one of the last times the S-35 would go up except for the official weight lifting, speed and altitude tests.

There were still a number of changes to be made on the big record breaker. The tail skid was replaced by a wheel so that there would be less ground drag during take-off. And to beef up the undercarriage, an auxiliary landing gear of four extra wheels was installed behind the main gear. Sikorsky noted that, on the last flight prior to the trip, these wheels will be dropped to test the re lease mechanism. They can be rebuilt easily if they are smashed. They are needed to help support the S-35’s weight, but Captain Fonck doesn’t want them to cause drag or comprise an extra load across the Atlantic, so they will be dropped as soon as he gets over water, probably in Long Island Sound.”

Tension was at a high pitch during the last few days of flight preparation. Lieutenant Snody, who had been sick with a cold for several weeks developed acute bronchitis which affected his breathing, eliminating him from the trip.

Speculation arose as to the identity of the new co-pilot. Early on the 13th, U.S. Navy Lieutenant Frederick Nelson left the field with Fonck. Later he returned with a new flying suit and a number of smoke bombs for drift detection. It appeared that he would accompany Fonck, but on the 14th, it became apparent that Lt. Nelson would not go either. Lieutenant Lawrence William Curtin, also of the U.S. Navy, arrived at the field, and it was announced that he would fly with Fonck. Bubbling with enthusiasm, Curtin jumped at the chance to go. He had been an aid to Commander John Rodgers who was killed attempting the first long distance flight to Hawaii.

This sudden chance to go to Paris, however, did not interrupt Curtin’s plans to fly to Panama with two Navy planes from Philadelphia. “I’ll do that when I get back. It isn’t until October.” Berry, ‘On hand all this time, noticed Curtin had no flying gloves and ran to his car at the side of the field and gave him his own.

Curtin also re-routed the schedule flight saying that it was longer than necessary. He changed the course to a great circle route which cut north of Cape Cod, bisected Nova Scotia and Bonavista Bay, Newfoundland, and came out on a wide, sweeping curve far north of the steamship lanes. The route returned to land about ten miles south of Cape Clear, Ireland, then over Falmouth, England, Cherbourg and on to LeBourget in Paris. This great circle route was 114 miles shorter than the previous one, making the projected flight a total of 3,497.8 miles.

Sept. 16th arrived. In the early dawn the big S-35 was wheeled to the end of the runway, its exhaust stacks spitting fire. The field had been carefully gone over during the week and all holes and depressions had been filled. As the plane was being fueled in the early dawn a leak developed in the right outboard gas tank. At first only a trickle, it quickly developed into a steady spurting stream. The flight was quickly aborted, because the time required to make repairs would force the plane to land in Paris after dark. Despite the fact he had been pushed out of the flight, Berry helped to pump gas by hand when the field generator overloaded and quit. For four days bad weather prevented take off. To bystanders, it seemed that everyone was continually glancing aloft, vainly attempting to tell the state of the weather off the Grand Banks by sniffing the air of New York. The whole world was waiting, and as it did, a message to Lt. Curtin from President Coolidge was received.

“I am glad to extend to you and Captain Fonck good wishes for the success of your flight. I hope that this may prove not only a fine and courageous adventure, but a step in the development of aviation which shall bind closer together the countries of the world.”

CALVIN COOLIDGE

Captain Fonck received a similar, but not so friendly message from Captain Wesier of France, who had only a few days before set a world’s record flight of 5,200 kilometers between Bandar Abbas in Persia and Paris. His read: “Start, even if it means that you will fall into the sea and have to swim.”

In the darkness of the early dawn of Sept. 21, the S-35 was again hauled to the end of the runway at Roosevelt Field. Men swarmed over the big trimotor, tightening every nut and bolt for the last time. The struts, fuel lines, hinges, motors, anything that could be reached was checked again and again. Lights flashed in and out of the cockpit where a final check was given the instruments.

Rene Fonck appeared, resplendent in his blue French uniform, his short legs encased in leather puttees. Casually remarking in typical French fashion, “Tuesday, Wednesday . . . dinner in Paris? Who knows?” he tossed an imaginary toast towards his lips. U.S. Navy lieutenant Bill Curtin also arrived in his service uniform, flashing his boyish grin in suppressed excitement. Both uniforms were quickly covered by flying suits as the men got to work.

The other crew members arrived. The Frenchman, Charles Clavier, was on hand as radio operator. Clavier was returning to his wife and three children loaded with gifts, as he did not anticipate returning to the United States. Friendly and well-liked by everyone because of his cheerfulness, Clavier had helped install the radio equipment. Also on board the plane was Jacob Islamoff , in charge of fuel consumption on the S-35. A refugee, he had graduated from the Russian Naval Academy during the first part of World War I, and had been a radio operator on a Russian Polar expedition. For three and a half years he had worked in a Russian observatory in Constantinople. He was returning there to visit his parents.

There was anxiety at the field as the three Jupiter engines roared into life. The plane, originally designed as an airliner, then converted for the long range flight, was designed to take off at a gross weight of 24,300 pounds with a wing loading of 21.85 pounds. However, it was found, just prior to take-off, that the weight was 28,000 pounds, two tons more than planned, giving the S-35 a wing loading of 26 pounds per square foot. It was now so heavily loaded that its wheels sank into the dry turf.

Things started going wrong as soon as it was taxied from the hangar to the end of the runway. Purple flame spitting from the exhausts in the darkness, the S-35 moved towards the end of the runway, then the tail skid slipped off the dolly, bending the lower end of the center rudder. It took only a minute to fix, but the signs were ominous. Then in turning the plane around toward the west and the mile long runway, one of the auxiliary wheels was bent. This too was straightened, and the flight pronounced ready.

Cars raced downfield to watch the take-off. With men pushing the over- loaded plane to get it started, the three Jupiter engines strained forward, the propellers tearing into the still morning air. A long cloud of dust engulfed the ground crew as the S-35 lumbered down the runway.

Calculations called for a take-off run of 2,200 ft. in 51 seconds. Igor Sikorsky stood watching the plane move down the asphalt, his fists tightly clenched, straining with his body to help his creation into the air. Three hundred yards from the start, a series of small bumps marked the spot where a road crossed the field. Two thirds the distance of the field there was another road and more bumps. Fifty yards from the end of the runway, just before a twenty foot embankment was reached, there were two more roads.

The start made, the floundering, overloaded S-35 moved forward. Then, without warning, it began to come apart. As it bounced over the first bumps, an auxiliary wheel tore loose, spun around and leaped into the air. The plane lurched to the left but Fonck and Curtin were able to control it. Then the right auxiliary gear started to fall off. The wheels flew into the air, dropped and spun away. Now the wheel under the tail skid gave way, dropping the empenage heavily on the skid. One of the auxiliary wheels hit the lower part of the left rudder, breaking it loose and partially caving in the tail section. As if gripped by a giant fist, the tail was dragged along the ground, holding the plane to the earth.

The struggling S-35 made a little hop, but the immense drag pulled it back down. The end of the runway was reached. Its long wings outstretched, the giant inched out over the top of the 20 ft. embankment and dropped out of sight.

There was a long moment of suspense. Then, just as the racing cars reached the crest of the hill, a great ball of flame shot up from the plane, searing the countryside with its 2,500 gallons of gas and oil. The roaring inferno that was the crumpled plane lit up the early dawn darkness with an eerie orange glow, casting long shadows behind the spectators.

Mouth agape, eyes rolling, Sikorsky outdistanced many younger men in the dash to the wreck. Captain Berry, with tears streaming down his face and crying, “What a shame! What a shame!” had to be held back from dashing into the inferno to save the trapped men.

At first it was thought that everyone was killed. Then a dazed and shocked Fonck, tattered and bleeding appeared. Next Curtin came up, marked only by a little soot but outwardly composed. Inside the crushed S-35 were Clavier and Islamoff .

Fonck and Curtin had escaped through a hole in the top of the cabin. They had crawled free, dodging a still turning propeller. Hoping that their companions were safe, they barely had time to clear the wreckage before the thousands of gallons of fuel burst into flame, consuming the entire plane. Fire trucks from nearby Mitchell Field were helpless. Finally, after an hour of intense flame, the fire died down.

Fonck later stated that he had seen soon after the start of the flight that he not only couldn’t take off but could not control the 14 ton monster. His only chance was to continue at full power and hope to clear the drop off at the embankment, and land straight ahead. As the S-35 hopped the top of the bank and glided down, the right gear struck then, on the second bounce, collapsed, buckling the right wing.

Later the same day, showing his strong spirit, Curtin said, “It was the fortune of the air, it could’ not be helped. Now is the time for you fellows to get us another plane.”

Immediate reaction of the flight’s failure was shock. However, when the shock wore off, there was a demand for an investigation of the cause. Some thought overloading did it; others thought that Fonck was at fault. Very few blamed the Sikorsky S-35.

At the inquest a few days later, Col. Hartney testified that in his opinion, “Fonck was incompetent. He demonstrated poor pilotage and irresponsibility and there was a lack of preparation for the flight.” Hartney further added that there had been no teamwork in the crew and that Fonck wanted all of the prize money and publicity.

The French also criticized their one- time hero. An official in the aeronautics branch advised that, “Fonck had no value whatsoever as an experimental pilot. It is a special profession, requiring highly technical training. A fighter pilot is one thing and a test pilot is another.” Other capable persons said he had too little practice time in the S-35 and very little time in multi-engine aircraft. Many jumped to his defense though. Lt. Curtin said that he would fly in anything, anywhere, provided Fonck was pilot.

At first Fonck blamed Islamoff for releasing the auxiliary wheels. However, a few days later he retracted this statement with the comment that he had misunderstood the situation. It had appeared to him that had panicked when the wheel assembly was smashed and had released it. By-standers took issue with Fonck, saying the gear had gradually broken up along the entire course, rather than come off all at once.

Sikorsky believed there were two major causes of the crash. The first was a last minute shift of the wind to the east. This wind change forced the takeoff along the prepared runway to be downwind. He listed as the second cause, the damage to the auxiliary gear and the resultant drag.

The general consensus was that there were several related causes. The big S- 35, great machine that it was, was obviously very heavily overloaded and had not been tested fully in that condition. The rough field caused the initial damage to the plane and the dragging parts held it back, keeping it from attaining flying speed. The tailwind further complicated the take-off, and in light of the need to get airborne quickly, while heavily laden, the downwind take-off had been disastrous.

However, experienced pilots who had witnessed the crash stated that the plane, overloaded as it was, could have flown had Fonck raised the tail. The engine switches had three separate cut offs. George Honneur, French engine expert, who had installed the Gnome-Rhone Jupiter engines, said that had there been a single cut off, and had Fonck been able to cut the ignition, it is possible there would have been no fire.

In a general whitewash, the Grand Jury holding the inquest turned in a verdict that it was an unfortunate accident and all concerned with the flight were cleared. Igor Sikorsky said simply, “We will go ahead. Aviation must be prepared to meet these things as they occur. From the disaster itself may come great strides forward. No one who flies ever becomes disappointed by death and discouragement.”

The first attempt a non-stop flight between New York and Paris ended, but the lessons gained from the tragedy on Sept. 21, 1926, when the beautiful Sikorsky S-35 was destroyed and two brave men were killed, were applied almost nine months later when a lone pilot, in a single engined monoplane completed the great journey that made his name immortal.

| SIKORSKY S-35 SPECIFICATIONS | |

| Span, upper wing | 101 ft. |

| Span, lower wing | 76 ft. |

| Height . | 16 ft |

| Total wing area | 1,095 sq. ft. |

| Weight empty | 8,000 Ibs. |

| Loading per horsepower | 19 Ibs. |

| Loading per sq. ft. of wing area. | 21.85 Ibs |

| Crew | 510 lbs. |

| Special equipment . | 590 lbs. |

| Total weight of fuel and oil .. | 15,200 lbs. |

| Total weight of S-35 | 24,300 lbs. |

| Gnome-Rhone Jupiter engines | 420 hp. |

| Maximum speed | 148 mph |

| Cruising speed | 120 mph |

Prepared by Vinny Devine

January 2016