Sikorsky Archives Opens New Home at Sacred Heart University

On 12 October 2023, the Igor I. Sikorsky Historical Archives formally opened its new home at Sacred Heart University (SHU) in Fairfield, Connecticut.

Sergei remembers visits to the Sikorsky home by the Lindbergh family, Colonel Jimmy Doolittle, Captain Eddie Rickenbacker, and many other aviation greats. From 1939 onwards, he followed the development of the first successful Sikorsky helicopter, the VS-300. He later flew in the pioneering rotorcraft with his father at the controls.

During World War II, Sergei served in a joint U.S. Coast Guard/U.S. Navy/Royal Air Force helicopter squadron at Floyd Bennett Field, Brooklyn. He participated in the development of the earliest helicopter rescue hoists and flew on some of the first helicopter search and rescue missions near the end of World War II.

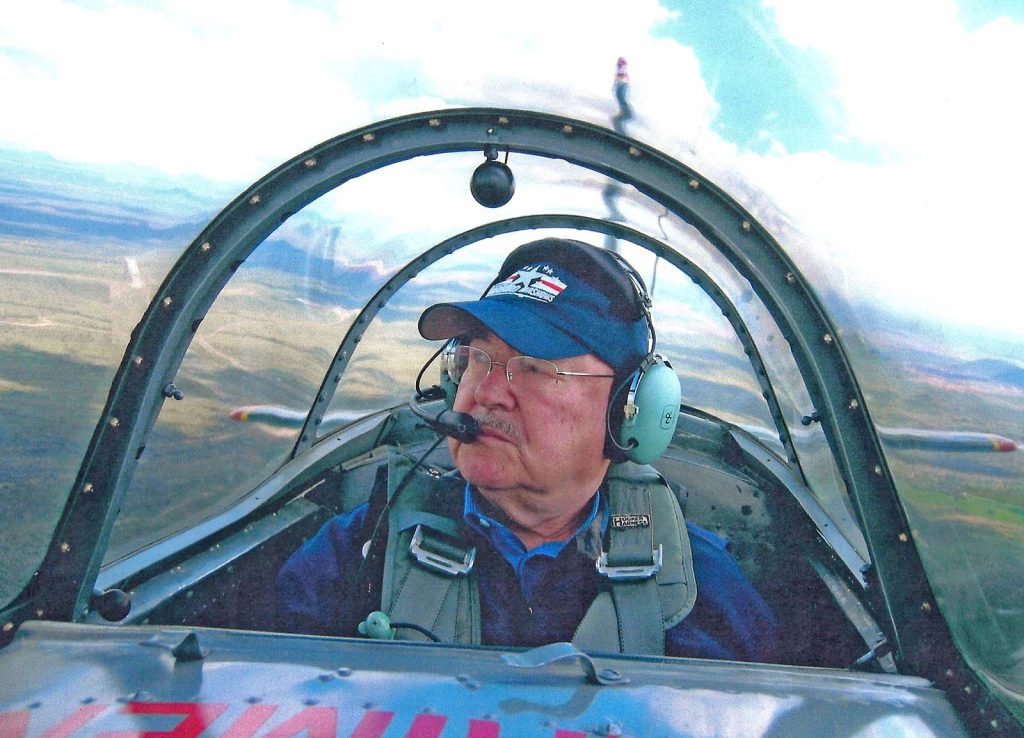

Following World War II, Sergei studied at the University of Florence, Italy. He joined United Aircraft Corporation in 1951. Twenty-four years of international helicopter marketing and manufacturing assignments followed, during which he lived in Germany, Japan, and France. Sergei flew many types of aircraft for business and pleasure in Europe, at one time or another holding American, Italian, French, German and Swiss pilot licenses. After the end of production of the Sikorsky CH-53 transport helicopter for German Army Aviation in 1975, he returned to the Sikorsky Aircraft headquarters in Connecticut.

Sergei Sikorsky retired from Sikorsky Aircraft as Vice President Special Projects in 1992. He remains active as an aviation consultant. Sergei Sikorsky has received numerous aviation honors and awards and is fluent in French, German, Italian and Russian as well as English. Sergei’s hobbies include flying, aviation history, target shooting, painting, and classical music.

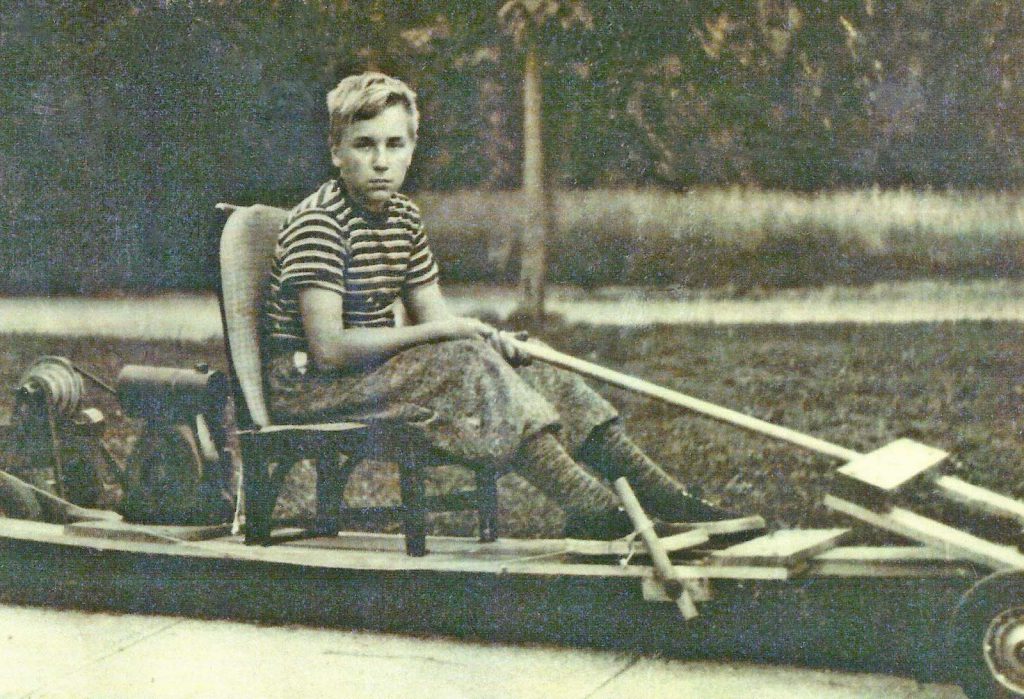

SERGEI: Growing up in the Sikorsky household was exciting. It was wonderful, especially if you loved aviation as I did. I think my love for aviation started by simply watching and listening as father talked shop with his cohorts. I don’t remember anything of the Long Island period. The start on the Utgoff farm, the building of the S-29A, and the gift of five thousand dollars by the great Sergei Rachmaninoff that enabled the move to Roosevelt Field were all before my time. I was born in 1925, the same year that saw the renaissance of the company when Mr. Arnold Dickinson and some Fitchburg friends refinanced the company. They moved it to College Point, across the bay from LaGuardia Airport in 1926, when I was one year old. Mr. Dickinson was President and Dad was Engineering V.P. It was there that the S-38 was born. First flight was in June of 1928. It was an instant success, and orders started pouring in.

In the spring of 1929. Back in 1928, the first batch of ten S-38s sold out within days. A second batch, about twenty aircraft, sold “off the floor.”

It became apparent that the rented factory space at College Point was too small to satisfy the growing demand for the S-38. In 1928, Dickinson and his Fitchburg investors decided to build a new factory. The Stratford location was chosen by Dad; it was on the Housatonic River, close to Long Island Sound and across the street from a small airport.

The new factory was finished in early 1929, the family moved from Long Island to Lordship, then a tiny village some two miles from the factory. We were a five-minute walk from the beach on Long Island sound. Today, it is still called “Russian Beach.” The little house that the family rented in Lordship still stands today.

Another reminder of those early days is a framed picture hanging in my father’s office. It was one of his favorites. It is an advertisement from the July 1929 issue of the venerable “Aero Digest.” In the ad Sikorsky’s sales agent, Curtiss Flying Service, regrets that the success of the S-38 has led to a three-month wait for delivery of the aircraft.

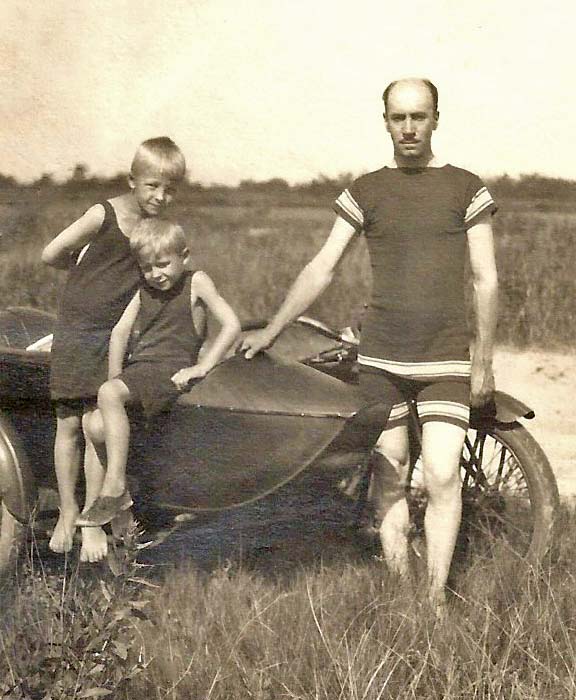

I must confess that I was too young to notice the benign purchase of Sikorsky Aircraft by United Aircraft in July 1929. As a four-year-old, I was probably too busy on the “Russian Beach” that summer. Father was happy with the move, it allowed him to concentrate on engineering.

United Aircraft appointed Eugene Wilson, a retired Naval aviator and United executive, to be President of Sikorsky. The early investors and the Fitchburg group reportedly made a reasonable profit. Mr. Dickinson was nominated to the United Aircraft Board of Directors.

I still remember fragments of a weekend visit to the Dickinson home, and Mr. Dickinson inviting us for a motorboatride on a huge lake. We tied up to a pile of concrete and rocks in the middle of the lake and went swimming. There, Mr. Dickinson told me that “cannon balling” was not the proper way to dive into the water. After some ten minutes of gentle persuasion, much to the amazement of my parents, he and I were diving, head first, into the water. Thank you, Mr. Dickinson!

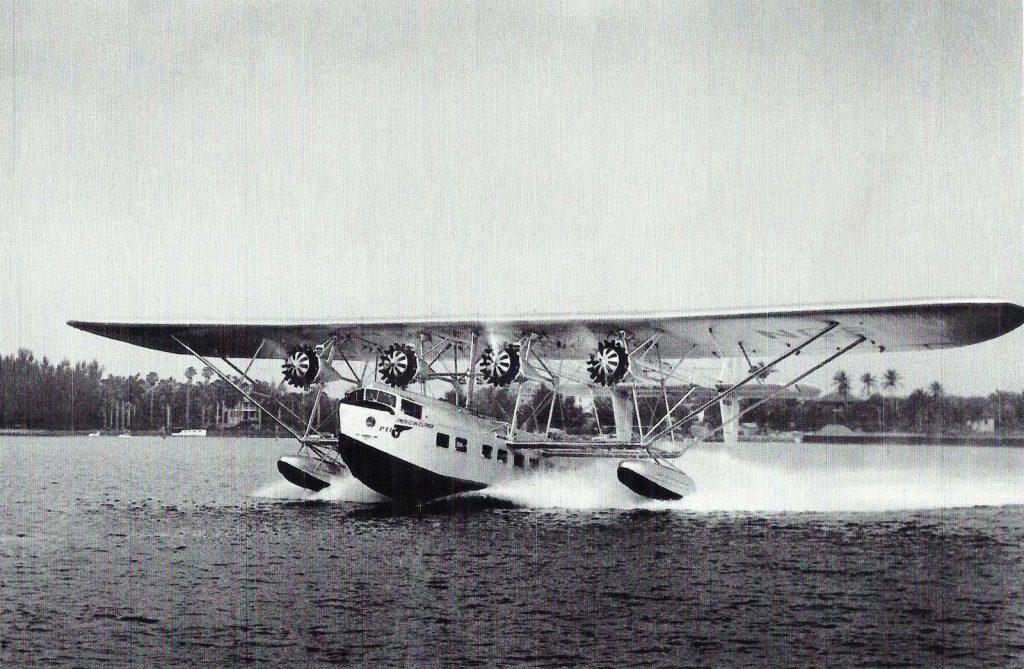

In 1931, I witnessed the public roll-out of the S-40, the first of Pan Am’s “Clipper Ships.” At the time, the engines were started by hand-cranking. I still remember the mechanics climbing the struts between the lower and upper wings. After reaching the four engines, each two-man team started cranking the inertia starters. The noise is still music to me; the low whine growing into a high-pitched scream, the sharp bark and roar as the engine came to life, belching clouds of blue smoke. Some years later, Dad reminded me that I asked him “When I grow up, can I get a job climbing up the struts and starting the engines?” Then, some bum invented the electric starter and my dream job went away.

In the 1930’s, I continued my love affair with aviation. I was inspired by visits to our new Long Hill home by aviation legends. The S-40 and S-42 design process resulted in several “working lunches” in our home with father hosting Charles Lindbergh, Juan Trippe, and Andrei Priester of Pan Am.

Several times, Dad had to phone our local two-man police force to clear reporters huddled on the end of our driveway, waiting to steal a photo of Lindbergh. I remember one summer afternoon, date unknown. A rather sleazy type crouching behind our fence called out to me. “Hey, kid. You live here? Can you get in the house? I answered “Yes”. He passed a huge press camera, with flash gun, over the fence and said “Sneak in the house, aim at Lindbergh through this sight and push this button. I’ll give you five bucks for the job.” Even though, to me, five bucks was really serious money in those days, I said “No thanks!”

There were many more guests for lunch in the 1930’s as brother Nicky and I grew up, making rubber-band powered model airplanes. I continued to be fascinated by our visitors. They included such aviation legends as Jimmy Doolittle, Eddy Rickenbacker, and many others. But the most colorful was Roscoe Turner, even though brother Nicky and I regretted that Gilmore, his lion cub copilot, never came to visit.

It was then that I discovered my father’s interest in mountaineering. Over the years he had followed the attempts to climb Mount Everest. I remember how closely he followed the press accounts of the 1933 flight by two specially built Westland aircraft over the “top of the world” and studied the photographs they published of the majestic peak of Mount Everest. No, there was no sign of Mallory and Irvine.

During those early days, father bought a used telescope. He had a small shed built for the telescope, complete with sliding roof. We spent many evenings observing the stars. My favorite was the moon; the ‘scope let me “wander” from crater to crater. I remember Dad making an uncanny prediction one night. He said “probably, I will not see man walk on the moon, but almost certainly, you will.” A daring prediction in the early 1930’s became reality before the end of his life.

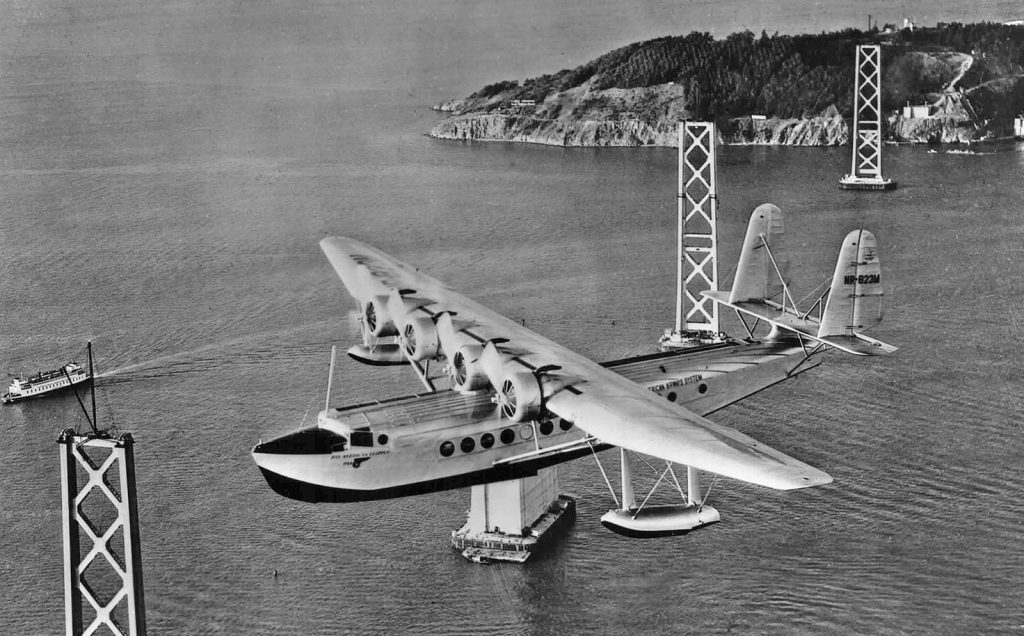

I remember an afternoon in 1934, when mother drove us to the Lordship lighthouse. We watched the S-42 pass overhead. It was the finish of a four lap, eight-hour flight around Long Island Sound, establishing eight world records. Like the dozens of cars parked there, we too, blew the car horn in celebration. Today, I can still hear the horns and the sound of that beautiful silver bird flying low over our heads. At home in Long Hill, my brothers and I continued to enjoy life, build model airplanes and feed a growing family of stray cats and dogs.

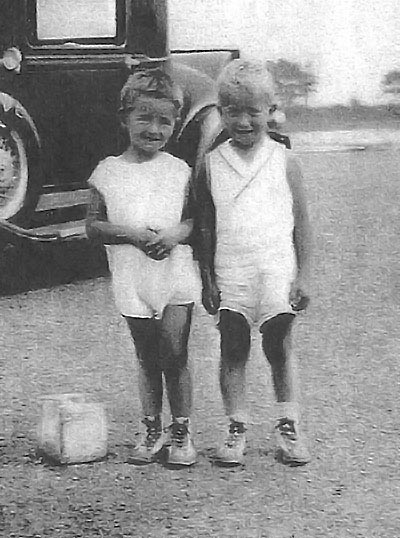

One Sunday afternoon, the Lindberghs with sons Jon and Land were our guests for lunch. While the grownups relaxed with after dinner coffee, we kids were playing outside. I don’t know how it started, but suddenly we were in a wonderful water fight with garden hoses and buckets full of water. Eventually, the grownups came out to investigate the noise, and the battle was over. The Lindberghs drove home, Jon and Land stripped and still wet, wrapped in borrowed beach towels.

1938 started rather sadly, with the bad news that Captain Ed Musick and the crew of Pan Am’s S-42 “Samoan Clipper” had been lost during a South Pacific survey flight. It was almost like losing a family member. He, too, had visited our home during the birth of the S-42.

In late 1938, father told the family that some crucial decisions lay ahead. The last of the Sikorsky flying boats, the VS-44s were being built, but no further orders were in sight. As children, we sensed the strain he was working under. For the past year, after a busy day in the plant, he would have supper and then retire to his “office” where he would work late into the night. He knew that Sikorsky Aircraft was in trouble. His solution was to move out of the airplane business and return to his first love, the helicopter.

I remember father made a rough sketch that summer. I was “hired” to build a balsa wood model from the sketch. I dressed it up with small rubber wheels from a local model shop. Perhaps four-five weeks later, I would get a new, slightly different sketch and promptly build a new, slightly better version. The designs were that of a small single-seat helicopter, not too different from the final version of the VS-300. Later, I learned that Dad used the models while “selling” the concept of the helicopter to his somewhat skeptical senior engineers.

In late December of 1938, Dad drove up to United Aircraft’s head office in Hartford. As he drove off, I sensed that something important was in the wind. Years later, I would learn that he went to Hartford for a very important meeting with Eugene Wilson, now senior V.P. of United Aircraft. The meeting resulted in the survival of Sikorsky Aircraft and the approval of an experimental helicopter program, designated the VS-300.

The transition from the flying boat to the helicopter was not an overnight decision. Dad’s first love was the helicopter. His first two aircraft, back in Russia, were helicopters. They didn’t work and he “temporarily postponed” the helicopter and turned to fixed-wing aircraft. However, in 1930, while busy with the design of the S-40, he still found time to write a memo to United Aircraft management, suggesting that United study the helicopter. Obviously, during all those years, the helicopter was very much alive in the back of his mind.

Another factor, sometimes overlooked, was the correspondence between Dad and Charles Lindbergh in the 1936-1938 timeframe. Researching those letters, one finds that Lindbergh was gently hinting that the era of the trans-ocean commercial flying boat was slowly ending. Knowing, firsthand, the warm friendship and respect each had for the other, it is obvious that those Lindbergh/Sikorsky letters were carefully evaluated.

I believe that my father knew that there was a good chance Sikorsky Aircraft would be absorbed into the rapidly expanding Chance Vought Corporation. There were no new flying boat contracts on the horizon. However, the helicopter program had given the company a lease on life. For Igor Sikorsky, in his words, “It was a chance to relive my life once again. To design a new aircraft without knowing how to design it. Then build it without really knowing how to build it. And then, climb aboard and try to fly it, having never flown a helicopter before!”

The spring of 1939 was tense. War clouds were gathering over Europe. Pratt & Whitney received huge engine orders from France and England. P&W had to expand production. In April of 1939, Chance Vought moved out of Hartford into the Sikorsky factory. I didn’t like the fact that the Sikorsky part of Vought-Sikorsky was squeezed into one hangar where the last flying boat was being completed. However, I had to admit that the Vought Corsair was an exciting, strangely beautiful aircraft.

The VS-300 made its first tethered flights in September of 1939, just as World War II started in Europe. Every so often, father would take me to the factory to see the VS-300 fly. When possible, I would ask to pilot the little helicopter trainer hidden in a corner of the hangar. While “flying” the trainer, I would dream of flying a real helicopter when I grew up.

Steadily, the helicopter was modified and improved. In May of 1941, mother drove the (now) four Sikorsky sons to an open field behind the factory, parked the car, and let us out. We joined a small crowd of photographers, reporters and employees and watched as Dad took off in the VS-300. He landed 1 hour, 32 minutes later, having established a new world endurance record for helicopters. The further development of the VS-300 is well documented elsewhere; and need not be repeated here.

I well remember Sunday afternoon, December 7, 1941. We were home. As usual, I was building a model airplane while listening to the Sunday afternoon concert of the New York Philharmonic. Suddenly, the radio switched to a male voice reporting that “unidentified aircraft had bombed Pearl Harbor.” The next day we were at war. Six weeks later, the XR-4 first flew, on January 13, 1942. In May, Les Morris flew the helicopter to Wright Field and the Army started evaluating this new and unusual aircraft.

Life suddenly became serious as the draft and military service came on the horizon. I started working in the factory while finishing high school at night and graduated in June 1942. In the factory, I worked in an experimental shop supervised by Al Krapish and “Scotty” Maxwell; both employees had started with Dad in the Roosevelt Field days. They told some wonderful stories about the early history of the company and aviation in general.

Al was a “weekend racing pilot” in the east coast air show circuit while working for Dad at Roosevelt Field. A crash ended his racing career, but he stayed with Sikorsky. “Scotty” was a tiny person, weighing possibly one hundred pounds soaking wet. I remember him telling stories about being the mechanic on the S-29A, after it was sold to Roscoe Turner. The stories were full of interesting flights and forced landings.

In the experimental shop, we started building a mockup of a small, two-place helicopter. The project number was S-50. I was drafted long before the mockup was completed.

While helping push the VS-300 out and back into the hangar for test or demo flights, greasing and cleaning it between hops, I met many interesting people. Captain H.F. Gregory, U.S. Army Air Corps, Director of the Army’s rotary wing research programs, was a frequent visitor, monitoring the progress of the YR-4 contract and, occasionally, flying the VS-300. Commander Frank Erickson, newly assigned to the Coast Guard Air Station, Floyd Bennett Field, escorted senior Navy people to Stratford to introduce them to the helicopter. On several occasions, I watched visits by R.A.F. delegations, often headed by a famed British autogyro test pilot, Wing Commander Reggie Brie, based In Washington as part of the U.K.’s Purchasing Commission. Dr. J. A. J. Bennett, former director of the Cierva Autogyro Company in England, became Resident Technical Officer at the factory. He returned to England after the war and designed the Fairey Gyrodyne. On several occasions, I watched Charles Lindbergh fly the VS-300.

As father mastered the helicopter, I was allowed to stand on the landing gear struts as he took off, hovered and then slowly flew me around the open fields behind the factory. Those flights were delightful adventures and I grew to love that wonderful little VS-300 nearly as much as Dad did.

After Pearl Harbor, all private flying was banned within fifty miles of the coast. Bridgeport Flight Service moved inland to Turners Falls, Mass. At the time, Jimmy Viner was a senior flight instructor there. He soloed me there in 1942.

In January 1943 Sikorsky Aircraft moved out of Stratford into the old Crane Radiator factory on South Avenue, in Bridgeport. Thick, rusty dust covered the floors and shelves. We shoveled for a week, wearing filters to cover mouth and nose. Then, YR-4 production jigs were put into place and the first helicopters started taking shape. About June, I received my formal draft notice. I quit Sikorsky and put in a bid to be inducted into the Coast Guard. CDR Erickson was quietly working on the formation of a Helicopter Development Group, to be based at Floyd Bennett Field. Other Sikorsky people were being called up, and some of them opted for the Coast Guard as well.

I had the chance to be flown several more times in the VS-300 with my father at the controls. By this time the aircraft had been modified with the addition of a passenger seat.

In September 1943 I was ordered to report to the Coast Guard Basic Training Center or “Boot Camp” at Manhattan Beach, N.Y. Somehow, I survived the training camp. In late December, I reported to CDR Erickson’s new command at Floyd Bennett Field, as he was receiving his first HNS-1’s (Navy designation for the R-4).

Most historians agree that 131 R-4 helicopters were built. They were operated by the U.S. Army Air Corps, the Coast Guard/Navy, the RAF and Royal Navy. The first production R-4 was delivered in May 1943 the last R-4 was delivered in June of 1945.

My Coast Guard career started, literally, with a bang. In the pre-dawn darkness of January 3, 1944, the U.S. Navy destroyer “Turner” blew up in a violent explosion. Though it was anchored off Sandy Hook, New Jersey, some twelve miles away, the shock wave hit our barracks, jolting us awake. The weather was horrible, mixed rain, snow and sleet driven by 30-plus m.p.h. gusts, visibility, a half-mile or less. All airports from Baltimore to Boston were shut down. At dawn, CDR Erickson volunteered to fly to Battery Park, picked up blood plasma, and flew it across the bay to Sandy Hook hospital, where the badly burned Turner survivors were being treated. As his HNS-1 (R-4) helicopter disappeared into the snowstorm, little did I know that I was witnessing history… the first life-saving mission by helicopter.

Duty at the Coast Guard Air Station was interesting and challenging. CDR Erickson wasted no time in setting up a pilot training program and a maintenance school for mechanics to service the growing fleet of helicopters. In the spring of 1944, we received a dozen RAF pilots and about thirty RAF mechanics. They had their own quarters at the Coast Guard Air Station but trained and worked side-by-side with us. They took delivery of several R-4’s in RAF markings, adding to the training fleet. As soon as they finished training, they returned to the U.K. and were replaced by a group of new students. After the war, a few Floyd Bennett graduates became helicopter test pilots, including S/LT. Alan Bristow, Royal Navy.

In April 1944 in far away Burma, new history was made by a U.S. Army Air Force pilot. LT Carter Harman flew his R-4 deep into Japanese held territory to rescue, one by one, the four survivors of a med-evac airplane crash. As CDR Erickson studied the mission report, he realized that the rescue helicopter needed a winch or rescue hoist. He described his idea to two talented petty officers under his command, Chiefs Oliver Berry and “Red” Lubben. Interestingly, Red was one of the select crew that had worked on the VS-300 before being drafted. The hoist program was not authorized, hence not funded.

Using scrap material, the two Chiefs improvised an electrically powered hoist. It was used to develop rescue procedures. The hoist was under powered and woefully slow, but the concept generated great interest. We tested several versions of the sling, and developed a float for the hook so that it could be easily grabbed by a person in the water. We tried hoisting a Stokes litter fitted with a cover to shield the occupant from rotor down wash. I enjoyed being hoisted with a sling, but being hoisted while in a closed-up stretcher, with just a tiny window in the lid, was not much fun. We developed a small basket just big enough to seat a man. The rim had balsa blocks for floatation. It could be hooked to the rescue hoist hook by an overhead ring. Today, it is called the “Erickson Basket”.

Dad and Michael Gluhareff visited the base in August 1944, and father was (briefly and carefully) hoisted a few feet by a HNS-1 piloted by CDR. Erickson. In September, Erickson was “loaned” two hydraulic motors by the Vickers company. The hoist was rebuilt literally overnight by Berry and Lubben and the Vickers pump installed. The first tests early the next morning showed a dramatic improvement in hoist speed and load capability. Quite honestly, I felt a lot happier being hoisted with the new, high speed hoist. It allowed the helicopter to accelerate from hover to best climb speed much faster. It just felt better, not only for the pilot.

Engineers from Wright Field, Sikorsky Aircraft, Kellett Aircraft and even the Royal Navy visited Floyd Bennett to inspect the hoist and watch the flight demonstrations. Colonel Gregory ordered a dozen hoists. They were built at the Air Station. In late October, the hoists were delivered to Wright Field, where a Coast Guard technician helped install the first hoist in one of the USAAF R-4’s.

Memories of my Coast guard career include a few highlights. They include a cross country flight to the Navy Test Center at Patuxent River, Maryland. The next day, we demonstrated the helicopter, and the hoist, to the Senate Armed Services Committee and its Chairman, then Senator Harry Truman.

Once, I was signaling a float equipped helicopter to land on a grass patch. It hit hard and went into ground resonance. I remember it bounced forward, then back. As it bounced forward again, the main rotor blades hit the ground, about ten feet in front of me. I froze as blade tip weights, bits of rotor blade ribs and spars flew all around me. By a miracle, nothing hit me, though several cars parked a hundred feet away had windshields shattered by the flying debris.

By the end of 1944, the war in Europe was clearly turning in favor of the Allies. In December of 1944, the last British pilots finished training. On 14 December, eleven British R-4s took off from Floyd Bennett and flew off to Norfolk with the last of the pilots, crew men and luggage. They embarked aboard a British aircraft carrier and sailed to England.

The sixth Coast Guard pilot class reported for training on Jan 2, 1945. We didn’t know it would be the last class. In Washington, Coast Guard Headquarters went through a major reorganization. Several key slots went to “flying boat” executive officers, hostile to the helicopter. When the helicopter class finished training in February, all training stopped. CDR Erickson was replaced by CDR Hesford, and the Air Station was re-designated as a seaplane base. CDR Erickson and his helicopters became low priority guests at Floyd Bennett.

With the end of the war in sight, and huge stocks of fuel now surplus due to the end of flight training, a unique opportunity arose. One kind officer offered to give me some unofficial flight training. He was bored, I was happy. I would pull, then replace a few spark plugs. Then, we would fly out on a maintenance check flight. Often, we used a small training field on Far Rockaway. I then was soloed in the HNS-1 (R-4).

The helicopter became very popular at the many local war bond rallies. Thanks to the low downwash it generated, it could be hovered very close to the crowd line while demonstrating the rescue hoist. We flew many such demonstrations. I remember one particular bond rally on a Sunday in May 1945. LT Stew Graham and I flew to LaGuardia field and did several hoists that afternoon. It was my first close-up look at the B-29 Superfortress, the F-80 jet fighter and a pleasant chat with Guest of Honor Jackie Cochran (Pioneer woman aviator – founded woman’s Air Force Service Pilots. Enshrined in the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1971 – ed).

Meanwhile, during that spring and summer of 1945, CDR Erickson and LT Graham operated off Block Island, testing the first concept of what was to become Sonar, or submarine detection by helicopter. The end of the war in Europe in May, followed by Japan’s surrender in August 1945 was followed by a general slow down in activity. Several senior officers and enlisted men were discharged back into civilian life, and the process continued.

On 23 December 1945, I participated in a search and rescue mission. Local police phoned; three young boys went duck hunting in Jamaica Bay two days earlier and had not returned. In those days, before the creation of JFK (airport) that would fill half of the bay, it was a pretty big body of water with a few small, scattered islands. It was a bitterly cold evening, but the duty pilot (I have forgotten his name) and duty aircrew (me) took off. In the twilight, we started a search pattern. Some fifteen minutes into the flight, we noticed a tiny campfire on one of the islands. We landed and I walked up to the fire. Two tiny, frightened boys, aged 7 and 9, ran up to me and grabbed my legs. They sobbed, as they told me that their older brother had accidentally shot himself. I checked the site, and found the body of the older brother, mutilated by a shotgun blast to his stomach. I strapped the two boys into the copilot’s seat of the R-4 helicopter, made the pilot promise to return for me. He did, and we made it back as total darkness set in. Following our description, the police retrieved the body later that night. The rescue of those two little boys is still fresh in my mind.

One month later, in January 1946, CDR Erickson and I flew to the Bridgeport plant. There, in front of Dad and many Sikorsky employees, Erickson and I made what would be my last demonstration of the hoist with its inventor at the controls.

I was discharged one month later in February of 1946.

After returning to civilian life. I got my private pilot license in August 1946. During my various assignments for Sikorsky Aircraft through the years, I have enjoyed flying a great variety of European and American aircraft, both for business and for pleasure.

On 12 October 2023, the Igor I. Sikorsky Historical Archives formally opened its new home at Sacred Heart University (SHU) in Fairfield, Connecticut.

Sergei Sikorsky recollects his early life growing up in the Sikorsky household during the era of Sikorsky flying boats and helicopter innovation.

The evolution of the Marine Corps’ CH-53K King Stallion heavy lift helicopter beginning with the Sikorsky S-56 in 1953.

A flight demonstration of Igor Sikorsky’s VS-300A helicopter at Bridgeport, Connecticut in April 1942 started an air-sea rescue revolution in the U.S. Coast Guard.

When Igor Sikorsky first flew his VS-300 helicopter on September 14, 1939, he made vertical flight discoveries that shaped helicopters to this day.

The United States Coast Guard and Sikorsky Aircraft celebrated two significant events in 2016. One century of United States Coast Guard aviation and the 127th birthday of Igor Sikorsky.

During Igor Sikorsky’s early years in America, he struggled to develop a successful aircraft company. That all changed with the S-38 aircraft.

Igor Sikorsky’s inventive genius was complimented by his human compassion, humble personality, and strong spiritual approach to life.