Personal Recollections

History in the Making: The First Helicopter Delivery

by Charles Lester Morris

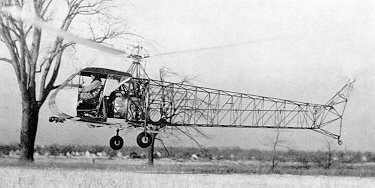

Finally it was settled that I would leave for Dayton on Tuesday, May 13. So on the preceding Sunday we made the last few tests and then turned the ship over to Adolph Plencfisch and his crew for final preparation.

Tuesday was a beautiful warm day, with the temperature close to 80°F and a gentle breeze barely stirring the stately elms that bordered our little field. I sat inside the blunt-nosed cabin, reading the instruments that would tell me when all was ready, arranging maps and parachute harness, watching the rotor flicking overhead in powerful rhythm. Several of my friends drifted out of the crowd and stuck a farewell hand in the open window.

Mr. Sikorsky hovered near, nervously chewing at the corner of his mouth. His keen gray-blue eyes flashed out from under the familiar gray fedora as they searched every detail of the craft to detect any sign of flaw. I knew the capacity of those eyes from experience-that time they had seen from twenty-five feet the strut that was so slightly bent that I had to sight along it at close range to notice it-the time when, without apparently looking at the ship at all, he had commented on a tail-rotor blade whose tip had an eighth of-an-inch nick in it. And I knew on this May morning that his vision would be doubly sharp because he was not wholly convinced of the wisdom of the impending flight-he felt that this “first-of-the-type” should be handled with kid gloves and should be delivered to Dayton by truck, thus eliminating the potential hazards of a cross-country trip in a totally novel type of aircraft that had had less than twenty flying hours since its wheels first left the ground. So I knew those eyes would probe to the marrow any minute indication of things awry.

It is understandable, therefore, that I experienced a calm reassurance when he walked quickly to the ship, thrust out his hand, and said, “Well, Les, today you are making history!”

But I couldn’t tell him what I wanted to: that I was only the ball carrier in a football play that was destined to be a brilliant touchdown. The play had been nurtured and studied in Coach Sikorsky’s mind since 1909. It had profited enormously from similar plays worked out by other coaches throughout the world. The snap of the ball had found a stout engineering and shop team on the line and in the backfield running the interference, taking the knocks, and clearing the way, so that now the lone ball carrier might trot across the goal line standing up!

The engine roared its crescendo as I pulled upward on the pitch lever. The ship lifted vertically to ten or fifteen feet; then I eased forward on the stick and started across the field. Sweeping in a gentle circle, I swooped low over the clump of upturned faces and waving hands-on over the factory and into an easy climb to 1,500 feet.

A car with a large yellow dot painted on the roof was already speeding out the factory gate-it was to be my shadow for five days. In it were the backfield that had been chosen to run the interference for this final play: Bob Labensky, the project engineer who had cast his lot with the penniless Sikorsky of nineteen years ago and had remained loyal through lean and rich alike; Ralph Alex, his assistant, who had labored endless days and nights to bring this craft to flying condition; Adolph Plenefisch, shop foreman on the helicopter ever since the first nerve-racking flights in 1939; and Ed Beatty, transportation chief, who elected to make this epic drive himself.

I quickly lost them in the elm tunnels of Stratford, but my maps were marked with the exact route they would take, so I followed it closely, always ready to land in some little field beside the road should the slightest thing seem wrong. They would see me as they drove by, and delays would be minimized.

Danbury was the halfway point on the first leg. It came in sight a little behind schedule. I was flying at 2,000 feet now, because the land was rising; and at that altitude there was a fifteen-mile head wind. Sixty miles an hour had been chosen as the best cruising air speed for the flight-easy onboth ship and pilot-and the head wind cut my true ground speed down to forty-five.

The day was getting hotter, and the oil had been slowly warming up until it approached the danger zone. It passed 80 degrees (centigrade) and crept on up toward 85. It worried me, and I watched it so closely that I didn’t realize until afterward that I was setting another one of those unofficial records-flying a helicopter across a state boundary for the first time.

Brewster, New York, drifted slowly behind and for a while my beacon was a winding ribbon of highway flanked on either side by almost unbroken forest. Finally, however, the open fields of the Hudson Valley caught my shadow like a giant whirling spider, and I began to let down for the landing at New Hackensack, just outside Poughkeepsie, thirty-five minutes behind schedule. It was pleasant to see George Lubben’s shock of red hair come bounding from the hangar as I hove in sight. Lubben was at this first stop to give the ship a thorough going-over, and, as I came in range of the field, he had been talking by phone with the ground party, who had gotten as far as Brewster and called to check progress.

On this first leg, besides the crossing of the state line, another record was written into our logbook: the national airline-distance record for this type of craft was unofficially established at fifty miles (since no other helicopter in the Western Hemisphere had flown any appreciable distance before).

From New Hackensack, I swung north toward Albany, flying about 1,000 feet above the valley floor. The mounting heat was building great white thunderheads above the Catskills, but they were still adolescent and presented me with only a modicum of turbulent air as I passed in front of them. Just below Albany, a few tremendous raindrops spread saucers on the windshield, but that was the worst those ominous clouds could do.

At the airport, I decided to land on the line with the other parked airplanes, nosing the ship practically against the fence. This was something that no other aircraft would ever consider doing, and everyone rushed from the buildings, expecting me to pile up among the automobiles in the parking lot. But the landing, of course, was without incident, and as I walked toward the hangars someone in the crowd grinned, “What are you trying to do-scare the hell out of us?” Another airline-distance record on this leg-seventy-eight miles.

From Albany to Utica was uneventful except for the pleasure of flying safely up the Mohawk Valley with the hills on either side often higher than the ship. I felt like the Wright brothers, looking down from my transparent perch two or three hundred feet above the housetop’s. Dooryards full of chickens and other farm animals would suddenly become uninhabited as hurried shelter was sought from this strange hawk-but the yard would quickly fill again as houses and barns ejected motley groups of human beings gaping skyward.

This trip was marked by constant astonishment, as people saw things happening in front of their eyes that they had never dreamed of before. This chronicle will be, in large measure, a report of their reactions and remarks.

At Utica I drifted up sideways in front of the hangar and hung there stationary for a minute or so while mouths dropped open wide enough to land in. Then I slid over to the ramp and squatted down. The guard greeted me as I walked up to the office: “I don’t believe what I saw just now! Of course, I realize this is a secret ship, but do you mind if I look again when you take off?”

Mr. Sikorsky’s World Endurance Record for helicopters was exceeded on this leg: I hour, 55 minutes. Also, another four miles were added to my previous airline-distance record, bringing it up to eighty-two miles.

If it hadn’t been for my constant concern over the mounting oil temperature, which now pushed close to 95 degrees centigrade, it would have been a beautiful flight from Utica to Syracuse. The sun was getting low in the west, the air was smooth, and a gentle tail wind puffed me into Syracuse Airport fifteen minutes ahead of schedule. As I hovered in front of the hangar where I thought we were going to house the ship, a guard burst around the corner to give me directions. His eyes popped open as he spread his jaws and his feet simultaneously, when he saw me awaiting instructions, fifteen feet up in the air! Recovered from his shock and reassured by my grin, he signaled me down to the other end of the field, and I could see apprehension oozing from the nape of his neck as he dogtrotted along the ramp with the helicopter’s nose a few feet behind and above him!

This first day had Lyone according to schedule. The helicopter had for the first time in history proved itself an airworthy vehicle, capable of rendering true transportation. It had traveled 260 miles in 5 hours, 10 minutes without even beginning to approach its high speed. However, a quick inspection of the ship revealed one difficulty in this particular craft that was to give us our share of worry in the weeks to come: the transmission was heating up badly. It seemed strange that we should create a totally novel aircraft and run into no particular structural, functional, or control problems -while a simple gear transmission, something that had been developed and used successfully in hundreds of millions of applications during the last half century, was destined to hound our every move.

When we started for Rochester the following morning, I kept the ground party and their yellow-spotted car in sight for several miles, but finally decided to cruise ahead at normal speed. It was another beautiful day, but the hot, calm air presaged thunderstorms.

At the outskirts of Rochester, I noted that the main highway went straight ahead into the business district, while a small cross-road led directly to the airport a few miles away. I lingered, debating whether or not to hover there until our car came along and signal them the best route to take, but finally decided that, in the interests of the overheating transmission, it would be best to go on to the port and check things over.

Above the field, I headed into the wind and slowly settled down facing the open hangar doors. Several men working inside “ran for their lives,” expecting a crash, but when they realized that there was no danger, they reappeared from behind airplane wings and packing boxes and watched the landing with unconcealed amazement. A guard came over and advised me to taxi up in front of the control tower at the other end of the hangar line. He didn’t realize, of course, that a short flight in this strange craft was much more satisfactory than taxiing on the ground, and he exhibited the usual reaction as I took off, still facing the hangar, and lazily buzzed along ten feet above the ramp.

The control tower was simply a square glassed-in box atop a fifty-foot skeleton tower at the edge of the operations area. No ship may land without first receiving a green-light signal from the control-tower operator. It was fortunate indeed that my ship could hang motionless in the air, because, when I whirred up in front of the tower and looked the operator in the face, he was so astounded that he completely neglected his duty and left me hovering there for the better part of a minute before he stopped rubbing his eyes. Then, with a broad grin, he flashed on the green light, and I settled to a landing at the base of the tower.

As I walked across the field, one of the instructors hailed me. “How do you expect us,” he asked, “to train our students? Here we spend months teaching them to keep plenty of speed at all times-and then you come along and make liars out of us with that crazy contraption.” (Confidentially, the next question that followed close upon this belligerent broadside was, “How soon can I get one of ’em?”)

The transmission was still running pretty hot, so we decided to fly to Buffalo with the metal cowling removed from the sides of the ship to try to get more air circulation. With a head wind and a promise of thunderstorms, I stuck close to the ground party so that if an intermediate landing were required they would be able to check the gear-case temperature immediately.

Down the highway we went together. I knew they were pushing along at good speed (they said later that it was often close to seventy-five miles an hour), and I was hoping a state trooper would pull them over, so I could hover just beyond his reach while he was bawling them out, or even giving them a ticket. No trooper showed up, however, so I had to content myself with flitting ahead to each cross-road to make sure there was no converging traffic to cause danger: then signaling them to proceed without worry at the intersection.

As we approached Batavia the sky to the west became darker, and an occasional streak of lightning sliced down through the black curtain a few miles away. I edged northerly for a time to see if I could get around the storm, but it was spreading across my path. It looked pretty good to the south, but I hesitated to get too far off course, particularly since I didn’t know what sort of conditions prevailed behind the storm front. So I finally decided to land and sit it out.

The car with its yellow dot had gotten itself misplaced somewhere in Batavia’s traffic, and I wasn’t sure which of two parallel roads it would follow toward Buffalo. So I leisurely swung back and forth between the two highways, trying to spot my earth-borne companions-keeping a weather eye on the progress of the storm in the meantime, and picking out a likely looking house with a telephone (I could see the lead-in lines from the road) where I could land and report my position. (Strange that with this aircraft neither the size of the available landing field, nor its surface conditions, had any influence on where to land, the only factors being a comfortable house and a telephone!)

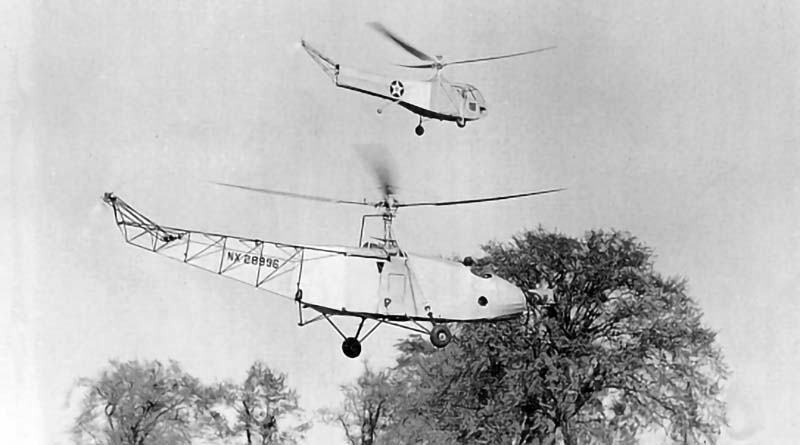

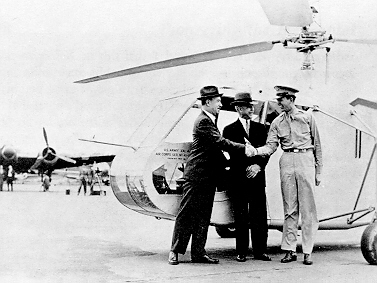

One of the first helicopter formation flights in history was made with Igor Sikorsky as pilot of the VS-300 and Les Morris flying the XR-4.

For reasons I cannot understand, I failed to pick up the yellow dot on the highway (they claimed I flew directly over them several times), and after five or ten minutes the storm was close at hand. I swung in over the spot I had chosen-a nice green strip of grass about seventy-five feet wide between two ploughed gardens. On one side of the gardens was a comfortable old farmhouse with its unpainted barns rambling out from under the big maples. At the other side of the gardens stood a shiny new bungalow that looked as though it might originally have been one of the cozy family group around the farmhouse, recently become independent and gone modern.

As I came to a stop twenty-five feet above the green turf, that old bugaboo lack of power became all too apparent. The engine just wasn’t able to cope with such unfavorable conditions as the calm humid air before a thunderstorm, and the “bottom” seemed to drop from under me. As the craft settled rapidly to earth, I spent a few uncomfortable seconds wondering about the safety of this experimental baby. Even here, the pilot’s safety was not in jeopardy, because of the ship’s unique abilities. The landing was a great deal harder than normal, but a quick check showed the machine to be unscathed by its experience.

The occupants of the house were only too glad to let me use their telephone. The owner-in his late seventies and on crutches-had been out in the chicken house when I settled in for the landing and was full of suggestions as to what had gone wrong with the engine, because he had heard it “sputter and backfire” when I came over. I don’t believe he ever became quite convinced that the landing was intentional.

The daughter lived with her husband and eleven-year-old girl in the new offshoot of the family mansion across the gardens. “Is there anything I can do?” she asked, as I approached. “Thanks very much,” I replied. “I hate to ask you to stay off your own property, but we are under strict orders to let no one near the ship. Would you mind just keeping people away while I telephone?”

“Willingly,” she said. So willingly in fact that, when Labensky and the others arrived during my absence, she firmly refused to let them pass until I had identified them.

After the storm was over and we were preparing to leave again, one of the people warned me quite persistently of a hidden ditch about 200 feet from the ship. I couldn’t make him believe that I would take off straight up, so I finally quieted his fears by assuring him, with thanks, that I would be careful. The ground party reported that after the take-off his astonishment knew no bounds-that the eleven-year-old girl gasped momentarily, but quickly recovered and jumped up and down shouting, “Boy! Will I have something to tell them in school tomorrow!”

Another storm was skirted before Buffalo, but finally the airport loomed out of the haze. The control-tower operator, I suppose, could not be expected to guess that the queer contrivance being visited upon him would not interfere in the slightest with an air liner that was about to land on the runway-so he gave me the red light. A short flight around the hangars brought me back to the tower a second time, and, although the air liner was still on the runway, the operator realized I saw him and flashed the green signal for landing. I settled in slowly over the buildings while a sea of faces gaped upward. I purposely overshot the edge of the ramp by twenty feet-then stopped and backed up onto it! The ground party, on hand for the landing, drifted through the crowd and heard: “I never thought I’d live to see one back up!” “I’ve given up drinking from now on!” “Well-now I’ve seen it all!”

One of the younger mechanics made the error of taking the story home to his family that night and gleefully reported the next day that his father, in all seriousness, said, “Son, I want you to give up aviation. When you start seeing things like that, it’s time to make a change!”

Owing to a long string of thunderstorms between Buffalo and Cleveland, we canceled out for the day and made arrangements to store the ship under guard.

The following day was not at all promising. Low clouds covered the lake shore, scattered showers were predicted, and there were head winds up to twenty miles an hour in the offing. We decided to take a shot at it, however, and got away late in the morning.

The usual weather prevailed in the pocket below Buffalo very smoky, hazy conditions cut visibility to less than a mile – but I steered my course half by compass and half by highway in order to be close to the road the ground party was following.

Once, as a towering radio mast loomed out of the murk, I was vividly impressed with the value of an aircraft that could come to a complete stop in mid-air if necessary. How comforting it was to know that I didn’t have to barge through this stuff at 80 to 100 miles an hour!

The lake shore finally came in view, and I followed it without incident to the government intermediate field at Dunkirk. The field was still wet from the storms of the night before, and the attendant was dumfounded when I hovered about until I found a high spot near the building where there were no puddles to step into.

The transmission was no better and no worse. I decided I could take one of the ground party on the next flight, and a flip of the coin chose Ralph Alex.

The weather was closing down so that, in any other aircraft, I would have been uneasy. Above us were low, nasty-looking clouds. Below were two parallel lines of puffy white ground fog that hung over the highways where the warm moist air from the pavements met the cooler air that was drifting in off the lake.

A few minutes after the take-off, we came on a bird about the size of a robin straying at our level. When he suddenly realized that an aerial meat grinder was fast bearing down on him, he fluttered a couple of times trying to decide which way to go-apparently couldn’t make up his mind-and finally in desperation folded his wings and plummeted for the ground.

It was on this flight, in the middle of a driving rainstorm, that a helicopter passenger was carried for the first time across a state line (New York-Pennsylvania).

At Erie, weather forecasts were bad: high winds, lake storms (I knew from past experience what they could be), very low clouds, intermittent fog. The low clouds and intermittent fog bothered us only because we would be breaking Federal regulations if we flew through them without complying with instrument flight procedures (which we could not do for want of a radio). But the high winds, upwards of thirty to thirty-five miles per hour, we were not yet prepared to face-particularly if they were bead winds as promised. So we stowed away at Erie for the night.

The next day we took off at noon in the face of a twenty to twenty-five-mile wind, because the forecast showed the probability of worse weather to come, which we might avoid if we got on to Cleveland.

A few minutes out of Erie, I realized that the transmission didn’t sound the way it should, and I could occasionally feel through the rudder pedals a kind of catching, as though small particles of solid matter were getting crushed in the gear teeth. After a few minutes, it seemed the best policy to land and confer with the ground party.

When they arrived, it was decided that Labensky would fly with me for a while to analyze the difficulty. If it were serious, we would land again-if not, we would proceed to our next scheduled stop: Perry, Ohio. It is significant that there never once entered into our deliberations the thought that we might not be able to find a suitable landing spot in case of trouble-with the helicopter, any tiny field was quite satisfactory.

For this whole flight, four ears were alert for untoward noises-and none appeared. Analysis some time later led us to believe that the extra passenger weight was sufficient to change the loading on the transmission so that it performed satisfactorily. Actually, however, it was slowly chewing itself to pieces and had to be replaced shortly after arrival at Dayton.

This was the roughest leg of the entire trip. The wind was gusty, varying from twelve to twenty-nine miles an hour. It was dead ahead, so I chose to fly low in order not to get into the stronger winds at higher altitudes which would slow us down even more. But close to the ground we got the full value of all ground “bumps.” Whenever I saw a ravine ahead, I would brace myself for the turbulence that was sure to be over it. Every patch of woods had its own air currents; and to the leeward of a town or village the air was very choppy indeed. Many times we lost 75 to loo feet of altitude in a down-gust-and we were only 300 feet above the ground most of the time. Once I watched the altimeter drop 180 of those precious 300 feet-and toward the end of the drop I began veering toward an open field, just in case it didn’t stop.

But the ship behaved beautifully. It didn’t pound and pitch like a conventional aircraft under similar conditions. All it did was float up and down and get kicked around sideways. There were no sudden shocks, and even when it yawed to one side or the other, it was not necessary to use the rudder to straighten it out-given a few seconds, it would come back by itself.

Labensky hadn’t bothered to get a seat cushion when he climbed aboard at my roadside landing place. For 1 hour, 25 minutes he had been cramped up on a hard metal seat with the circulation cut off from both legs. After we landed at Perry Airport, he crumpled out of the ship, for all the world like a newborn calf trying to walk for the first time!

There was no gas at Perry, but we still had enough in the tank to reach Willoughby, where we refueled for the flight into Cleveland.

Although the weather was a little better, this was a troublesome section, because I didn’t want to fly over congested areas quite yet. A long, sweeping circuit to the south carried me around the outskirts, and at last the Cleveland Airport loomed ahead. Somewhere down there, Mr. Sikorsky would be waiting. I learned later that he had picked me up with powerful binoculars eight miles away.

An air liner preceded me into the field, and I realized when I saw the green light from the control tower that they expected me to follow him in and land on the runway. But that was not the way of this craft; if I had landed out there, I would have had to take off again to get in to the hangars. My procedure was to fly down the hangar line until I. discovered the one where storage had been arranged and then land on the ramp in front of it.

As I meandered fifty feet above the hangars, the green light followed me. I could almost hear the fellow in the tower saying: “Get that – thing down!” He held the light until I drew close to the tower and then finally gave up. I hovered momentarily in front of him to see what he would do. He scratched his head-reached for the light again-thought better of it-and finally with both hands signaled me vigorously down!

I laughed and continued my perambulations. In front of one hangar there appeared to be more commotion than usual, so I headed that way. There was our crowd, Plenefisch and Walsh, and the hangar crew; and there, to one side, stood Mr. Sikorsky. He waved happily, and beamed with a broad, almost childish smile. A space had been cleared between the ships parked on the ramp, and I settled easily into it.

It was a thrill to shake hands again with Mr. Sikorsky. I wondered if the tears that flecked his cheeks were caused wholly by the wind.

The weatherman hadn’t been very hopeful about the conditions from Cleveland to Dayton, but it turned out to be an ideal Sunday morning, with a gentle breeze and high puffy clouds.

Mr. Sikorsky joined me on this part of the trip, and after hovering for a minute or two in front of the hangar at Cleveland, we turned and started south while the ground party in the car was still getting under way. When we were on course, I turned the controls over to Mr. Sikorsky. It seemed strange for me to be telling him anything about flying a helicopter, but his duties had kept him so occupied that he had handled the controls of this Army machine only once, for two or three minutes at the plant. He quickly caught the feel of it and from there to Mansfield I was simply navigator.

There was just one bit of advice that I repeatedly wanted to give him. He had learned to fly during the very early years of aviation, when everybody was reconciled to the fact that engine failure was synonymous with a crash-there was nothing you could do about it except rely on the resilience of the human body. On the other hand, I had been trained almost two decades later, when engine failures were still common enough to be a part of our daily diet, but something that we didn’t need to take so stoically if we would simply keep one eye constantly focused on a suitable emergency field. Therefore, on this flight from Cleveland, when a large patch of woods loomed up in front of us, and we were only a couple of hundred feet above the topmost branches, his instincts and mine were sharply at variance. He would fly happily over the middle of the patch without batting an eyelash, while I would be gazing longingly at the open fields a half mile to one side or the other where we could just as well have been, at the expense of an extra ten seconds. For the first time in my flying career, I began to realize that woods are not a solid mat of tangled branches, as they had always appeared from my respectful distance, but simply a group of individual trees with a surprisingly large number of relatively clear spaces between.

Nevertheless, the clear spaces still looked terribly small as I peered down and mentally tried to fit our aircraft into them. So after two or three particularly large wooded areas had somehow nuzzled their way below our wheels, I basely abused my role as navigator. Whenever I spotted a forest looming ahead, I would point toward the fields to the right or left and say, “We’re a little off course; we should be over there!” From the jagged route I made him follow, he must have thought me a highly incapable guide-but the remainder of the flight became very pleasant indeed!

Since he had never landed this ship, he handed the controls back to me as we approached Mansfield Airport. We landed close to the other ships, and he stepped out.

After a moment, he walked back. “Les,” he said, “how are you going to get the ship over to the gas pump?” I looked at the row of airplanes deployed between our craft and the pump and sensed his suggestion.

“Well,” I said, “if you will ask them to have someone hold the wings of the other ships, I’ll fly over.”

The clear space around the pump was about seventy-five feet square, and a quick jump was all that was necessary. His happiness flourished in the ejaculations of the bystanders.

I took off alone for Springfield, because we thought it best to have the ship as light as possible. It was the longest flight of the trip-ninety-two miles airline. Furthermore, the day had become quite warm, and we were not at all sure of what was going on inside the transmission.

The miles slipped by uneventfully, and in due course the Springfield Airport was below me. A small training ship had just landed as I came over the edge of the field, and he began to taxi toward the hangar at the far end, unaware of my presence. I kept just behind him about five feet above the ground as he bounced slowly along. When he reached the ramp, he turned to line up with the other ships, then suddenly slammed on the brakes and stopped dead in his tracks. The pilot said afterwards, “When I saw you, I didn’t know whether to open the door and bail out right there, or to give her the gun and try to take off over the wires!”

Before landing, I hovered a while, facing the incredulous group that emerged from the administration building. Then one young fellow signaled me very tentatively to move over slightly to the left. I obliged. With more confidence, he signaled me to the right, and once more I obeyed. With recklessness born of success, he signaled for me to go straight up in the air-and when I actually did so, he threw up his hands and quit! “That’s the biggest damn lie I ever saw!” he said.

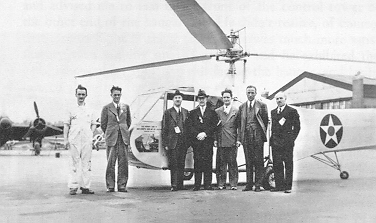

While I waited for Mr. Sikorsky and the others, an Army airplane from Wright Field circled the port. In it was Lieutenant Colonel Gregory, who deserves a great deal of credit along with our group for the creation of this craft. Hard work, ridicule, high hopes, and bitter disappointments had been his lot for years while he and his associates tried to bring into being just such a ship. Now, at long last, the proof of their courage and foresight was here.

Gregory and I impatiently awaited the arrival of the ground party. When they finally showed up, the side cowlings that had been removed from around the gear case, to give better cooling on the trip, were quickly buttoned on for the dress parade to Wright Field. Gregory phoned that we would be in at three-forty, the engine was started, and Mr. Sikorsky took his seat again beside me.

Off we hopped with Gregory not far behind in the Army airplane and Labensky just behind him in another ship hurriedly chartered at the airport.

In fifteen minutes Patterson Field was below us, and as we looked over the top of a low hill, Wright Field came into view.

“There it is!” shouted Mr. Sikorsky. His face twitched just a little’ and we exchanged another warm handclasp.

A couple of minutes later and we were circling the buildings. I couldn’t resist the temptation to zoom low over the ramp once, just to show that we had arrived. Then we circled back and hovered in the space that had been cleared for us a few feet in front of the operations office. Mr. Sikorsky waved joyfully to the sizable welcoming group that had gathered.

We landed on a red-topped gasoline pit surrounded by airplanes of every description from the mammoth B-19 bomber to the tiny little private airplanes that were being considered for various military missions, and Mr. Sikorsky stepped out, proud and happy at the successful completion of an epochal mission.

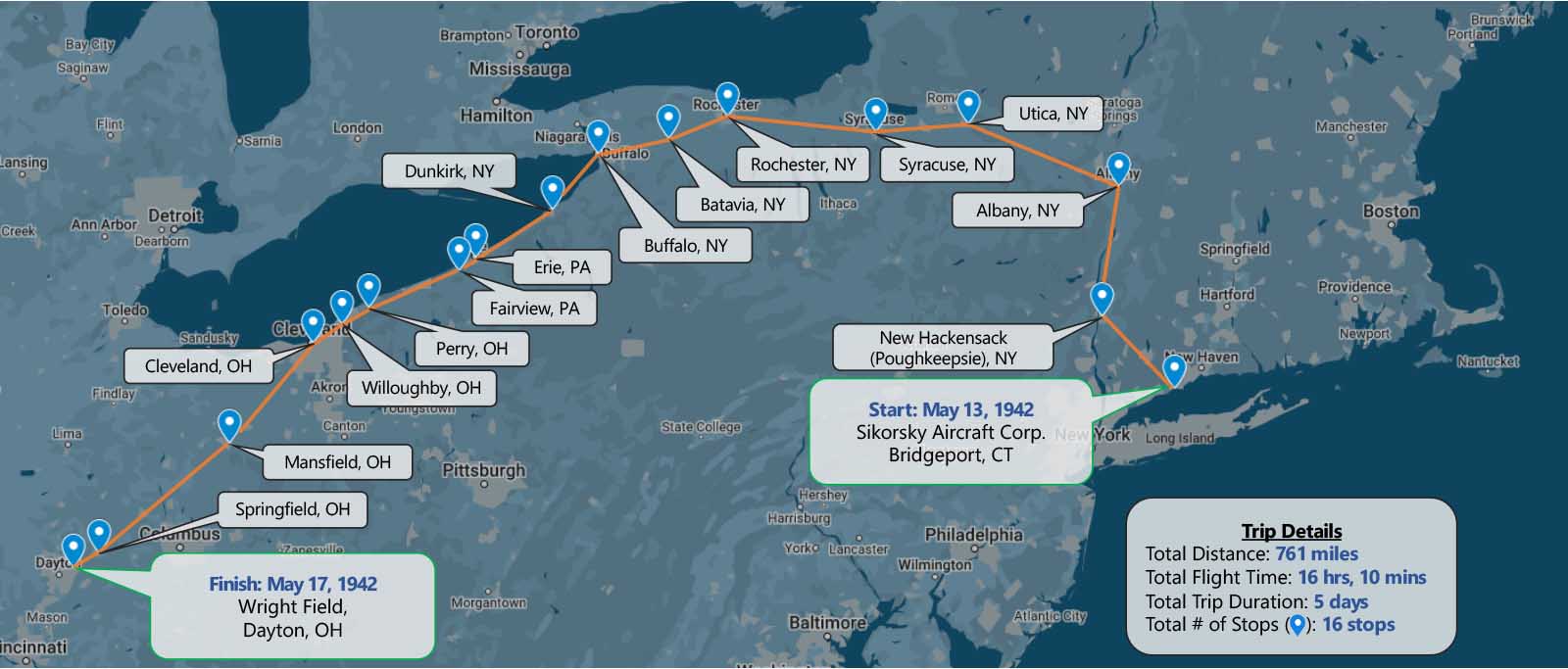

Recapitulation of facts regarding the XR-4 delivery flight: Five days elapsed time; 761 airline miles; 16 separate flights; 16 hours, 10 minutes actual flying time; four states covered; first helicopter delivery flight completed; unofficial American airline-distance record repeatedly established and exceeded, finally to remain at ninety-two airline miles; first interstate helicopter flights (unofficial); first interstate helicopter passenger flights (also unofficial); World Endurance Record for helicopters exceeded with a flight of 1 hour, 50 minutes (most regretfully unofficial).