Sikorsky Builds Big – the S-56

The large and powerful Sikorsky S-56 was Sikorsky’s answer to the U.S. Marine Corps’ request for a shipboard helicopter that could carry heavy loads on amphibious assaults.

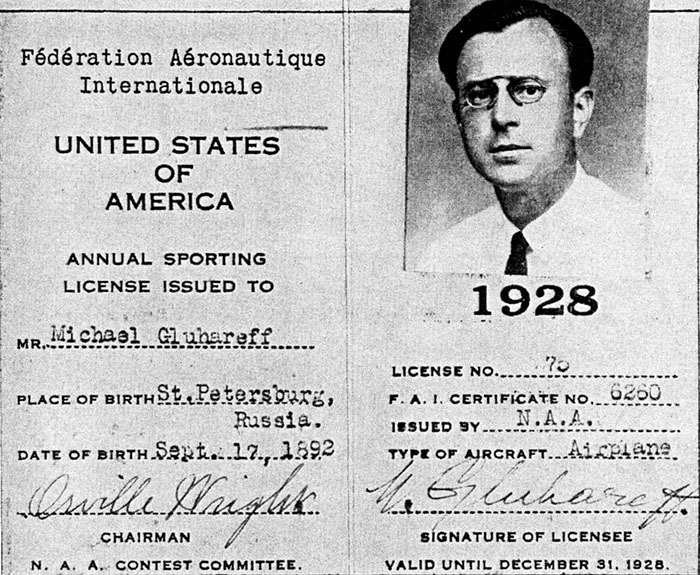

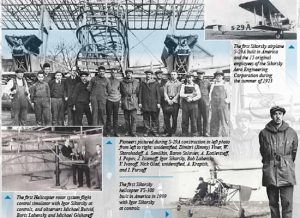

When Michael Gluhareff immigrated to the United States in October 1924, he arrived with dreams of becoming a successful aircraft designer in a country he believed would be full of opportunities in aviation. He had left behind his home country of Russia, which was torn apart by civil war following World War I, and then Finland, where he devoted his time living in exile to learning everything he could about his favorite subjects: aircraft design and aerodynamics. Soon after his arrival however, Michael was disheartened to find that America’s aviation industry was still in its infancy, with very few aircraft manufacturers and even fewer aviation-related jobs available.

At that time in the early 1920s, America’s commercial airline transportation industry did not exist yet, and the general public had very little interest in aviation. Michael was even more discouraged when he tracked down Igor Sikorsky, the legendary aircraft designer of Imperial Russia, and found that he and a group of Russian émigrés were struggling to build an airplane with meager funding and establish an airplane company.

It might have seemed impossible to Michael at the time, but with the innovative aircraft he would create throughout his lifetime, he would not only play a critical role in making Igor Sikorsky’s aviation company a successful business, but he would also be considered a pioneer in the aviation industry. At the Sikorsky Aircraft Company, Michael Gluhareff and Igor Sikorsky worked closely together to design the company’s industry-defining aircraft, which included amphibious airplanes, flying boats, and helicopters. Michael Gluhareff would eventually succeed Igor as the company’s second engineering manager.

Michael’s creative ideas for new kinds of aircraft continued past the end of his workday at Sikorsky. In his spare time, he designed ground-breaking aircraft that the world had not yet imagined, including high-speed, tailless, delta wing aircraft and extreme high altitude sail planes. By the end of Michael’s career in 1964, Igor Sikorsky regarded Michael Gluhareff as one of the best aircraft designers in aviation history. With his patents for delta wing aircraft, he is also the inventor of the delta wing for high speed and supersonic flight.

Early Life in Russia and Finland

Born in Saint Petersburg, Russia on September 17, 1892, Michael Gluhareff grew up in a wealthy family who owned an industrial empire in Russia, with businesses in steel, hardware and machinery. Given his upbringing, he would have been destined to spend his entire life working for his family’s company if it had not been for an event that deeply inspired him: the historic first aircraft flight across the English Channel in 1909 by French aviator Louis Blériot.

Blériot had become celebrated as an early aircraft designer and pilot when he entered and won the Daily Mail Prize, a £1000 prize competition to cross the English Channel by aircraft that Paris newspaper Le Matin said there was no chance of winning. Deeply inspired by this accomplishment, Michael enrolled in the Saint Petersburg Polytechnic Institute of Technology in 1910.

It was during his first year at school that Michael designed, built and flew his first glider, around the same time that Igor Sikorsky was flight testing his first few airplanes in a farm field outside of Kiev. Following graduation, Michael entered and graduated from the Imperial Military Engineering College in Saint Petersburg, and then with the outbreak of World War I, he became a pilot for the Russian Army. Michael Gluhareff later told the Bridgeport Sunday Post in a December 1964 interview, “I suppose I flew maybe 60 sorties in the war, all kinds of planes. I used to move from one outfit to another just to fly different planes.”

During the Russian Revolution at the end of World War I, Michael Gluhareff joined the White Russian Army as a tank driver and a pilot, but when their cause became hopeless, he fled to Finland to join his family in exile. It was there in Finland from 1920 to 1924 that he devoted himself to learning everything he could about aircraft design, and in particular, aircraft aerodynamics.

Exile gave Michael plenty of opportunity to study the theories of the leading aerodynamic authorities of the time, including Prandtl, Pietzch, Skopik, Eifel and Joukovsky, Pippard and Pritchard, and Martens. He tested those theories by designing and building gliders and sailplanes with his brother, Serge Gluhareff, and then flying them, using nearby farm fields as runways. Michael spent those years in Finland looking for opportunities to pursue a career in aviation, and by 1924, he and his brother Serge decided to leave for the United States, where they felt those opportunities were sure to exist.

America in the early 1920s was a period of recovery from World War I, when Americans wanted to enjoy themselves and began to value convenience and leisure. At the time, there was very little interest in aviation, aside from veteran pilots who served in World War I, and the aircraft market was oversupplied with a glut of small, single-engine aircraft left over from the War. The most common of these small aircraft was the Curtiss JN “Jenny” biplane, which sold for bargain prices. Because of this, very few new aircraft models were in development, and opportunities for aircraft designers were scarce. As demoralizing as this was to Michael, he was even more discouraged when he visited Igor Sikorsky, and found he was struggling to start his own aircraft company in a small, drafty aircraft hangar at Roosevelt Field, in Hempstead, New York.

Igor Sikorsky was a legend in Imperial Russia, where he was famous for creating the world’s first multi-engine aircraft, the S-21 “The Grand”, as well as the larger, more powerful Ilya Muromets, flown by the Russian Army throughout World War I. At Roosevelt Field however, Sikorsky and a devoted group of poorly paid Russian émigrés were struggling to produce their first aircraft, the S-29-A, which was constructed using scrap metal and materials salvaged from nearby junkyards.

Unlike the small, single-engine, open cockpit aircraft that flooded the market, Igor Sikorsky’s S-29-A was a large 14-passenger transport aircraft with an enclosed, comfortable cabin and the safety of multiple engines. The commercial industry for large passenger aircraft did not exist in the early 1920s, but Igor Sikorsky had the vision that, with the geography of the United States, the use of large aircraft for passengers and mail transportation was certainly in its future. Motivated by his vision, Michael and his brother Serge both joined Igor Sikorsky’s company, with Michael starting as a draftsman with a salary of $15 a week, when he was paid at all.

Igor Sikorsky’s Chief of Design

Soon after he started with the Sikorsky Aircraft Company, which was then called the Sikorsky Aero Engineering Corporation, one of Michael’s co-workers, Alex Krapish asked him to design a special barnstorming airplane for him that he could use for stunt flying. With Igor Sikorsky’s permission, Michael used part of the company’s hangar at Roosevelt Field to design and build Alex’s airplane, and while the resulting aircraft was very impressive, the truly remarkable part of its design was its wings.

For the wing design, Michael chose a sesquiplane wing configuration, in which the lower wing has a significantly shorter span than the upper wing. This design gave his aircraft the advantage of reduced weight and drag while retaining a biplane’s structural advantages. In addition, he used an airfoil design of his own creation, which provided better speed, lift and efficiency than other aircraft wings of the time. Michael said that the airfoil’s design came to him in a dream, and he soon realized that the wings from this stunt flyer airplane could be adapted easily to many other airplane types of that era, including the Curtis “Jenny”, and greatly improve their performance. For example, when it was installed on a Curtiss Oriole, the aircraft flew 30 miles an hour faster and could carry an additional passenger. He called his innovative wing design the GS-1 (G for Gluhareff, S for Sikorsky) and customer demand for it was immediate. 20 GS-1 wing kits were sold between 1925 and 1927 for a price of $2,000 including installation. In addition to wing kits, Igor and Michael developed and sold three new single-engine airplanes featuring GS-1 wings: the Sikorsky S-31, S-32, and S-33. The sales of these wing kits and airplanes provided the Sikorsky Aircraft Company with its first income, which it desperately needed for new aircraft development. Igor Sikorsky was so impressed with Michael’s achievement that he promoted him to the role of Chief of Design, a position he held until 1942. In fact, his GS-1 wing design was used on almost every airplane, amphibian and flying boat that the Sikorsky Aircraft Company developed from that point forward.

As Chief of Design, Michael Gluhareff collaborated closely with Igor Sikorsky on the development of all of the company’s aircraft. He was responsible for approving the final design of each aircraft, so his signature is found on all final aircraft drawings, alongside the signature of Igor Sikorsky. Between 1926 and 1927, Michael worked with Igor Sikorsky to develop the multi-engine S-35 and S-37 airplanes in a bid to win the Ortieg Prize, the renowned competition to be the first aircraft to fly cross the Atlantic Ocean from New York to Paris, France. Before flight testing could be completed however, the Ortieg Prize was won by Charles Lindbergh in his solo flight from Roosevelt Field to Paris, France in his Spirit of St Louis.

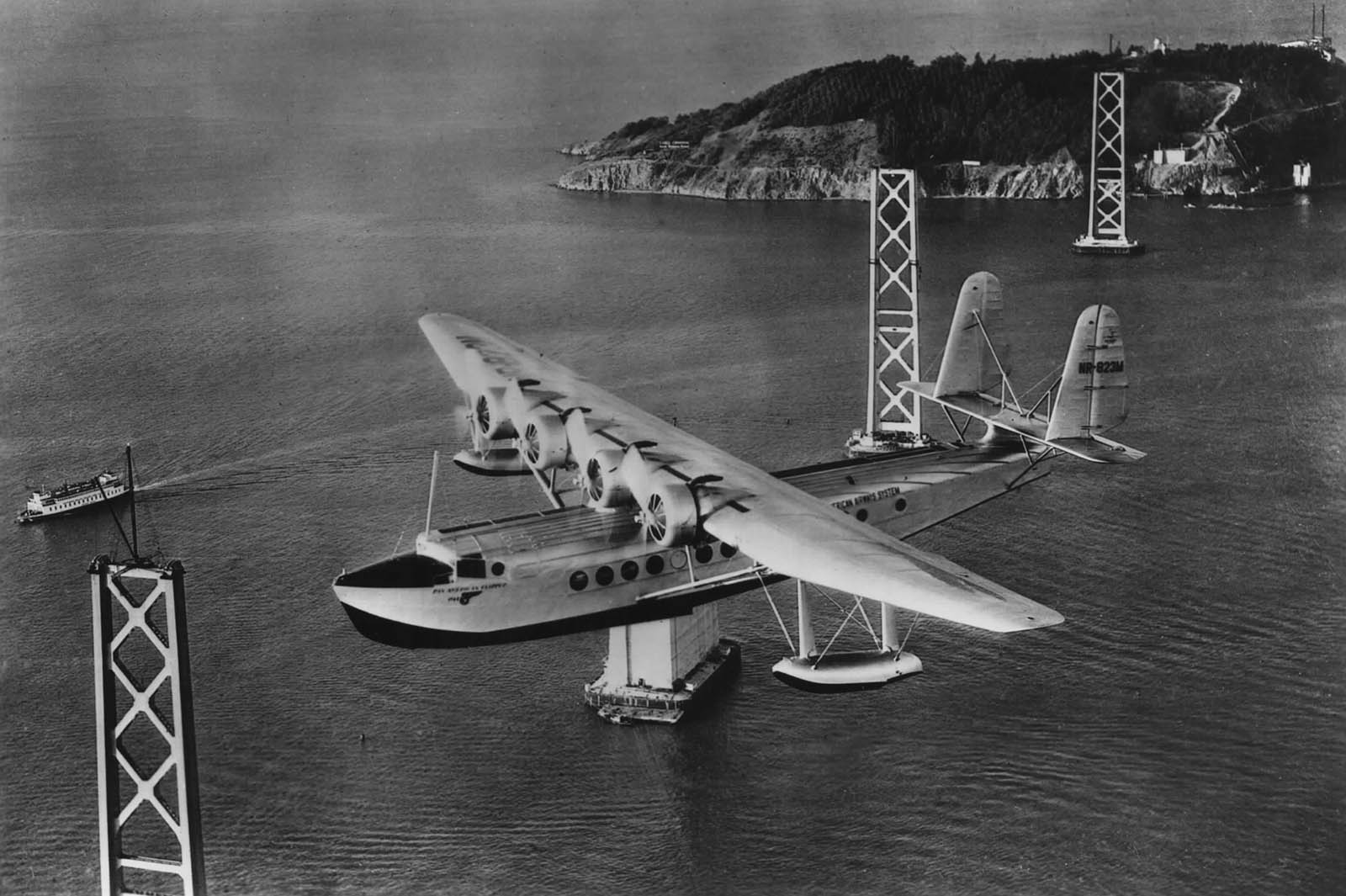

Michael was also essential in developing the amphibious Sikorsky S-38, an innovative 8-passenger aircraft that could land and take off on both solid ground and water. The S-38 is considered the most successful aircraft designed by Igor Sikorsky. Following its first flight in June 1928, 111 S-38s were sold, including 38 for the fledgling Pan American Airways, who used them to establish mail delivery and passenger air routes in the Caribbean.

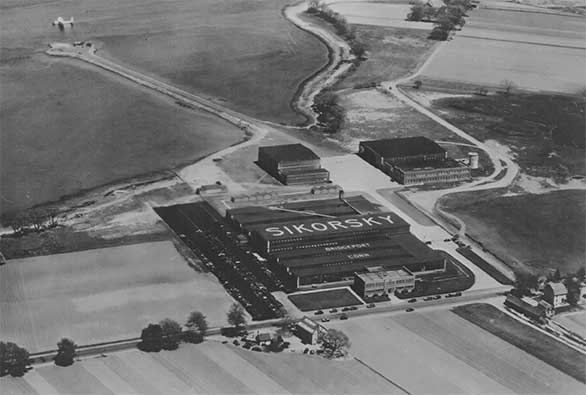

With more Sikorsky S-38 orders than it could handle, the Sikorsky Aviation Company, as they were then known, required a larger, more modern factory with access to deep water for seaplane production. Igor Sikorsky found an ideal location to build this factory along the Housatonic River on South Main Street in Stratford, Connecticut. By 1929, construction of the new factory was finished, employees had completed their move to the new location, and S-38 production was underway.

The success of the Sikorsky S-38 was in some ways the result of the loss of the Ortieg Prize to Charles Lindbergh. Lindbergh’s accomplishment sparked the American public’s interest in aviation and this quickly led to the birth of the commercial airline transportation industry. Igor’s vision had come true, and he had the S-38 ready at exactly the right time to meet the demand of the new passenger airline industry.

Michael’s success as an aircraft designer continued through the 1930s as he led the design and development of Sikorsky’s flying boats, which grew larger with better performance and greater passenger capacity with each model. These aircraft included the powerful 40-passenger Sikorsky S-40, which expanded Pan American Airways’ air routes to Central and South America. They also included the record-breaking Sikorsky S-42, which was the first aircraft to fly routes across the Pacific Ocean to China. Sergei Sikorsky, the son of Igor Sikorsky, described Michael’s design of the S-42 wings as a “masterpiece”. Michael designed the S-42 wing to have high wing loading, which he determined to be optimal for travel at a high cruising speeds over long distance, trans-oceanic flight routes. Sergei Sikorsky explained, “The GS-3 airfoil that Michael put in the S-42 was basically a modified GS-1 with a slight ‘turn-up’ at the tip. At the trailing edge of the wing, [the S-42] had a huge landing flap that was around 70% the span of the wing. It was a very effective piece of design.” Gluhareff’s S-42 wing design resulted in smooth trans-oceanic flights, even in turbulent, stormy weather.

By the late 1930s, sales of Sikorsky’s flying boats declined as the airline industry shifted to using aircraft that could operate from land-based airports. Land-based airports were considered more reliable and less affected by weather conditions and rough seas. Rather than compete with Boeing, Lockheed, and the other companies developing land-based aircraft, Igor Sikorsky made the critical and well-known decision to pivot the Sikorsky Aircraft Company to development of a totally new kind of aircraft: the helicopter.

In a December 1964 interview with Michael Gluhareff in the Bridgeport Sunday Post, Michael admitted that he was initially cool to the idea of the helicopter, and was not in agreement with the major transition the company was taking. His passion was for designing fixed-wing airplanes after all. Gluhareff said however that his first flight in an autogiro in 1938 changed his mind, and from that point forward, he enthusiastically joined Igor and his team to develop and test the world’s first practical helicopter, the VS-300.

While Igor Sikorsky holds many of the first U.S. patents for the design of a helicopter, Michael Gluhareff holds the patents that made important improvements. Chief among these patents, Michael invented the weighted, interchangeable metal rotor blades that were used on all Sikorsky helicopters through the 1960s. He also has patents for the design of a main rotor hub and helicopter horizonal stabilizer.

Inventor of the Supersonic Delta Wing

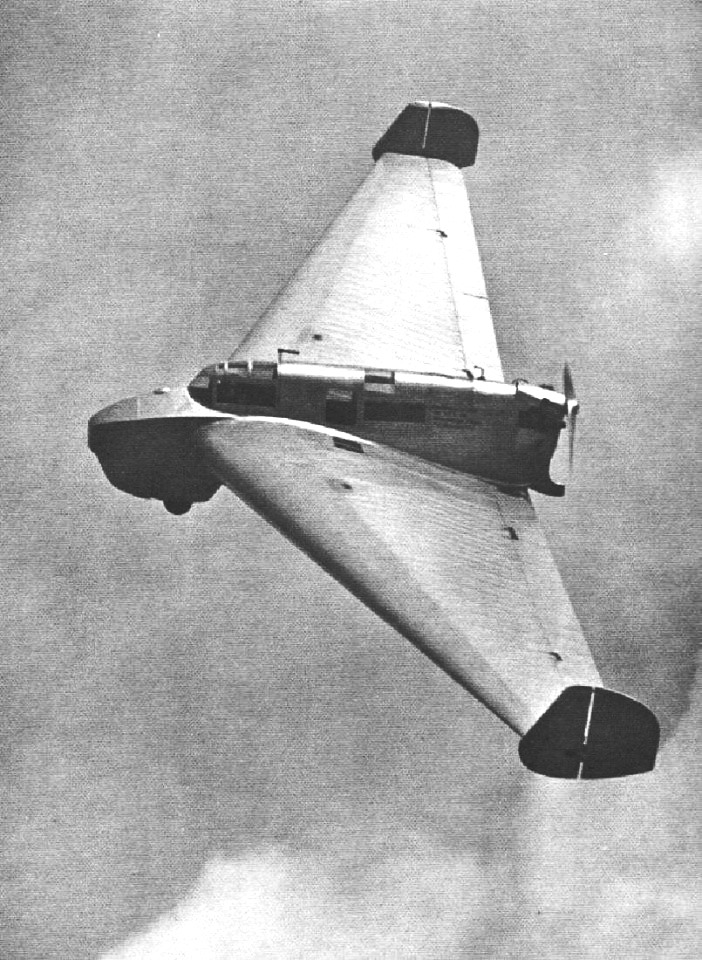

In the 1930s while the Sikorsky Aircraft Company was pivoting its business from developing fixed wing airplanes to helicopters, Michael Gluhareff still had a passion for developing airplanes that he found difficult to ignore. In 1936, while development of the VS-300 helicopter progressed, Michael started experimenting at home in his free time with designs of tailless, delta wing aircraft. Undoubtedly, Michael was inspired by the work of the German aeronautical scientist Alexander Lippisch, who in 1931 designed a delta wing research aircraft called the Delta I. Unlike Lippisch however, Michael Gluhareff realized that by designing an aircraft with a highly swept-back delta wing and innovative control surfaces, it would be adaptable to traveling at extremely high speeds, including speeds faster than the speed of sound.

For many years, Gluhareff continued to work on his delta wing aircraft design. At home, he would spend hours in his office making improvements and then create balsa wood models in his woodshop. Finally in 1941, he felt his design was ready and he brought it to Igor Sikorsky’s office to present to him.

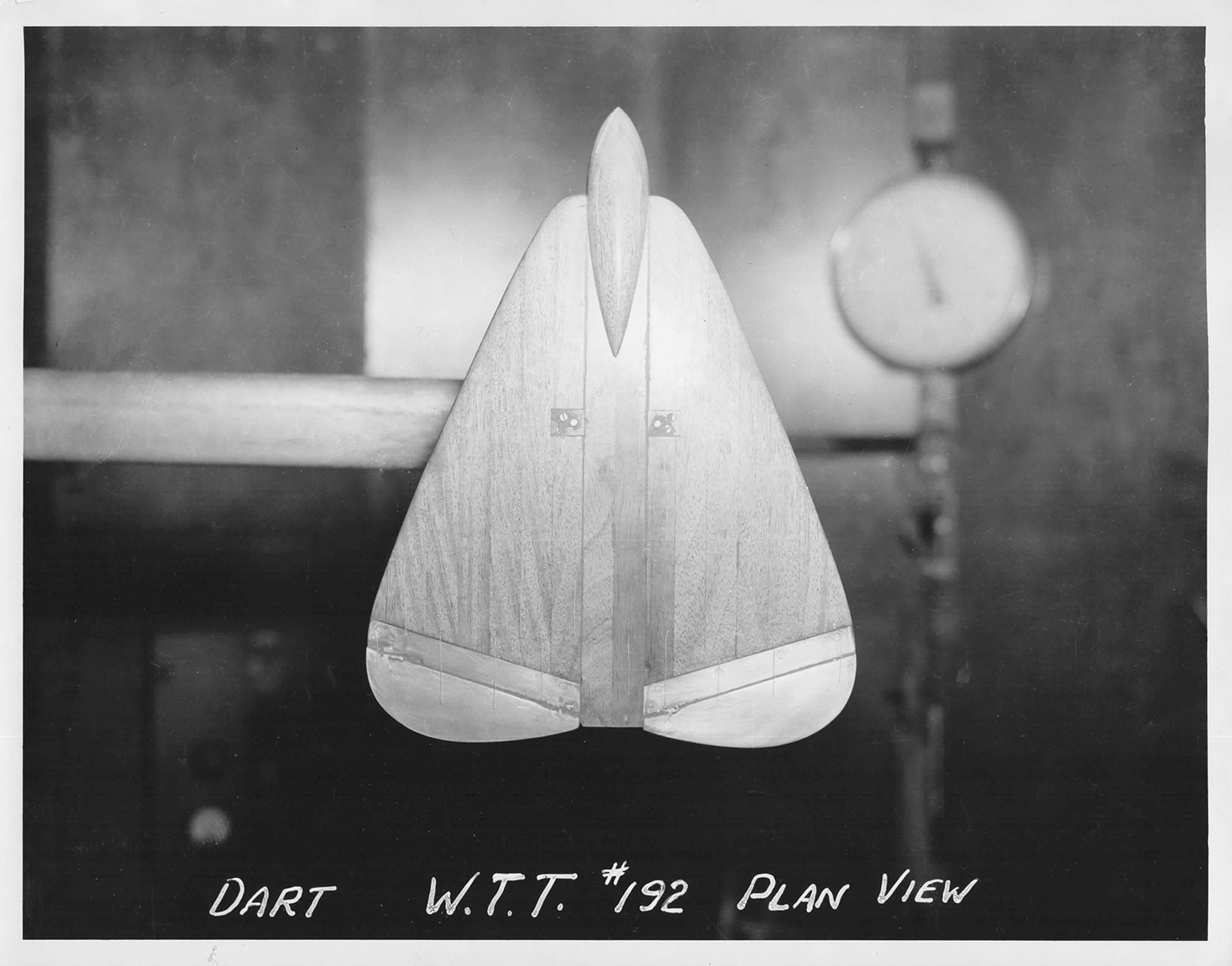

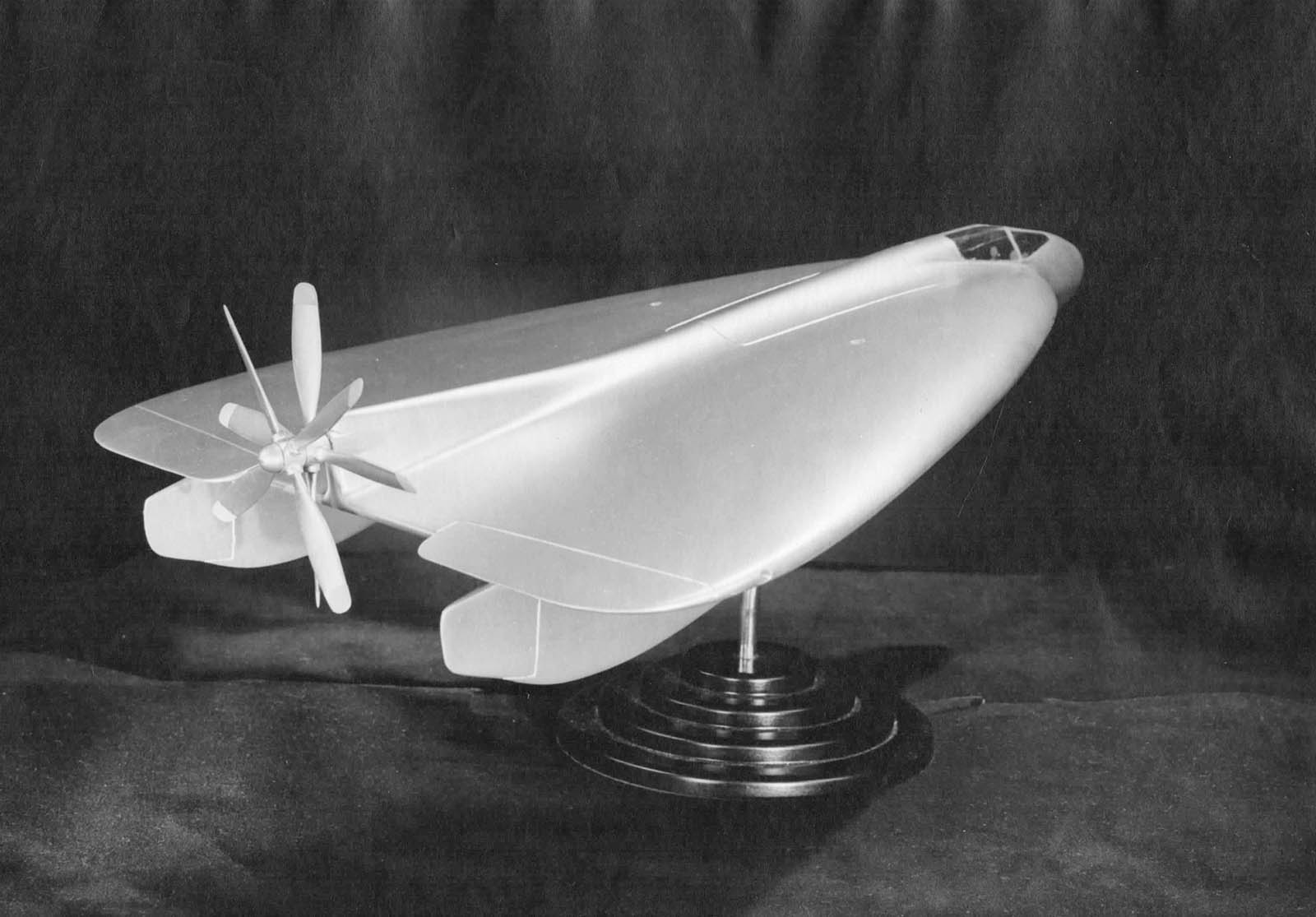

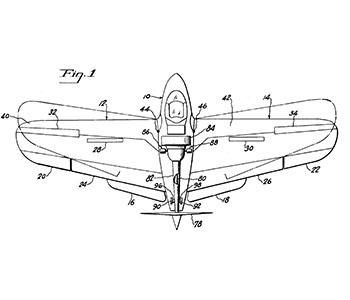

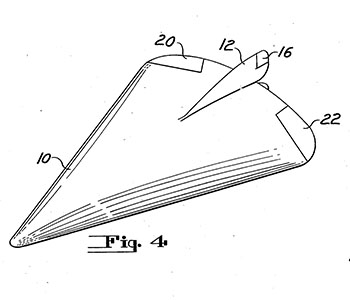

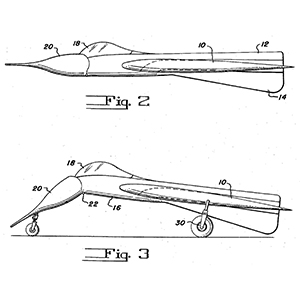

Gluhareff’s design incorporated a delta wing with a 56° sweepback angle and no tail surfaces. He chose these characteristics because they produced a considerable delay of the compressibility effect, which limits an aircraft’s maximum airspeed. On the trailing edge of the delta wing were “flippers” as he called them (now known as elevons) for roll and pitch control. The rudders on the ventral fins underneath the aircraft provided directional control. Propulsion was provided by a piston engine driving a dual, counter-rotating pusher propeller. Michael named his aircraft “The Dart” after its arrow-tipped shape.

While Igor was impressed with Michael’s delta wing aircraft design, he was also focused on transforming the Sikorsky Aircraft Company into a helicopter business, so his response was that the company did not have the capacity to pursue development of another aircraft type. Igor agreed however that he would be willing to allow Michael to continue development of The Dart as long as another company performed the actual work of building the aircraft. Michael approached Roger W. Griswold, president of Ludington-Griswold Inc. of Saybrook, Connecticut, about being a partner and Roger agreed.

The story of The Dart continued through the early 1940s, as Michael and Roger tried several times without success to find customers for The Dart. An article in the March 1979 issue of Aviation Historian explains how, during the time of these rejections, Griswold met with aerodynamicist Richard T. Jones of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) to discuss Gluhareff’s delta wing design. Jones was so impressed that he created a proposal for NACA to test the high-speed benefits of swept wing and delta wing designs on experimental aircraft. He presented his plan to NACA’s Director of Research, George W. Lewis, and funding was quickly approved. What followed was the construction of multiple swept wing and delta wing aircraft, including the Bell L-39, Bell XS-2, Douglas D-558-2 Skyrocket, and the Convair XF-92A, which eventually became the F-102 Delta Dagger. By 1946, aircraft manufacturers like Convair were making considerable progress in developing delta wing aircraft with no knowledge of Michael Gluhareff’s historical contributions to their design.

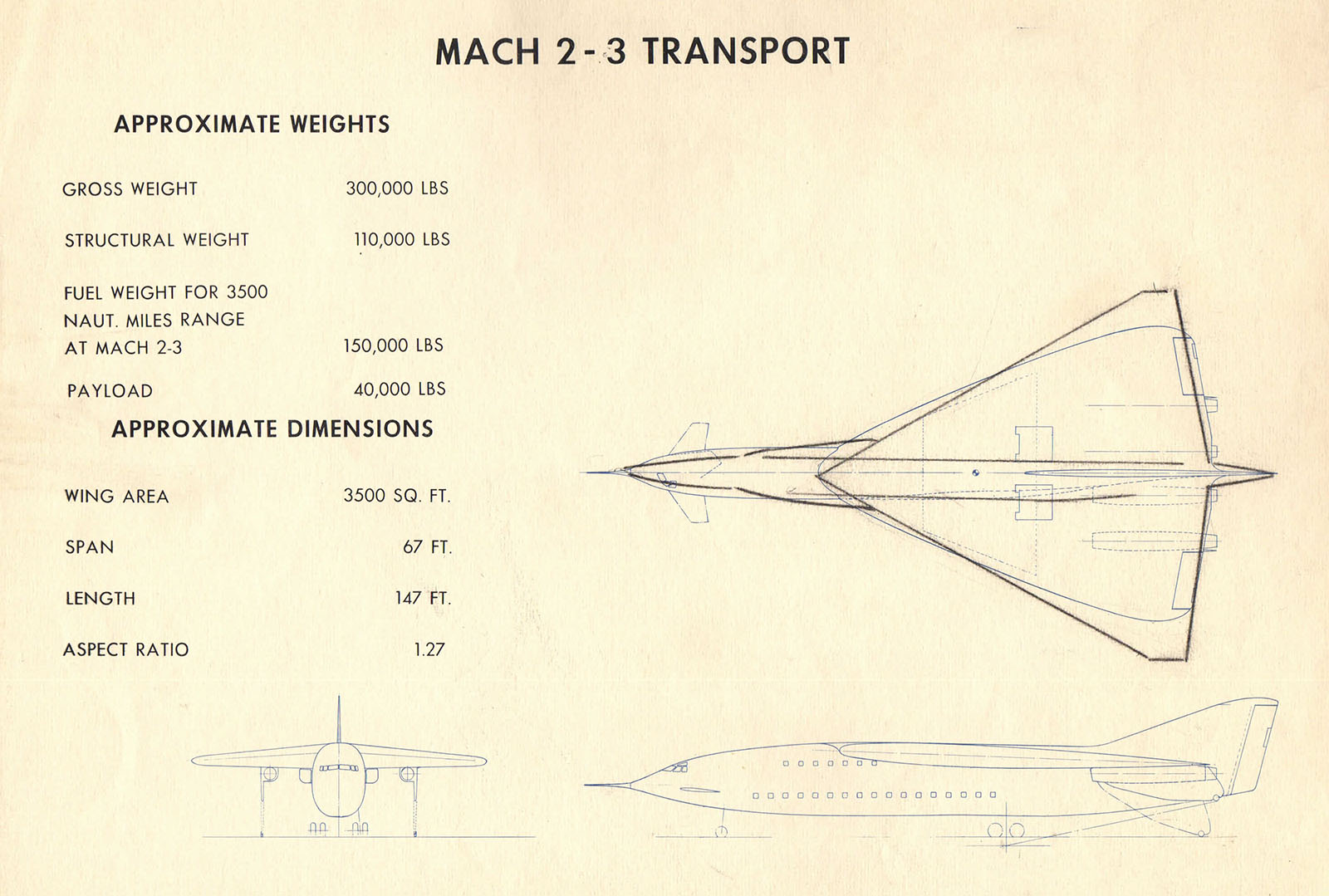

During the 1950s, Michael Gluhareff made two more attempts to develop a delta wing aircraft, but this time as part of the Sikorsky Aircraft Company. In 1951, the Sikorsky Aircraft Company proposed a high-speed, vertical takeoff and landing aircraft called the Sikorsky S-57 for a U.S. Army “convertiplane” competition. The design of the S-57 was heavily based on The Dart, with the inclusion of a retractable, counter-balanced single rotor blade for vertical flight. Then in 1959, the Sikorsky Aircraft Company proposed a Michael Gluhareff-designed Sikorsky SuperSonic Transport (SST) aircraft capable of Mach 2.5 speeds at 50,000 feet altitude. An article in the May 4, 1959 issue of Aviation Week described this aircraft and explained that the Sikorsky Aircraft Company was looking for commercial airline customers. Unfortunately, Sikorsky did not win the U.S. Army’s convertiplane competition and there was no known customer interest in the Sikorsky SST, so this was the end of Michael Gluhareff’s development of the delta wing. Gluhareff’s legacy, however, lives on in the delta wing supersonic aircraft that have followed, including the Concorde. Today, Michael’s balsa wood model of The Dart, which he constructed in 1939, is found at the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum. In addition, he holds three U.S. patents for the design of delta wing aircraft.

The High-Altitude Sailplane

In another side-project from his role as chief engineer at the Sikorsky Aircraft Company, Michael Gluhareff continued his early interest in designing sailplanes and gliders. In a partnership with the Pratt, Read, and Company, Michael designed a high altitude, two-seat sailplane for the U.S. Navy called the PR-G1. On March 19, 1952, the PR-G1 flew at a world record altitude of 44,255 feet. The PR-G1 sailplane is on display at the Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington.

Engineering Manager and Retirement

In 1957, Igor Sikorsky retired from the Sikorsky Aircraft Company, and Michael Gluhareff took over his role as engineering manager. Gluhareff held that role until 1960 when he also retired but, like Igor Sikorsky, he continued with the company as a consultant. During this time, Igor and Michael worked together on their last major aircraft design, the helicopter “crane” concept known as the S-60 Skycrane.

Michael once affectionately described his hiring in 1924 by Igor Sikorsky as “the beginning of an argument that lasted 30 years.” With their offices located next to each other, rarely a day went by when the two were not together arguing over some aspect of an aircraft’s design. The two held the utmost respect for each other both personally and professionally, and they had a long-lasting friendship.

Former Sikorsky President Bill Paul remembers when he first met Michael Gluhareff when Paul joined the company in 1955 as an engineering aide. “He was a legend with a very gentle soul. He demanded respect because he was a quiet, confident person with a huge history.” In his engineering aide role, Bill Paul was responsible for measuring vibration levels onboard S-56 helicopter test flights, and while doing so during one flight, he solved a peculiar vibration issue that the company had been investing substantially to investigate. This accomplishment endeared him to Michael and the two kept in touch as Bill’s career advanced. After Michael retired and became a consultant in 1960, the two met occasionally for tea and he would give Bill mentoring advice. “Here is a wise man listening to you,” Bill reflected. “It gave me the confidence I could talk with anybody.”

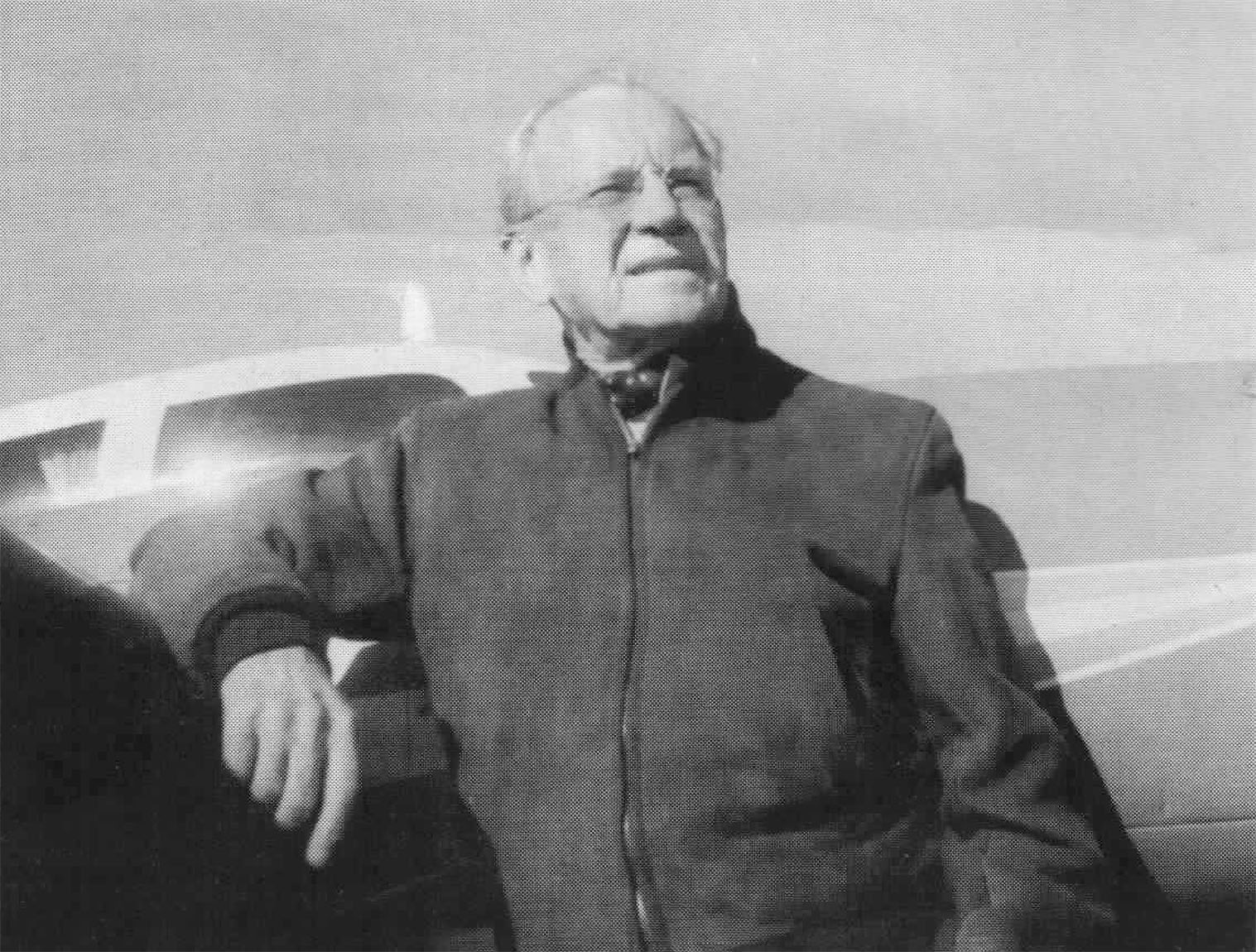

Michael Gluhareff retired from his consultant role in 1964, culminating a career of over 40 years with the Sikorsky Aircraft Company. His legacy as an aviation pioneer includes his remarkable GS-1 wing design, used on almost all Sikorsky airplanes, as well as his key role as chief designer of Sikorsky airplanes, flying boats, and helicopters. His aviation pioneer legacy extends beyond his career at Sikorsky with his design for the record-breaking PR-G1 high altitude sailplane and his invention of the delta wing for high speed and supersonic flight.

Recognition that Michael Gluhareff received during his career for his aviation achievements included being named a fellow of the Institute of Aeronautical Sciences in 1942, awarded a certificate of merit by the American Helicopter Society in 1948, and winning the Klemin Award for his contributions to the helicopter industry in 1954.

A particular recognition that Michael held in highest regard however was one he received in October 1964 from Igor Sikorsky at a lunch meeting of the Association of Russian Fliers of the United States. During his speech, Igor called Michael “one of the 20 foremost designers in aviation history.” Michael said that afterwards, he asked Igor if he really meant it, and Igor replied in a lighthearted fashion that reflected their relationship, “Michael, I’ve changed my mind. You’re not one of the 20 best, you’re one of the 12 best designers in aviation history.”

Throughout his aviation career, Michael Gluhareff was granted a total 17 United States Patents for his inventions, including tailless aircraft, helicopter rotor blades, and the remarkable supersonic delta wing aircraft known as “The Dart”. Strangely enough, he found that his innovative GS-1 wing design was not patentable.

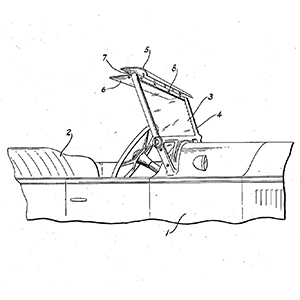

Gluhareff’s first patent, for an aerodynamic convertible automobile windshield to direct airflow above vehicle occupants, and prevent turbulent air from entering the cabin.

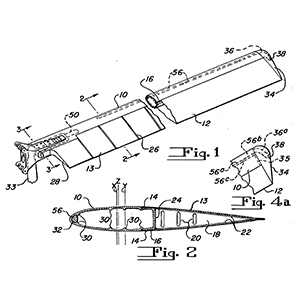

Design of a pusher propeller-driven, tailless airplane with a forward swept wing and accompanying flight control surfaces to provide stability and control.

A structure to prevent helicopter rotor blades from drooping beyond a point when the rotor is stationary or slowly moving, but allow drooping when rotating at operating speed.

A stabilizer for a helicopter that is adjustable to provide pitch stability while in forward flight and a vertical fin surface while in hover.

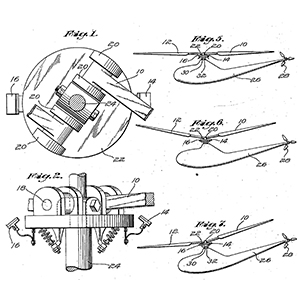

A single-bladed rotor with both static and dynamic counterbalancing to compensate for drag effects. This concept was tested on a Sikorsky R-4 helicopter in 1948 and was part of the Sikorsky S-57 Convertiplane design.

Gluhareff’s invention of a supersonic delta wing aircraft, also known as The Dart. His design incorporates a highly-swept delta wing with low parasite drag and high stability at both low and high speeds.

Design of a metal helicopter rotor blade containing a means of adjusting its chordwise balance, and therefore improve its aerodynamic performance.

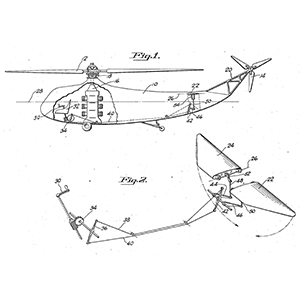

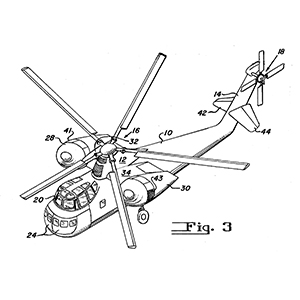

Design of a helicopter with engines mounted to fixed wings to provide an unobstructed cabin and cargo compartment. This design was used for the Sikorsky S-56.

Design of a supersonic delta wing airplane with a movable nose to improve the pilot’s forward visibility during the landing approach. This concept was used in the design of the Concorde supersonic airplane.

The large and powerful Sikorsky S-56 was Sikorsky’s answer to the U.S. Marine Corps’ request for a shipboard helicopter that could carry heavy loads on amphibious assaults.

Like Igor Sikorsky, Michael Gluhareff was a true aviation pioneer. As Sikorsky’s Chief of Design, he collaborated with Igor Sikorsky on the design of the company’s aircraft. In his spare time, he invented the delta wing for supersonic flight.

Sikorsky Aircraft was created by aviation pioneers during their early years in America.