Sikorsky Archives Opens New Home at Sacred Heart University

On 12 October 2023, the Igor I. Sikorsky Historical Archives formally opened its new home at Sacred Heart University (SHU) in Fairfield, Connecticut.

Art: If you would, I always like to start these interviews by asking people, how did you get involved in aviation and where did it all start?

Dan: I realized that I was going to be drafted in 1951 due to the Korean Conflict. In January of 1951, I volunteered for the Air Force. I was sent to Whitehall Street in New York and from there, I was in the first squadron to open up Geneva Air Force base, which was a U.S. Navy base that was closed. It was a huge naval facility during World War II that was closed down and with the influx of the Korean volunteers, the Air Force took it over and it became a basic training base for people inducted on the East Coast.

Art: Where was it?

Dan: Geneva, New York.

Dan: You start with an incoming interview. The interviewer may have only been in the service six months earlier but to me, he’s a big guy. He’s looking at some paper and he says to me, “I think you should be a heavy equipment operator.” I said, “When I was a kid I always built airplanes. “As soon as I said airplanes the guy said, “Okay, you’re going to go to Aircraft and Engine School [A&E].”

Art: There you go.

Dan: My course changed. That directed me. The next step was a train ride to Wichita Falls, Texas, to the huge A&E training base that the Air Force had there. We were organized in squadrons. Each barracks was two stories with double bunks top and bottom and we constituted a squadron. The school was going 24 hours a day at least five days a week, I’m not sure about six days but five days a week. As one squadron was arriving in the back end of the building, the other squadron was moving out, and this continued for about three months. We had all the basic aviation studies to be A&E mechanics.

Out of the class of roughly a 150 people, I was one of three people picked to attend Sikorsky Helicopter School.

Art: Really?

Dan: I’m beginning to think fate was on my side and I was sent to San Marcos, Texas. They had a school and a hangar and they taught us on the H-5D, a model of the S-48 series Sikorsky helicopters.

This is the one that still had fabric covered main rotor blades and very primitive wooden tail blades. Bicycle chains connected sprockets for rotor control. There was no servo system. It was all mechanical linkages and sprockets. Then you had a combination of cabling and bungees connected to the cyclic and collective controls in the cockpit.

They worked the same way as a servo. You move the collective and the bottom sprockets lift everything else and you move the cyclic and they did the same thing. For the tail rotor drive system, it had a universal joint that came out of a car that changed the angle of the drive from the transmission down, out to the tail rotor.

I went through this school and now we’re all excited. We get out of helicopter school, we’re going to go in to Search and Rescue, and we could go any place in the world. Wherever the helicopters were, we would go. Well again, we’re a class of about 20 or 25 people and time comes to get our assignments. Again, out of this class of 25, two people, myself and another guy get picked and where do we go?

To a squadron maintaining Sikorsky helicopters on that same base and I said, “Oh, my God I’ll never get out of Texas.” I was assigned to a maintenance squadron that maintained Sikorsky helicopters for training Air Force pilots. Now you have to remember, in those days the Air Force was the primary trainer for all Army and Air Force helicopter people. The Army at that time was limited to the Hiller Raven H-23, the Bell H-13 Sioux helicopters and the Piper Cub. We had hundreds of Piper Cubs that they used for pilot training. We had H-13s and H-23s and in the middle was the Sikorsky, the big guys. We had H-5s there to begin with.

Art: You’re working on just the Sikorsky aircraft?

Dan: I’m working on just the Sikorsky models. We started on the H-5 series and then later we got our first H-19A (S-55s). That was powered with the R-1340 Pratt & Whitney engine, an underpowered machine, and it was delivered with these monstrous heavy metal floats installed with wheels in the floats. You were lucky to go 60 miles an hour with any kind of wind. We eventually took the floats off and conducted the training with wheeled landing gear only. Then about the end of 1952, in fact, some of you may remember an associate named Dan Ulisnik?

Art: “Harold Ulisnik”?

Dan: Harold Ulisnik. Well, we called him Dan though. He was in the Air Force unit with me. We were both sergeants and crew chiefs.

He was part of a crew on one aircraft, I was on another. Eventually around the end of ‘52, we were assigned to go to school at Sikorsky. We got TDY orders and came to Bridgeport and we went to school on Railroad Avenue where they had the service school. A fellow by the name of Jim Sanders ran the service school. For your information, Jim Sanders was probably the initial tech rep for Sikorsky, going back to the 1927 fixed wing aircraft. I did a little history on field support and he came out as the first one.

We went to school there and were trained on the H-19B, which had the Curtiss-Wright R1300 engine in it. That engine had about 800 horsepower and it made a big difference in the performance of the H-19. It had a hydraulic clutch instead of the centrifugal clutch. I went to the school and I must say in those days in Bridgeport, if you were in uniform, the whole city was open to you. Those were the days when Thursday night was a big night downtown, people got paid. There was the Barnum Hotel and there was Walgreens, and many more stores like the five and ten department store. Everyone was very respectful and fun to be around.

It was a good experience, and I was glad that I could train in the Sikorsky Service School. I went back to San Marcos and we continued our maintenance work. All of a sudden, a requirement came out for three mechanics and one pilot as a team to be dispatched to Saigon, Vietnam, then French Indochina.

Our assignment was to be part of the Military Defense Assistance Program to assist the French in the introduction of the H-19. So many of us volunteered for that assignment, that the Sergeant Major, after he screened all of us, put the names in the hat and lo and behold, the first name pulled out of the hat is mine. Again, something is guiding me to Sikorsky.

That’s right, pulls my name out of the hat along with two others by the names of Callahan and Bill Wright. The pilot was Captain Good who was assigned on his own.

We gathered together at Travis AFB in California around June of ’53. We went out there to get transportation to Saigon. We boarded a C-54, [laughs] for the long ride across the Pacific to Manila, and then eventually to Saigon. We landed at Tan Son Nhut Air Force Base. At that time Vietnam was still under French control. I looked around and I saw WWII Grumman Bearcats, and Hellcats, and B-24s, and German high-wing single-engine aircraft. All of this history was there.

We land and we go to the Military Assistance Program Office in Cholon, which was the Chinese section of Saigon, and there was the administrative group. Now, there were about 100 of us picked for all disciplines, propeller, engine, aircraft, helicopters, weapons, whatever. We all gathered there, got our assignments, and went on from there.

I was told that the U.S. government was sending one million dollars a day in equipment to the French. That was in lieu of sending troops because U.S. Sec. of State, John Foster Dulles, was approached by the French to put troops in, but there were 500,000 U.S. troops in Korea. The U.S. couldn’t afford any more troops so they began to put equipment with a specialist. I got my assignment.

We were paid per diem, lots of Piasters (local money) not convertible to dollars, so we had to spend it.

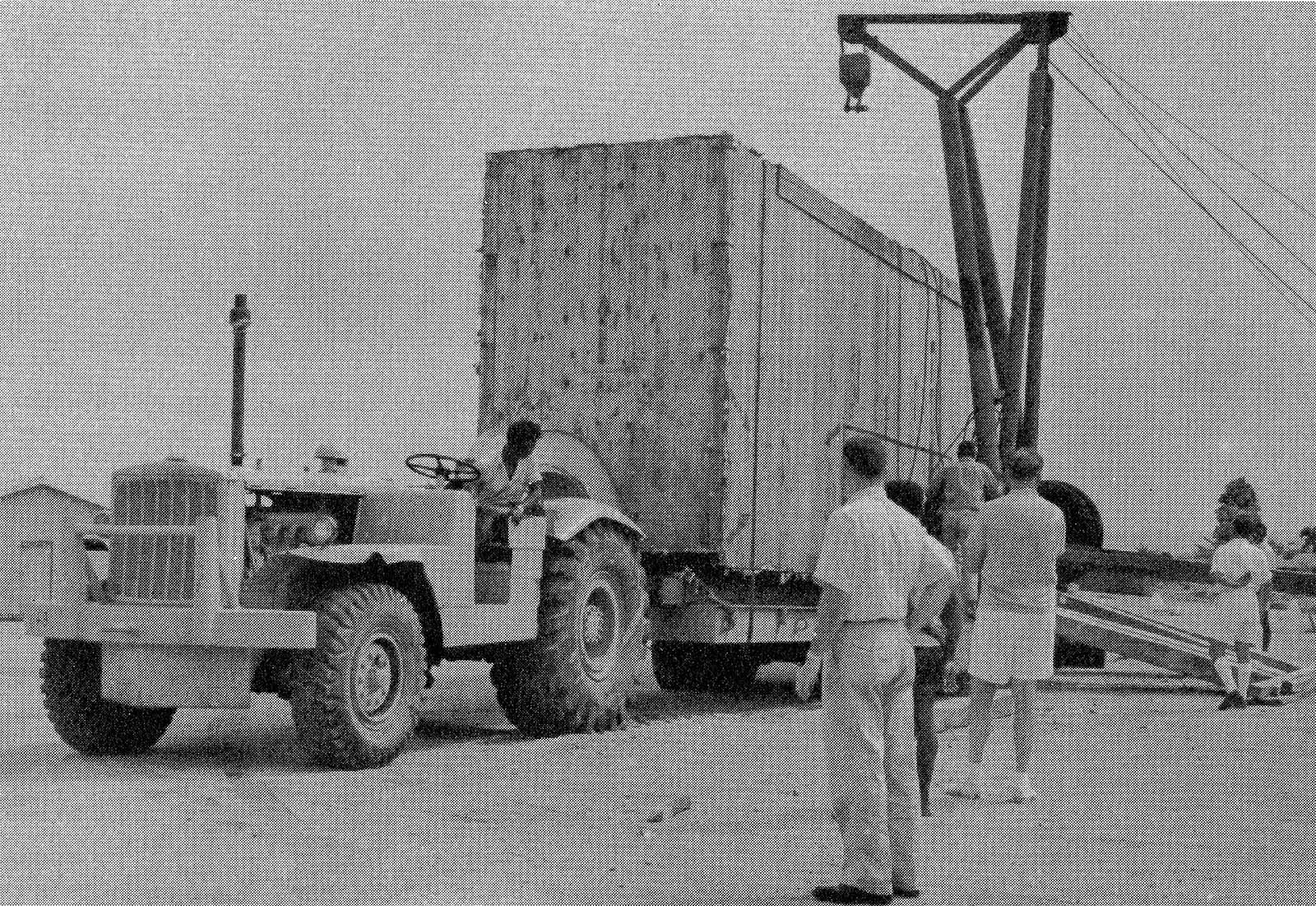

Saigon was booming. It was a beautiful European/Asian city, good food. We waited around there about three weeks or so for the aircraft to arrive. I think it was four of them that arrived in big crates by boat. This was 1953, so they had to have been built in South Avenue in Bridgeport. They were painted silver and black like the Air Force with a big red cross on them. They all had the R1300, 800 hp. engines installed, they were designated the H-19B

We opened the crates, got them ready, did the pre-flight on them, began to familiarize the French mechanics in Saigon with the aircraft, and Captain Good began to train the pilots. The commanding officer of that helicopter unit was the first French certified helicopter pilot, Commandant Santini. He came from Corsica and he didn’t understand any English. He did understand Italian. The only way he was able to communicate was through me, in my Americanized Italian dialect. He communicated with me, and asked me to communicate to Captain Good.

We began the training program and at that time, that so-called squadron was using the Hiller H-23, which was grossly underpowered, and the Westland WS-51 Wessex. Those were the primary rescue helicopters, and far from satisfactory.

Art: You’re just working on the Sikorsky helicopters?

Dan: Just working on the Sikorsky helicopters. We’re there to introduce the H-19B. As we began to get more competent in the training, they decided we’re going to dispatch two H-19Bs to Hanoi. I’m not sure at this time whether I volunteered or whatever, but I wound up as part of the crew. I think I may have volunteered because Commandant Santini was going to pilot one aircraft and Captain Good was going to pilot the other aircraft.

Art: So they needed a translator.

Dan: I flew as the copilot with Santini and I would talk to Good, who could talk to the French pilot. We get the aircraft ready. We took two this time and then went back and picked up a couple more. Took off from Saigon and flew north. We refueled on the way at different locations. We landed and overnighted at a base called Tourane, which today everybody knows as Da Nang. Tourane was the big French Air Force base in Central French Indochina Vietnam.

We slept through the night, got the aircraft ready, took off and we landed at a place called Vinh. Vinh was a very prominent place during the U.S. Vietnam conflict. Carrier aircraft would be flying over on the way to different locations. We landed at Vinh and we refueled. Now we’re refueling from 55-gallon drums with a hand pump. We have a big funnel and a chamois. We’re running the gas through the chamois to filter out any debris coming from the barrel.

We do the refueling, I put the cap back on, I get in the copilot seat and crank it up and the aircraft wouldn’t start. It wouldn’t start. The pilot just kept cranking and cranking, it just wouldn’t start. To this day, I still think about it, why did I do what I did? I got out of the aircraft, I opened up the clamshell doors, I took the covers off the magnetos. I went in the cabin and got the fire extinguisher, and shot the fire extinguisher into the magneto breakers. We tried again and the engine started. I get in the copilot seat and we headed to Hanoi.

I didn’t even cover the magnetos. I closed the doors, I said, “Get in and let’s go.” I guess I was thinking these were aircraft that were heavily preserved. Could it have been that there was oil and grease for preservation that had melted? I don’t know but whatever it was, it worked and we took off. The next thing we know, we landed at the main French air base in Hanoi.

I guess it was that period when I began to say, “I like this. I like helicopters. I really want to be a tech rep,” because I was familiar with tech reps from San Marcos.

I said, “I want to be a tech rep,” and that’s what I did.

Art: Tell me, what were they using the aircraft for, was it rescue?

Dan: It was going to be medical evacuation. At that time, Dien Bien Phu was heating up. That base, you have never seen so many DC-3s taking off for paratroop drops. Because they couldn’t get into Dien Bien Phu, they were doing it all by airdrop. Then later on China Air Transport came in with their C-118s, and they were dropping the heavier equipment and loads,

Remember the French had bottled themselves into this valley. There’s a book called The Last Valley and this valley had over 10,000 troops in what was to be the ending of French domination in the North.

The Viet Minh, at that time, didn’t think they could take that base. Although communists moved heavy artillery up the perimeter of the walls of the valley so that when aircraft were coming in to do drops, they were almost shooting parallel into the aircraft. They had some really horrendous accidents there. Eventually in ‘54, it collapsed, the Viet Minh captured 10,000 French troops and they walked them to Haiphong to send them back to France.

One of the drawbacks on the H-19B, that particular model with the Curtiss-Wright engine, was the impeller was gear-driven. Sometimes when an aircraft backfired, it would shear the gear so then when you go to lift up your collective you can’t get any manifold pressure. We used to have to remove the carburetor, put your arm down the throat, and if you spin the impeller, you knew it was sheared. We had two failures like that. Fortunately, we had two spare engines that had come in that package so we were able to get the aircraft operating. It was also good for training the mechanics.

We operated that way. The aircraft would go, sometimes you’d see some wounded. You’d see people with spikes through their feet because that’s the way they had the rice paddies, and they’d had these spikes or they were crawling in together. It was really terrible. There was a lot of activity but they were great people.

As I think of it now, at that time it wasn’t too bad. I lived in town in a warrant officer quarter, I came in by Jeep every day. We went to the cafeteria for lunch, we had our half a liter of wine, and if we wanted more wine, we could buy some more wine. Then we went for siesta for a couple of hours and then we got up and resumed our activities.

Art: What kind of issues were coming up with the aircraft, reliability, and things like that?

Dan: Mainly the engine – and leaky clutches, the hydro-mechanical clutch. The rotor head was no problem. I had only one time I had to go into the field, one of the pilots was new and he was operating somewhere between Dien Bien Phu and Hanoi and he went “down”. He said he had heavy vibrations so they flew me out in the Siebel high-wing single-engine aircraft. I went out and looked it over, I checked the hydraulic systems and I looked at the rotor head. I didn’t find anything. It looked like he got into blade stall. I was still learning on the machine – but that was the conclusion I came up with.

Art: The whole industry we’re still learning.

Dan: I think it was blade stall. After I did some ground checking on the hydraulics and saw the servo operation, didn’t see anything obvious so I say, “Go ahead and just take it up and bring it back to the base.” I flew in the copilot’s seat for the return to Hanoi. That’s the first time I really had to go into that kind of an environment.

We’re in Hanoi and every day at the end of the day, I go back to my hotel room downtown and I go out and eat. I remember Christmas Eve in 1953. The American Councilor had invited me to join him because there weren’t very many of us there. We were on a rooftop garden in a hotel having dinner outside and you could see flares going on in the distance. The French Legionnaires are raising hell, throwing champagne bottles, having a hell of a good time and I said, “This isn’t too bad.”

(laughter]

Anyway, it all came to an end in January of ‘54. The country fell in May of ‘54. It was divided North and South. I went back to Saigon. The French gave us a trip back to America via Paris with four or five days in Paris in recognition for what we did. I went back to New York and then eventually back to San Marcos, Texas because I was TDY. Then I was promoted to a staff sergeant and I continued to work.

That was the period when people were beginning to get out of the service because Korea was about over with. Unfortunately, my father had a heart attack, he was only 47 years old. It was getting tougher for him to support my mother, brother, and sister, so I received a hardship honorable discharge.

In the meantime, at San Marcos there was a Sikorsky Tech. Rep. that some of you may remember, Stu Hill. Stu Hill, has since passed away – was one of the initial field helicopter tech. reps. There was a fellow by the name of John Holland and a fellow by the name of Red Braun, they were all reps that came through there because that was a key helicopter training area.

I got letters of recommendation from Red Braun and from Stu Hill. I was discharged in July of ’54 on a hardship discharge knowing I’m going to come right up here to Sikorsky and I’m going to become a tech rep. Well, I did. I came here in July, or maybe first of August, I came up to Sikorsky and I was interviewed by a fellow by the name of John Hamlet. He was the field service supervisor, and he goes back to the Vought-Sikorsky days, John, a nice guy, a very talented guy.

He actually relocated to Texas with Vought and then decided to come back and they rehired him here. He interviewed me, he was very happy with it, but he said, “You’re really too young to be a tech rep.” He said, “But I’ve talked to personnel, they would be happy to hire you as a flight line mechanic.”

Art: You had to have a certain maturity and seniority to ensure respect from operators to be a tech. rep. and you were just too young, is that it?

Dan: That’s what he said, my age was too young. I had four years of good experience on the H-19, as much experience as anybody had at that time.

Now, I went ahead and said, “No, I don’t want it.” I turned my back knowing full well I wanted to stay with Sikorsky, I want to be a tech rep. Why did I turn around and walk away from that? I don’t know. I go back to New Rochelle and I’m sitting there and I’m saying– I had visited Doman Aircraft to see if I could get a job and so forth and I’m saying, “Do I go back to Sikorsky or what? What am I going to do?” Because I really don’t know why I did it, I don’t know.

The next thing you know, my mother picks up the phone and says, “There’s somebody calling you from Louisiana.”

I picked up the phone, said “Hello.” It’s the secretary of Frank Lee, who was the vice president of operations for Petroleum Helicopters. She puts Frank Lee on and Frank introduces himself and says, “Would you like to come to work for us.” I say, “What do you want me to do?” He says, “We’re buying S-55s and we need people with experience and we’re willing to pay you $500 a month.” I say, “I’ll take it.”

Art: [laughs] Good money!

Dan: Yes. I said, “I’ll take it.” It’s not a tech rep. I’m back to doing what they offered me at Sikorsky. It’s in Louisiana, it’s away, I get in my car and I go. I walk in the office and I meet this young lady, the very lady that originally called me. By the way, she was a secretary of Frank Lee, I later married her.

Art: There you go.

[laughter]

Dan: I accepted the job, they introduced me, I got my uniform, I immediately went to Grand Isle, Louisiana where we began to take oil workers from there out to the oil rigs. Now we’re not talking hundreds of miles, we’re talking 25, 30 miles.

Not these big rigs that are planted in deep water, these were rigs in shallow water with a barge attached to it, and you’re landing on a platform on the barge, and we’re operating from that. We’re transporting ESSO people out to work. ESSO contracted Petroleum Services for their rigs. We’re getting involved there and all of a sudden, one night about seven o’clock the fog came in, and Grand Isle is truly an island. In the middle of it was a burn-off flare. The crew couldn’t see the landing place but they could see the reflection of the flare. They thought it was the island and they landed into shallow water. Four people died. They drowned. They couldn’t get out in the dark. Of course, at that time we didn’t have proper radio communications. Immediately the guy that ran ESSO fired Petroleum. They hired a company called AF Helicopter, ESSO bought their own S-55s and contracted AF to support and operate the aircraft.

In the meantime Frank Lee of Petroleum is sitting there with six S-55s and no work. We’re getting to the point of having to stop work and maybe take some cuts in pay and so on and so forth.

Art: While he figures out how to get some work.

Dan: Yes. All of a sudden, Petroleum gets a contract. We begin to do work for City Service, for Continental Oil, for Shell and for other companies. We’re beginning to find our way–

In the meantime, after that accident, we had to put rubber floats on the aircraft so they had buoyancy. Then I began to get involved in the transmission shop at the main plant in Lafayette, the home office. I began to get involved in the overhaul, the conversion of the aircraft from land based to floats and so forth.

Art: They did their own transmission overhaul?

Dan: We did everything, yes. We did everything there. Only the engines were sent out and I got involved with that. It was very interesting because I have a lot of respect to this day for companies like Petroleum. They were not dependent upon subsidiaries. They had to have contracts. They bought aircraft when they had contracts.

Art: How big was the maintenance crew at that point?

Dan: Oh, well they were the largest helicopter operator at that time. They had a lot of “Bells”. They probably had a 100 “Bells” and “Hillers” operating all over.

Art: It’s a large crew.

Dan: It’s a large crew, yes and they’re very talented people. In the meantime, I’m getting my A&E license. I got my A&E license there. A fellow by the name of Tisdale, who is the head of maintenance, was also the FAA inspector. As long as I’d tested well on the “writtens” and he knew what I was doing in the shop. It was a matter of when the time comes, I got my A&E and stayed about two years.

I still wanted to be a tech. rep. and I’ve got all this experience. I came back to Connecticut in August or September of 1956 to visit my mother. My father had passed away right after I got married down there. I came to Sikorsky in South Avenue again. I meet with Hamlet, he remembers me. I says, “John, I got two more years of experience, I’m two years older, I got A&E license, I want to be a tech rep.”

He says, “I know what you’re going to do. I got a job for you right now. I’ll hire you right now.” I said, “Well, no, I can’t. I’ve got to go back.” He says, “But you know I can’t hire you. Because you work for a customer and we won’t hire people from our customers.” I said, “If you tell me you’re going to hire me and you got a job, I’ll go back to Louisiana and I’ll talk with Frank Lee and Bob Suggs and I’m sure that they will give you permission to hire me.”

I went back, I talked to them and they assured me, anytime I want to come back, you’re welcome to come back. I understand you want to change the course. I’ll call Sikorsky and tell them, so they did. Next thing I know, Hamlet called me and in September or October of ’56, I left them, came up here and hired on. I had all the S-55 experience so I didn’t need very much of that training.

They sent me to S-58 school. In January, I’m dispatched to Papua, New Guinea, I’m a tech rep.

A subsidiary of Armstrong Flint, called Worldwide Helicopter Services, took over the operation in Papua, New Guinea. They created this company and it’s run by all Australians. There was a well-respected Chinese-Australian who was the head of operations, named Frank Minjoy. A terrific pilot, well-known by Jimmy Viner and a few of the other people. He was a pilot and then there was a Frank Tar who was the head of maintenance. We waited for the aircraft to arrive in Port Morsby, Papua, New Guinea. They arrived and we uncrated them and began assembly. The company that contracted the services was called Australasian Petroleum. It was Standard Oil, British Petroleum and Australian Oil together. Their charter was to go into interior New Guinea and find the most economical way to explore for oil, because it was too expensive to dig roads and keep roads open. They hired Worldwide Helicopter. They contracted three helicopters that Worldwide owned so we put them together and they went to an operational base in the interior of New Guinea,

Art: How many hours a day were the aircraft flying?

Dan: They would generally take off at six, seven o’clock or daybreak, depending on the urgency to get the crew there or bring a crew back. They’d go pretty much in daylight and be ready anytime to move supplies or personnel throughout the daylight period.

Art: But they’re flying all–

Dan: Not continuously. They’d be available, but they would take cement packs and so forth, everything that was required to support the drill rig operators.

Art: The aircraft were pretty reliable

Dan: Yes. It was funny. The first time the natives made a hook up, the big chief of the tribe got a shock because he touched the hook. Oh man, they ran in all directions. Because he ran, they ran. We couldn’t get him back. Finally, we got him to use the stick to touch the hook and then make the hookup and then he’d go like that. He would get closer and the other guys would get closer. We’re talking about primitive people – one guy was obviously the oldest. Lord knows how old he was. They talked Pidgin English, real heavy Pidgin English.

I asked the old guy, I said, “How old-?” I don’t even know if he knew how old he was, but he said, “I remember when the Germans were here.” Germans occupied islands at that time, before World War I. So he was old enough to remember the German occupation at that time. They were funny.

By the time in June or so I was ready to leave, they were on their own. They went on further to explore other areas and they lost one aircraft in an accident. I don’t know whether it was engine power or what, but he landed in a riverbed and it was destroyed. Just for your information, at that time, that was the year that Rockefeller’s son was lost and believed to be taken by cannibals in the interior of New Guinea. On the Kikori River there. It’s very interesting.

I went back to Australia and got in a Stratocruiser and cruised home. When I got home, originally, they were going to assign me to Chile and at the last minute, they made a change and they said, “We want you to go to India. We’re selling another two S-55s with the droop tail. We want you to go to India, receive those aircraft, get them ready for flight, then we’ll send a pilot over and he’ll fly them to the operating base. Then we want you to go to Bangalore, to Hindustan Aircraft Company and assist them and license them for overhaul of the S-55 helicopter.”

Art: Fun travel all over the world.

Dan: My wife, who’s from Louisiana had a daughter and of course, her parents thought she was crazy going to India like that and she was not too keen on doing it, but that’s the way the career is as a rep, so she agreed. I went ahead, went to New Delhi where I got the authorization to work in India and the tax arrangements and all of that, and then went to Bombay, where the aircraft were going to be received. My stepdaughter and my wife landed in Bombay and we stayed there. We stayed in a hotel. You’ve probably heard the name, Taj Mahal Hotel. That was the old hotel. It was the new Taj hotel that was attacked by the Muslims.

It was a typical English four-sided, open to the sky and it was during that time that Roberto Rossellini was having an affair with an Indian actress, while he was married to Ingrid Bergman. We all know the rest of that story there. Anyway, as you travel, you get to see some dignitaries. [laughs]

The aircraft arrived and I got them ready and I requested a pilot, and it was Byron Graham. Byron was only with the company a short time. He arrives and he test flies the aircraft and declares them ready.

He and the Indian Air Force pilots in the other aircraft take off and they head for a place called Kanpur, which is not far from the Taj Mahal. It was the Air Force operating base. My wife and I and my daughter fly down to Bangalore, a very nice place in those days. It was an elevated area, the climate was good. This aircraft factory was called Hindustan Aircraft Company and they were the major employers at that time. Today, Bangalore is the Silicon Valley of India and that’s their space center.

The factory manager was the only Caucasian. His name was Zampolino, he came from New Jersey. Zampolino and Libertino, they figured out, there’s a connection there. That connection helped me with the training program.

When things weren’t going well, I go to the foreman and I say, “Maybe I’ll talk to “Zamp” and see if I can step this up, do something like that.” They say, “Zamp?” I say, “Yes, Mr. Zampolino.” “Oh, no, Mr. Libertino. Let me look into it, see what I could do.” It always worked.

[laughter]

Dan: Anyway, we were able to get one aircraft flyable out of the two damaged shells. I was still qualified to crank up the engine, engage the rotor and do the mag checks. We did all of that, then we brought the military pilot down, he flew the aircraft and they were all happy and I transferred to the U.S. Army Forces in Hanau then West Germany.

From there, we were assigned to Germany. Flew to Germany, and we arrived in December of ‘57. I was assigned to what was called the 54th Aviation Battalion. They operated three squadrons of H-34s. Each squadron had 25 aircraft in them. Plus, there was another 50 aircraft spread out from the Eastern border to the western border, across the northern half. Hanau is a city about 40 miles north of Frankfurt and they had what they call a fliegerhorst (airport) or an airbase that used to be German that the U.S. Army had taken over.

That’s where the primary operations were, but I had to cover all of the other satellite facilities and then there was another tech rep in the southern half. In those days, Sikorsky built aircraft dominated that arena. H-19s and H-34s were all the way north and west. It was very interesting with a lot of good experience on it and I enjoyed it very much. Then the U.S. Army was going to phase in the S-56 (H-37) into that battalion.

Sikorsky decided to bring me back to the States and put another rep in country that had experienced on the S-56 as well as the other two. That’s fine. I came back and really, this is now my first assignment as a tech rep in the U.S. Again, I was scheduled to go to South America and at the last minute they changed and said go to San Diego. Now, San Diego, at that time, the Navy was operating from a base called NAS Ream Field. It had four anti-submarine warfare squadrons and one training squadron. They operated the H-34, or the S-58. It was then called either the HSS-1 or the -1N. The -1N was the fully automatic approach aircraft and so on. The turbine powered SH-3s (S-61) later replaced the HSS-1N aircraft.

When I got there, I was scheduled to go on an aircraft carrier, and I was a little bit disappointed because my wife was then pregnant. Anyways, it turned out one of the reps volunteered to go on the carrier so I “was off the hook”. I went up to North Island. Now, North Island was really the hub of Pacific Naval aviation. That was where the Commander of Naval Air Forces Pacific (CNAP) was based.

It’s where his “flag” hung. He was responsible for all of the Navy aircraft in the Western United States and the Pacific – fixed wing and helicopters. It was structured so you had a class desk for each model aircraft. One covered Sikorsky, one Kaman, one covered McDonald, one covered Douglas, etc. Each of the tech reps for those companies would be working with that individual, which meant every morning at seven o’clock we were there and we would see all the message traffic coming in from the Western United States and the Pacific on our helicopters.

Then we screen through and make decisions. What are we going to do? What do we want to tell them? That type of thing. That happened religiously. Seven o’clock in the morning and again at four o’clock in the afternoon, we’d go there. We go through all of that and do that again. Remember, Vietnam now was beginning to pick up. In ’60, ’62 the first squadrons were over there. In fact, coincidentally, my father-in-law was a retired Marine Corps Colonel, and he was an aviator in World War II, Korea and in Vietnam. He took the first H-34 units over to Thailand and later turned the unit over to Air America.

The North Island Depot overhauled all Sikorsky products, including the main rotor blades and all the dynamic components. Plus, they did McDonnell and other aircraft and engines, but from a helicopter standpoint, they were totally in control. We were seeing more of the source history of the aircraft there than Sikorsky. After I got through with the headquarters, I would go and begin to “walk the shops”, the blade shop, and the transmission shop, etc.

Of course, during the period of time from 1959 until I left in May of ’71, we were involved in the H-19 (S-55), H-34 (S-58), the introduction of the SH-3 and the introduction of the CH-53.

Because of all that activity and seeing the history, I would get to see a lot of people from Sikorsky. I had never worked at the plant so I didn’t know anybody other than whoever my reports were forwarded to for additional dialogue.

On the H-34 I was beginning to see problems with the hydro-mechanical clutch leaks. Al Koup came over from Sikorsky to North Island with many other engineers. The aircraft is throwing oil all over the place. We had to do something, and he’d come in. I don’t know how many trips he made. Les Burroughs used to come on the H-34 for the drive shift. Somebody else would come for structural problems. We would see all of these guys were coming through there, along with the program managers like Bob Barlow and Bob Campbell and the engineering types. I remember when the H-53 was introduced: it was introduced up at MCAF Santa Ana. They were doing some high altitude work and they came in and did a flair and landed, and they barreled into the ground so hard that they buckled the tail cone.

They insisted that was a weak spot. You could see the impact into the ground. Harry Jensen came out, Bill Whiteside came out, and other structures people.

There was an Engineer by the name of Hank Nelson at O&R who worked for Consolidated Aviation in Buffalo, New York. He had a tendency to solve all problems by putting a plate steel on it to beef it up. That didn’t go over too well with Harry Jensen so there was a very heated discussion. They were both about the same age at the time and very talented.

Anyway, the end result was Larry Petrocelli took a team out to get the aircraft off of the hillside. They brought a whole completed transition section from Stratford, mounted it and got the aircraft back. In the meantime, a decision was made to put a “beef up” at that area, the transition area coming up out to the boom and Bill Whiteside played a key role in that. That was the introduction to the H-53.

If you had rotorhead problems, it was a specialist named Lou Vacca or Ed Robitaille. If it was a transmission problem it was Les Burroughs and Paul Fitzgerald. If it was blades, it was Tom Dixon. We had a very big blade shop and we did a lot of repairs.

The O&R engineers were not the typical civil servants. They had come from private industry. They were very talented people and good to work with. I was young then by comparison, but got along with them pretty well. I was reporting everything back to Stratford.

Let me just start from the H-3 days. One thing we worked on was oil leakage with the rotor head on the H-3D and the free-wheel unit on the main transmissions. Structurally we detected station 290 cracking.

Those were some of the things being detected and reported back to the factory.

North Island was pushing, they wanted to overhaul an H-53 aircraft so that they were ready to get the first ones that come in. We got the first prototype aircraft that Sikorsky used, the 53 was sent to North Island. Then they created what we call ECN kits, little kits to bring the aircraft up to a standard. It was massive undertaking, I mean, the kits you can imagine the numbers of– This was a little bit different for them because they normally had a finished aircraft with drawings you can follow.

Now we’re upgrading it to the production standard that developed publications. All of this history that meant that I was gaining tremendous experience and getting in contact with people all throughout the factory, I was talking to engineers that develop airframe changes, people who write publications, people that write the changes, etc. That was my connection with the company. Some of them I never met, if they didn’t come out to North Island, I just talked to them.

Art: I’ve always been impressed. When you think about just the growth of the size of the helicopter from the S-51, S-55, to the S-58, S-61, to the S-65. I mean, that must’ve been—every time you saw a H-53 coming. [laughs]

Dan: Well, but think about it. Think of the R-4 in 1943, probably about 2,000 pound gross weight, and then think of 1953, the H-56 at 30,000 pound gross weight. A hell of a jump, of course, the engines.

Later at North Island, as a result of an incident in the mid-west that involved an S-58 helicopter, the blade shop was contracted to retrofit main rotor blades with the BIM (Blade Inspection Method) system as we know it today. Of course there were lots of aircraft out there that required the BIM modification. The kits were created and then we did the prototypes there at North Island O&R Depot. We did everything that Sikorsky could do in Connecticut..

O&R North Island Depot had a whirl tower just like Sikorsky. We did everything that Sikorsky could do there. The head of that was a fellow by the name of Don Wilson. He used to work for Ryan Aircraft. Very fastidious guy, he may have been 65 or 70 at the time, very dedicated. When it came to blades, this was the guy you dealt with. We had a lot of blade repair activity, so I was in contact with Tom Dixon who visited very often at that time.

We had a particular problem and it may have been at the time we were doing the BIM blades and Don wanted to go off in one direction, and Sikorsky had recommended something else and it was taking him forever to make a decision. Now, Don was the designer of the Spirit of St. Louis.

Art: Really?

Dan: If you see a picture of the original Spirit of St. Louis at the Ryan factory with the mechanics and the engineers, Don is at one end of the line and Claude Ryan is on the other end.

Art: [laughs]

Dan: I haven’t got enough confidence with him, even though I respect the age difference, but we know each other and I do a lot for him, and he does a lot for me. I got to the point, I said, “Don, how in the hell did you ever finish the design on the Spirit of St. Louis? We can’t get this simple thing going”. He says, “Let me tell you, son, that aircraft was not finished when he took off”.

That experience got me to the next step. In the mid-70’s the Germans were making a decision on a helicopter buy. They were looking at the H-47 and the H-53. Whatever they did at the operating base, they would come to North Island as a team and look at the H-53 gearboxes, the blades, the condition of the aircraft, and get a feel for what’s going on. When they’re out there, I’m the main interface with them.

Now, I don’t mind telling you, I knew what was going on with that aircraft because I could see it every day and I’m reporting it back to Stratford and I’m having discussions on it. I knew what was happening, I felt good about it. I was confident and I’ve been there for 10 years, and so I knew I was– Well, that caught their attention. Finally, the Germans are coming in. Now, all of a sudden I’m getting calls from John D’Angelo who heads up the field support department. He says, “Danny, the Germans wants you in Germany.” I was like, I’d already been there once, I’d like to go back.

I left for Germany in May of ’71. The German co-production program had started already in 1970.

Art: The aircraft is the 53?

Dan: Yes, it’s called the CH-53G. It’s a Marine Corps aircraft with automatic blade fold and has a rescue hoist, and some little things like that. It’s a co-production program. Germany has the license to co-produce it, and they have given the license to a group headed by VFW-Fokker (Vereinigte Flugtechnische Werke). It meant United Aircraft Works. They were the program heads who then subcontracted manufacturers like Dornier, Siebel, Fokker. They all took pieces of the airframe, Siebel manufactured the blades. That was all structured in a team of about 15 people, specialists in manufacturing, quality programs, whatever. Well, the original team went in place in 1970. I followed along in 1971. My job was the manager of logistics support.

It was to transition into what the service department at Sikorsky does for the U.S. Marine Corps, they are going to do for the Germans. It was a very political situation too, and now I’m there at the head of it. I have a counterpart in Germany, we sit side by side and we begin. They translate the manuals into German. The army gave us a list of 25 companies who are going to be the overhaul depot for these components.

I’m working with the designated companies preparing the overhaul manuals. We began to have trouble in manufacturing with leaky rotor heads. The other one was a transmission problem with the planetary gears. We get an early start on repair of rotor heads and the transmission by doing repairs under warrantee using Sikorsky paperwork.

When I left in October of 1975, German industry was fully capable of supporting that aircraft and they have demonstrated it ever since.

The program is still on-going, I think they’re currently operating 80 aircraft. It was a very successful program. I enjoyed every bit of it. Terrific experience. It was probably the last big program in Europe that we had.

Then I’m asked to come back to the States.

This is 1975, and I’m going to be reassigned to the Iranian Program. Before I can go to Iran, I’ve got to come here, put together a team of 25 people and I’m going to supervise the team in Norfolk, Virginia, maintaining two U.S. military RH-53Ds for minesweeping. While the Navy is training Iranians, we’re maintaining the aircraft.

Art: The Shah is still in charge?

Dan: Yes, the Shah is still in charge, we’re delivering seven minesweeping aircraft from here, they’re training the people. I put the team together. We had two shifts. During the one-year period, we flew those two aircraft 1,200 hours and towed 600 hours. That was more than the U.S. Navy squadron had done since their inception.

Of course, the Navy was helping us, giving us parts to keep it going, and we had the dedicated people to do it. As a result, they were training Iranians as well as U.S.N. operational personnel in control. This goes on and we’re doing quite well. Then we get into ’76. All of a sudden, Al Poole calls me and says, “You’re not going to go to Iran anymore. We want you to return to Sikorsky to become manager of logistic business. We want you to be responsible to solicit aftermarket business.”

I came back and began the position and then things started to happen – they were closing the helicopter depot in North Island and moving it to Pensacola. They needed a transition period so I began to market our capability to take over the H-3 and H-53 dynamic component overhaul. That put me working directly with Sikorsky O&R on South Avenue in Bridgeport. We successfully get that contract and begin to take it over. What was supposed to be a year went on for five years. This was followed by a demonstration in Switzerland. The Black Hawk aircraft was going to compete against the Puma. Ken Horsey asked me if I would put the team together to support the Black Hawk in that position as logistic manager.

I did that. We went to Switzerland and did the competition, a one-month intensive competition. That was the time when I first met Gene Buckley. Gene was the program manager of Black Hawk and he and his wife had come over. My wife was also over there for a while. A very intense program, we were up at five o’clock in the morning, we got our briefings, we went to our respective hangars, we had our own Swiss people looking over our shoulder, Puma had their own. They gave us a mission, we pulled the aircraft out, they watched everything we did to get ready for it and then perform the mission.

One mission was to “cold soak” the aircraft over night at 12,000 feet and observe the restart the next morning. In the end, we won the contract technically but then lost it politically. But it was a fun time, hard work.

There used to be a restaurant called “da Peppino” in Lucerne, Switzerland and they got to know us and would set up the table for us and fix our meals when we ordered. You’re putting a lot of hours in, up early but it was just fun, it was a terrific program.

I came back. I don’t particularly like doing marketing. I want more of a hands-on business, and I’m getting deeper, deeper involved in the overhaul and repair. By that time, I think Kenny Clark had just become manager. He replaced Charlie Gullotta. I finally went to Al Poole and said “Al, I have some ideas for O&R. I want to take over the position of superintendent of services for O&R. The Black Hawk is going to be introduced and I’ve got ideas. I want to put program managers in and I want this guy, this guy, this guy, and this guy out of service over there to take over program positions.” I went over there in ’81. We were operating out of South Avenue and in the hangar at the airport. We were also doing presidential and crane overhauls. I had about 160 people. We did the service, we took the orders, we processed the orders, we interface with the customers, prepared the material and so forth. It was really good, I was very happy with it.

I think at that time in one year we did about $65 million business. I mean today it’s peanuts but at that time it was substantial.

Gene Buckley was not the president yet but he’s getting close to going into that office. A requirement came up to take a Black Hawk on demonstration in Germany. Now I’m in the position as superintendent, so they come to me again. Al Poole says “I’ll let you go, but you’ve got to ask Buckley.” I go to Gene and he says, “Do you want to work here or do you want to go in the field?” I said, “I didn’t ask to work here, they asked me to do it.” He finally said, “You can go but this is the last time, you either plant your feet here or it’s over.” I go to the Hanover Air Show, we tour Germany from south to north and again it was very successful. These were the days when they were trying to find a replacement for the Bell UH-1.

Next I came back to Stratford and got involved. But I finally say, “I don’t like the factory.”

Jim Satterwhite was about to deliver the first SH-60B to IBM in Owego, New York. The Navy said they would pay for a team of 20 to 25 people to be responsible for clearing interface problems between IBM and Sikorsky, and maintaining the flight operations of the aircraft and interfacing with the NAVPRO. This would be the Sikorsky team. It was very sensitive because Sikorsky was not happy that IBM was the program manager but we were the builder of the aircraft.

I go to Al Poole. He says, “Oh damn. I’m not making this decision. You’ve got to go to Buckley.” Buckley is now the president, I asked why I had to go to Buckley. After all I work for him. But I went to Buckley, and he said: “You want to go to Siberia? What do you want to do in Owego, New York? It’s so cold there.” I responded; “Look, I’ve been here now 20 some years. I spend most of my time on the road. I’m more comfortable out there.” He says, “Go.”

[laughter]

Dan: I put the team together. It was very good, we made the transition. Of course, there were a lot of politics – IBM owned the facility.

We had problems with IBM because they used to wear white collar and tie. The hangar was pristine, not that we were overly messy, but we’re mechanics; we’ve got tool boxes and have to somehow maintain the aircraft at Owego

Finally, we built up a rapport and they allow us to do what we do best.

The top tower operator and the aviation people knew what our expertise was and began developing a strong rapport with the NAVPRO office. Then the first aircraft arrived and we go through it. They have a big ceremony on delivery. Bill Paul was now the president; Jim Satterwhite came up. Gene and others came up. We all dressed in uniforms.

We did a first-class job, and got a good response from the IBM people. They were happy that it was going well because they were concerned that if things didn’t go well it fell back on them. We were always one step ahead if a problem showed up. As soon as the aircraft came in with a problem, we knew where to look. If it was a familiar problem, we’d find it right away and deal with it. That went on.

About two years later Sikorsky won the Fort Rucker Maintenance operation. This was the first maintenance contract for Sikorsky Support Services Incorporated (SSSI). They asked me to go down and be part of the team to transition as the old guys move out and the new team came in. I began to get involved in SSSI.

At one point we were going to convert the SH-3As to a new configuration and they wanted to do it in Troy, Alabama instead of in Connecticut. But Troy was having trouble getting certified for quality. They asked me to go down there, and I spent a lot of time in the certification process, getting familiar with the people and so forth. We did get Troy certified but then the military would not pay for the differential to move it down there. The aircraft remained at Stratford.

I was beginning to think that it wouldn’t be bad to retire in Connecticut. I don’t mind the winters. It’s quite comfortable and the work is interesting. And in late 1985 they asked me come back to Connecticut. I was to continue to work with SSSI and do some other work inside. I said, “Okay.”

We sold our house, and moved back to Stratford. I bought a condominium in Oronoque Village where we live now and came back to the plant.

The next thing I knew it was January. We had won the contract to refuel all the helicopters at Fort Rucker in addition to the maintenance contract. This involved probably 20 or 25 outlying fields where the helicopters were used. They would go there and do the touch-and-go testing, and we had to refuel them there. The refueling fleet was about 50 refueling/defueling trucks.

Although SSSI had won the contract they didn’t have a clue where the first refueling truck would come from. They said, “Dan, go down there and lease trucks, hire the people, get them in uniform, be ready for April 1st.” I said, “Are you crazy? I don’t know how the hell to do that.”

Well, I went down there and I looked around. There was a guy that used to refuel at that base and had lost the contract four years prior. They had 5,000-gallon tankers, they had smaller ones, they had de-fuels, they had everything you needed for fueling and they’re laying in that field. I asked what it would take to refurbish them to current standards, painted, readied for April 1st, and maintain the trucks once they’re in service? He gave us a proposal and I gave it to the people here. They okayed it and I signed the purchase order. They started taking the rust off, painting them yellow, putting the big Sikorsky Aircraft Service logo on and buying the uniforms. The trucks were lined up in a row. We looked like the Red Ball Express.

Midnight April 1st, boom, the effort is cranked up and the trucks are rolling out of the yard. Fortunately, the hiring of people was pretty easy because we had been operating the Fort Rucker operation. We had an HR department in that area. Most of it was rehiring of older people. We got them special shoes and all the things they needed. That went pretty smooth and was successful. I watched it operate for a couple of weeks and then came back to Sikorsky.

Then they said they would like to start a technical writing operation in Pensacola. I said, “Well, yes. Okay. I don’t know that much about it, but I know who does it and basically how they do it.” I went down there. I took a guy from the tech pubs department here who wanted to relocate down there. We went out and hired 40 or 50 people. I found the building. I worked with Dick Belden in those days and he approved it. I signed the lease. I was working with Dick Weich, the tech pubs manager. We hired the people and started the operation.

I’m thinking, “Now, I’m going to be relocated there.” They said, “No, we want you back at the plant. We think we want you to get more involved in either marketing or setting up a service organization for Australia.” I said, “Oh, hell, I’d like to stay there (in Pensacola), it’s pretty good.”

Anyway, they went operational. I came back to Connecticut and I started to journey back and forth to Australia. At the time the Australians had just had selected Sikorsky. They were trying to get Hawker de Havilland to become the support organization for the Seahawks and Black Hawks.

Art: Okay.

Dan: They are trying to get them to take the lead and be the service organization point, but it was a torturous affair. First of all, in those days, every time you tried to do something, the government was against you, whether it was the U.S, government or a foreign government, they wanted to keep everything to themselves. It was very difficult to do that. They had depots they wanted to support. That’s all changed now. Now contracting out is the way of life, but in those days, trying to get them to contract out work that they traditionally did in-house, was very difficult to do.

Anyway, I went back and forth several times and it didn’t go well. I backed away and they assigned me as a manager of Sikorsky international derivatives. I had the logistics support for the Black Hawk, Seahawk, and the Japan program. I forget two or three other international programs, but mainly I also had the Australian program.

They had to put a team together and I let it be known that I was ready to go. I said, “What are they going to do? I’m already approaching 60 years old. I’ve got all these years of experience. It can’t get any worse and I know what it’s like to go overseas.” The problems they had were because they had people who didn’t know how to operate overseas. I felt very comfortable with it. Jim Satterwhite was the program manager. He knew what I did up in Owego. We had crossed paths throughout. He was very supportive of it and he said, “All right, I’ll go forward with it.”

I was selected as the Director of Operations for the Royal Australian Navy Seahawk Program in 1989. My initial assignment was to assemble, test, and deliver Lot ll’s eight Seahawks with kits delivered from Stratford. Our Sikorsky team relocated to and worked at Avalon Airfield in Geelong. I was further tasked to oversee an additional Sikorsky Aircraft team to upgrade the eight previously delivered Seahawks to Lot II configuration.

During the final months of the Seahawk Program I was appointed to be the Managing Director of SAAL and relocated to Canberra where I continued my duties and gained responsibility for oversight of Black Hawk Program in Sydney at Hawker de Havilland.

Next I was assigned to Korea. We lived in a hotel in downtown Pusan and I began to go to Korean Air every morning.

It was the most rewarding assignment I’d ever been on. I have never seen more dedicated, hardworking people. When I got there they had just started the manufacturing process and the idea was to build a whole airframe. We would provide the dynamic components and some kits for things that were not practical for them to make. We had a small team that was interfacing with them, much the same as we did in Australia.

Now I began to have problems with Sikorsky. This is a licensee, Korean Air is responsible. But we’ve got people back in Connecticut thinking they still own the aircraft, and they’ve got to do this and they’ve got to do that; what about our reputation? I said: “They’re a licensee, what can we do? We’ve got a bigger problem with you. When we open these kits that you’re sending us, parts are missing. I’ve got to put in a warranty claim and you’ve got to fill it, and you’re not filling them.”

I got there in January 1992, we delivered the first aircraft in December 1992. By that time they were building the entire airframe. They had completed the cockpit, the tail cone, the pylon and completed the first cabin. They were going strong. Produced 133 aircraft. Never missed a schedule. Terrific, terrific program.

Next I was scheduled to go to Turkey. I was to be the Managing Director of UTIO/Sikorsky.

Art: Okay. What year are we into now?

Dan: This was in January of 1993 and we arrived in Turkey. We had a contract to deliver 50 aircraft and manufacturer 50. Originally it was a big co-production contract, but by that time, Turkey was at the peak of the PKK (Kurdish conflict) in eastern Turkey and they needed helicopters right away. They had delivered five by the time I got there and then over the next year we delivered 40 more.

Now, this was a big program and the American Embassy was definitely involved. We had the strong support of the ambassador, the deputy ambassador, the staff, and the commercial people because it was a big program. As soon as I arrived in Turkey the security people called me in for a security briefing. They said, “Dan, you are the highest potential level of risk by the PKK. You have to be careful because you’ve got to have some security, be conscious of security.” We had a driver and he had the ability to check the car and start the car in the morning and stuff like that.

Art: Was your wife with you over there or you were by yourself?

Dan: Yes, she was. The security people came out and they checked the apartment we lived in. They said: “Here’s how you can get out because there was no fire escape and oxygen bottles and all of this.” I began to feel confident; I didn’t feel intimidated. I had a warm feeling for the Turks, which I still have today. I still go on vacations there. We have a lot of friends there.

I decided to start walking to work. He said, “If you do, when you get to the front door of your house, be sure that you don’t see the same person every day, change your course a little bit and do it.” I said; “Okay, well, I will do it.” I began to do that. I’d walk to work and then take another route home, and so forth.”

I made some trips east in ’93 or early ’94. It was the first incursion of Black Hawks across into Iraq. The Turkish forces were chasing the PKK. There’s a picture that was in the newspaper where we were on a mountaintop at about 10,000 feet. The trucks are coming up with the troops, and the troops are all milling around. There are Black Hawks positioned all over the place and some are flying and others taking off. Beautiful picture, the massing of the troops there. I sent it back to Sikorsky and they used it. After that they flew the Black Hawks as necessary, and it was very successful.

All of the sudden one day, it was a weekend, the local English paper came out with a big headline: “Turkish Military Purchases 23 Pumas.” Sikorsky was very upset. The phone was ringing and the teletype machine was operating. Sikorsky was asking what’s going on? I responded that I didn’t know. I said that I just read it in the paper. He said they can’t do that, we’ve got a production contract and this and that. I said, wait, let me talk to the military, no not the military, but the embassy people. They did some nosing around and come back and said, “Look, the Turks are just that way. They’re going to do whatever they want to do, when they want do it. If you raise hell you’re going to jeopardize whatever future potential you have on that contract. Just sit tight and wait.”

Now, can you imagine me telling Buckley, “Sit tight, be calm.” He responded: “Who the hell are you working for? You forget who sends your check.” [laughs] That’s the way it was, and that’s the way he said it.

Art: How did it get resolved?

Dan: It didn’t really. It went into Limbo. We didn’t do anything. The next thing you know it started up again. It took several years and they began to negotiate a follow-on contract for the Seahawk. Then another one, and that’s the way it is. Today, Sikorsky is waiting for a decision that’s been delayed for a year and a half now for another 125 aircraft to be co-produced in Turkey. It’s going on. In the meantime, we have tremendous offset obligations.

The Turkish Airline system, Turkish Aerospace International, is manufacturing the tail cone and pylon for the Black Hawks today. They built the F-16 before and they will be the potential manufacturer if Sikorsky gets involved later. We also, through offsets, set up a factory in Eskisehir, which now does flight safety parts and transmission parts manufacturing. The value of that is you invest in the plant and then if you get a million dollars of export out of that plant they give you a multiple of four, so you get $4 million credit. That’s how you get to weigh it. Another thing we did was built a big hangar at one of the military facilities and set up a depot and get credit for that. That’s going on, it’s a big obligation, and it’s still going on today to try to finish up.

That went on for about three years and I’m approaching 65. I’m tired. I had a tremendous rapport with the Turks. But, I’ll tell you, I never felt like I influenced anything because they’re going to do what they want to do when they do it. The fact that I could pick up the phone at anytime and get a meeting for Jim or for me or for anyone at any time, at most levels, was telling me that they had a respect for us and that was good.

I finally decide that it’s about time to get home and spend a year at home and then retire. I’m beginning to close down and letting Jim know that I want to retire. He asked me to just stay on a little longer. I said, no, I’m really tired. “It’s taken a lot out of me here. We want to get back and get a feel for the states.” By that time I was almost eight years out of the country. There was nothing we disliked about it. Even the Turks, as hard as they were to deal with, still treated me with respect.

In fact, when I was leaving and saying goodbye to some of the people I closely worked with, I remember one guy in particular. He said “Dan, why are you leaving? You know us, you like us, you understand us, why do you want to leave? You’re not American. [laughs] You’re like us, you’re Italian. Your father came from Sicily, You’re here.” I say, “No.” [laughs] It is a good feeling in a way, but you’ve got to face reality. It was time to go.

By 1995 things were going along pretty well in Turkey. We had delivered all the aircraft. We were beginning negotiations for the Seahawk program. The XM loan was still in place. We technically still had the contract, the ability to go into co-production for 50 aircraft. But it drifted to the Seahawk and we began to go with Seahawk negotiations. I think it took another two years before they finally made the decision and bought the first lot of Seahawks.

In October 1995 I was transferred back to the states and assumed the position as manager of international customer support, reporting to Brian Young who was head of the WCS program, and was responsible for foreign customers. Because I had in mind that I was going to retire it was not a very interesting time. It didn’t do what I thought I was going to do. We did settle back in our condominium and prepared for retirement.

Then I began to do other odd jobs. Finally, in February of ’97 I asked to retire. I just walked away. I didn’t want any party. I didn’t want anything. I didn’t even tell Gene. I get home and I’m tired. I took a year and then I’m rested, I’m reading, I’m very relaxed, I’m getting reinvigorated. The time comes when I want to do something again.

Art: You flunked retirement.

Dan: Almost to the day. So I decide – I told my wife that I was going to go in and see Gene. I made an appointment and went in to see Gene and he says, “Oh, thank you, thank you for coming in. You wouldn’t even tell me that you were going to retire. I had to find out from somebody else. You know, I could’ve given you a leave of absence, I could’ve done. . .” I said, “Gene, to be honest with you, I was tired and I didn’t want to tell you no. I appreciated what you were doing. I suspected that you would want to do something else, and I didn’t want to say no to you. That’s the way it worked out.”

Art: He bought that?

Dan: Yes. I said, “Having said that, I’d like to do something.”

[laughter]

So we chatted a while. I began to do some consulting work. Sikorsky Aircraft Australia, or SSSI as they were called, he asked me to go back to Australia and restructure the company with all Australians. Send the Americans back home and restructure it. Then negotiate a Sikorsky support contract with the government, with a program to support Black Hawks and Seahawks services, publications, spare parts and so forth.

I wound up going back and spending six months in Sydney, which was great. I had not lived in Sydney before, so I enjoyed that and got back to see a lot of familiar people. In every place I went, people knew me. Even though it was ’99 and I left Australia in ’93, there were still a lot of people around, so it made it very comfortable for me. It was really good.

Then I did some other consulting work for product support.

Finally, the last job I did was working on the logistic part of the contract for S-92s for Canada. I was on it until the best and final proposal. How I got involved was not through the typical support services track, it was Steve Shirkus. I knew Steve pretty well. He was pricing the program. The logistics part was a big part of the contract. I think it’s a 20-year firm-fixed-price contract for all the support. He wanted someone who understood logistics to look over his shoulder. I did that and really enjoyed it, two or three days a week.

After that was over, I just said stop. I started to get involved with the Archives. I was coming into the archives when I got called away again. I just broke away for a period of time and then came back. I finally made up my mind that I didn’t want to do that anymore. I’d get some calls and they’d say, “Would you come in and work the proposal for us?” I’d say: “You’re talking about not five days a week, you’re probably talking about seven days a week, 16 hours a day. I don’t really want to get involved in all of that.”

I wound up just refusing and getting deeper involved in the Archives until I was asked if I would take over the presidency. I agreed and I’m now in the sixth year [now 18 years, in 2022] as the president of the Archives. I get a big satisfaction over what we’ve done and I like doing it. My biggest problem is that I don’t have enough younger people who show an interest in continuing the program. That’s a big problem.

Anyway, the Archives is great. We’re making a lot of progress. I enjoy answering people’s questions. We give presentations to community organizations. retiree clubs, and new employees of Sikorsky.

A few of us are called upon to give tours of the factory, which is turning out to be very, very active. They can be community groups, boy scouts, family members. A lot of what I do is working with customers, particularly customers from countries that I worked in previously, where I have a connection. Last week, I did some work for the offset people in Turkey. One of the guys I didn’t know, but he knew me because he was young person on the program years before. Now, he’s a leader. He says, “I know you. I know the people that you mentioned, that you worked with, and so forth.” That’s very satisfying.

Occasionally, we’ll do interns from UTC or different places. If I see an Indian, I’ll ask, “Are you Indian? Well, I lived in Bangalore in 1957.” “Oh. I wasn’t even born then.”

One particularly thing stands in my mind. I was giving a tour for interns from UTC and a young lady was Indian. After the tour was over, I talked to her and I told her. She was really elated that someone knew where she came from because she came from Bangalore. I said, “My daughter, who was then about 9 years old, maybe 10, used to go to the Catholic school within walking distance from our cottage on the grounds of the Bangalore Hotel.” She just lit up and said, “Oh my God, that’s the school my grandfather used to take me to all the time.” It’s good to talk about those old things. As long as it’s still fun, I hope that I can continue to do it. Thanks again for the opportunity. I hope that somebody years from now will talk about it and look at it.

Art: It’s fascinating. It’s been a great career.

Dan: Thank you very much.

On 12 October 2023, the Igor I. Sikorsky Historical Archives formally opened its new home at Sacred Heart University (SHU) in Fairfield, Connecticut.

Sikorsky retirement did not stop – or even slowdown Dan’s devotion to the Sikorsky legacy as he has dedicated over 18 years to the I. I. Sikorsky Historical Archives (IISHA), which he continues to this day. Seventy-One years and counting!